Clarke Mackey, filmmaker-teacher-mentor-provocateur

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: June 7, 2016

“I’ve always believed that art is not an escape from reality, but it is one of the ways that we live with reality.”

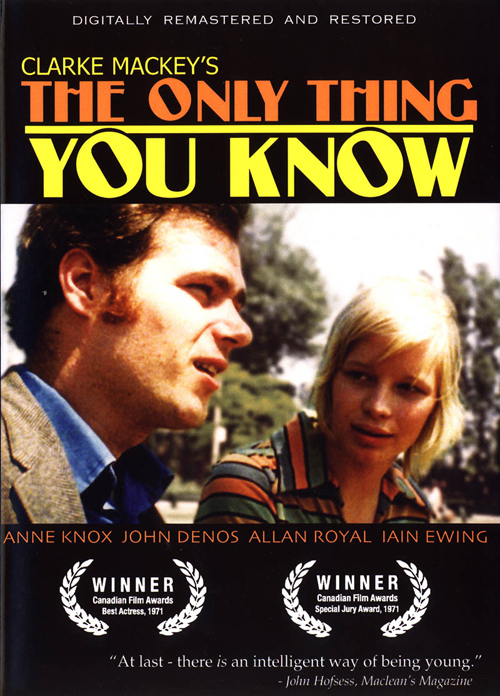

Of all the professors in the Queen’s University Department of Film Studies when I was a first-year student, Clarke Mackey was the one whose reputation most preceded him. He’d directed some of the first season of Degrassi Junior High, which I really liked, and had made a splash in his early film career with two features: The Only Thing You Know, which he made at age 19, and which won Best Actress and the Special Jury Prize at the 1971 Canadian Film Awards (now the Genie Awards); and Taking Care, which won the 1987 Canadian Film and Television Award (now the Gemini Awards) for Best Feature Production and was nominated for a 1988 Best Actress Genie Award.

I hadn’t seen any of Clarke’s movies when I first chose film as a concentration, but I knew that he seemed fun and approachable and that his Film 350 Production class was the one to try to get into. Since taking that class (and others he taught), having him as a thesis advisor for the script to my short film Sight Lines, and working with him as a teacher’s assistant, our connection has evolved from a student-teacher relationship to a true friendship. In the years since I graduated from Queen’s, he’s proven tremendously encouraging, supportive and helpful. He was understanding when I strayed from the film path, and he’s been enthusiastic about my returning to it, on whatever terms I choose.

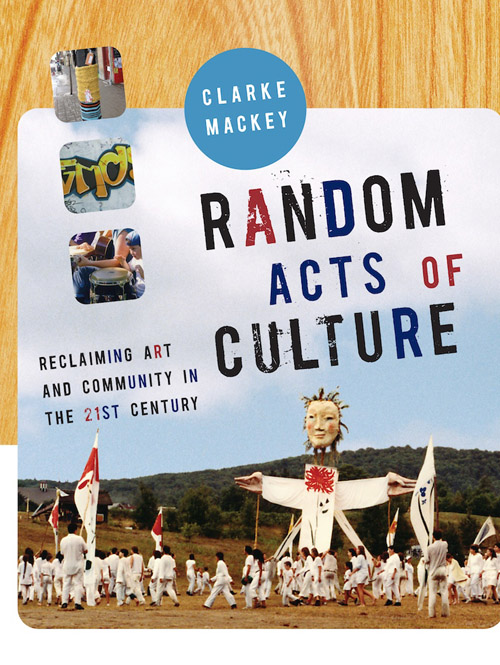

It’s not surprising that he encourages people to blaze their own trails. Throughout his life, he has done just that, from his unorthodox approach to filmmaking, to his 2010 book Random Acts of Culture, which explores his thoughts on vernacular culture and which, he says, “presents ideas that challenge much of the assumptions that drive the thinking about film.”

When Clarke began emerging on the Canadian film scene in the 1970s and 1980s, his work was met with critical acclaim and his name was tossed around with the likes of David Cronenberg, Claude Jutra and Don Shebib. But then he threw it all away, first to work in a daycare and later to teach undergraduate students. At least, that’s how some of his contemporaries in the film world have seen it.

Clarke has a different perspective.

Director’s cut

Ever since falling in love with film in the early 1960s, Clarke has been drawn to “alternative” productions. His interest was piqued by two films in particular: Don Owen’s Nobody Waved Goodbye and Claude Jutra’s À tout prendre. Both Canadian, they were collaborative efforts that featured improvisational performances and a documentary-like style. Clarke took one look at those films and knew, at age 13, that he wanted to be a filmmaker. But he didn’t hear the calling until he was exposed to what he calls “a kind of reality, a kind of roughness” in those two movies, because he wasn’t buying the American approach to filmmaking.

“I’ve never been excited by Hollywood,” he says. “I was attracted to Italian Neorealism, to the French New Wave. I’ve always been an alternative filmmaker or an ‘arts’ filmmaker.”

In Nobody Waved Goodbye and À tout prendre, Clarke saw the potential to capture “the closeness of life and art that is not present in so much cinema—cinema that is highly constructed and fictionalized… Because Canadian cinema is a poor cousin of American cinema, it’s always been an alternative cinema. It’s always been a cinema that challenges and rejects the assumptions of Hollywood, and is going for something that kind of bridges the gap between art and life. The best Canadian films do that, in one way or another.”

Growing up in Southern Ontario—first Port Colborne, then Bronte—Clarke was the eldest of four children. His father was a teacher, his mother an artist, and both strongly encouraged their children to express themselves creatively. By the time Clarke was 14, he’d made several short 8mm films. At age 15, he made his first 16mm film.

He juggled classes at George S. Henry Academy around his filmmaking until the end of Grade 11, when he decided enough was enough. “I didn’t get along well with my teachers,” he says. “I hated the whole idea that you had to do what you were told and that there was this kind of progression where you went to school, and then you went to university, and then you got a job and you got married and all of that stuff. I really rebelled against it. At that point, I was already very determined to be a filmmaker.”

Clarke quit school and, after a year of looking for freelance jobs in the film industry, found work in Toronto, Ontario as an assistant editor for the CBC. He spent the next two years synching rushes and getting what he considers to be his formal filmmaking education. “Because I was preparing the rushes for all the productions that were going through there, I basically saw how all the cameramen worked, how all the directors worked. I learned how to direct by watching people’s rushes.” He also volunteered to screen the rushes for film crews in the evenings, creating the opportunity to chat with camera operators and editors, who provided valuable insights into how not to direct.

In 1970, he left the CBC and set out to direct his first feature film, about a young woman’s self-discovery after leaving home. When The Only Thing You Know was released to great acclaim in 1971, doors opened for Clarke. He spent most of the next decade working as an editor, camera operator and director. He also got reacquainted with the formal education side of things; he took a pre-university course and then several undergraduate arts courses at the University of Toronto, and was hired to teach film at York University.

But by 1979, he found himself “questioning it all,” he says. “I’d achieved a certain amount of fame and I was getting work. But most of the work wasn’t that satisfying and it was incredibly difficult to make enough money to pay the rent. I also thought the industry was very commercial.”

“Clarke’s been an absolute inspiration in both his career and life choices. He was pivotal in encouraging me to think outside the box and helping to bridge from academia into the larger film industry, and I can only imagine how many other past students he’s helped to guide in similar ways. He continues to be a great mentor and friend, both professionally and personally.” —Kickass Canadian Alex Jansen, Owner/Operator, Pop Sandbox; Instructor for The Business of Media, Queen’s University Film and Media Department, 2011

Child’s play

Ever the idealist, Clarke began looking elsewhere for fulfillment. When an ex-girlfriend asked him to help with her sociology project by videotaping the children playing at Huron Playschool Co-operative, he agreed. As he writes in Random Acts of Culture, “The experience of visiting the school changed my life profoundly.” Watching children at play reminded him of how it felt to truly be in touch with one’s creativity and self-expression—not because it led to profit but because it felt good. He soon found himself at Huron Playschool Co-operative on a regular basis, first as a volunteer and later, at the parents’ request, as a teacher.

Over the next six years, he worked at several preschools and daycare centres, including Donvale Preschool (now Cabbagetown Co-operative Nursery School). He studied under Hélène Comay and Dorothy Medhurst, whom he calls “two of the most important nursery school teachers in Toronto.” Through working and talking with those women, he started to develop his ideas about vernacular culture—ideas that would form the basis not only of his 2010 book, but also of his future filmmaking career.

While working as a nursery school teacher, Clarke was able to fully satisfy his creative drive. Engaging in activities with the youngsters was creatively rewarding in and of itself; their proclivity for play and storytelling, in addition to arts and crafts, offered plenty of stimulation for the imagination. He also kept up his writing and music (guitar – acoustic; singing – bad yet joyful), and helped organize The Woods Music and Dance Camp in the 1980s.

But he was eventually “lured back into filmmaking as a way to make money.” In spite of the fact that he’d previously earned relatively little in film, “it was easier to make money in films than it was by teaching nursery school.” (That’s saying a lot.) So, he took a job editing a TVOntario (TVO) documentary about childrearing and the importance of play.

At first, he kept up his mornings at Donvale Preschool and spent his afternoons and evenings editing for TVO. Among many other projects with TVO producer Babs Church—a woman Clarke calls “just as idealistic as I was”—he directed the controversial 1983 documentary All Day Long, which challenged the notion that daycare is necessarily the best thing for every child. The film reignited his passion for directing, so he took on the 1985 drama Pulling Flowers, about the “hurried child,” who’s subjected to intense pressure by parents with high expectations.

As we talk about Pulling Flowers, Clarke comes down hard on parents who “rush” their children by using flashcards and sign language (for hearing children), saying it’s more about parental anxiety than about enabling expression in the child. “Kids don’t have any trouble expressing themselves. The evidence is overwhelming that children learn best in a situation where they’re given a lot of autonomy and they basically play. It’s the best form of learning because it’s directed by the child.”

With All Day Long and Pulling Flowers, he was once again hooked on directing. He left Donvale Preschool permanently and was “sucked back into the film industry.” But his next feature would quickly push him right back out.

Taking chance

In late 1985, Clarke read an article in The Globe and Mail about the Grange Inquiry into baby deaths at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). The newspaper included a statement from the Ontario Nurses’ Association (ONA), which said that the nurses were being blamed because they were “women at the bottom of a hierarchy,” he says. “I thought, ‘This is a movie.’”

One of the mothers at Donvale Preschool was a nurse, so Clarke approached her and she agreed to discuss the matter with him, as well as with his friend and screenwriter Rebecca Schechter, and a number of other nurses. Based on that brainstorming session, which was held at the mother’s home over several bottles of wine (“I’ll never forget that night,” he says. “It was an incredible night.”), Rebecca wrote the script for Taking Care. Babs and TVO backed the project—making it the first feature film to be supported by the broadcaster—Telefilm Canada contributed additional funding, and Clarke was back at the helm.

But although the film was well received, Clarke found the shooting to be “traumatic.” For one thing, the realistic style and collaborative approach he strove for had proved, “for a whole lot of reasons,” to be unattainable. His camera operator didn’t like shooting handheld. The actors wouldn’t perform without hair and makeup. Some of the cast took advantage of Clarke’s collaborative method to try to upstage the other actors. The result was a “very mainstream” product that went against everything Clarke believed in.

On top of that, Clarke’s son, Daniel, was born two months before shooting began, but the demands of filmmaking kept him from being present as a father and partner (he’d married Elaine Foreman the year before, after meeting her while she was assistant editor on David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone). Clarke wasn’t making enough money or time for his family, and when he factored in the huge disappointment of working on Taking Care, he knew it was time to pull out of the film business once again.

“Clarke taught me that acting like an irrational romantic is the sanest thing you can do to save what you love. And to never forget ‘they’ just want to know you can do the job and you’re a good person to go to lunch with. Both have been essential.” —Christopher Donaldson, Editor – Take This Waltz, Flashpoint, Being Erica (Queen’s Film Studies ’94)

Lessons learned

Clarke also knew that, if he wasn’t going to be directly in the film business, he wanted to teach film and that Queen’s was the only place he wanted to do it. In 1988, he applied for a two-year position at the university; when it was made into a tenure track position, he decided to give it a whirl anyway. He’s been with the Queen’s film program ever since, first as an associate professor, then as Department Head from 2005 to 2011.

“Coming to Queen’s was, in a sense, the absolute perfect thing for me,” he says. “I could still make the films I wanted to make, and I had much more freedom because I had financial security. I didn’t have to worry about feeding my family.”

A self-professed ham, Clarke loved having a captive audience in his students. He also brought many years of firsthand knowledge about the film industry and its technology, which he was eager to share. “I could teach the students how to record sound and operate the camera because I had done it.” Perhaps most importantly to the university’s upper echelons, he had been an avid reader, writer and thinker all his life, and fit right in with the program’s academic side.

“Clarke Mackey has gone above and beyond what he’s required to do as an educator. I consider him a mentor. He has truly inspired me to pursue a career in film and media, and pushed me to go beyond what I thought I was capable of doing.” —Grant Schelske (Queen’s Film and Media ’11)

Vernacular culture

Since joining the Queen’s faculty, Clarke has continued to produce an abundance of film and media projects (not to mention a second child—his daughter Annie, born in 1991). All of his artistic pursuits have revolved around the idea of vernacular culture, which he defines as “creative activities that take place outside of the consumer marketplace and the world of trained professionals.”

His third feature, Dance on the Edge, is an experimental documentary about post-modern celebrations that premiered at the 1996 Figueira da Foz International Film Festival in Portugal. His innovative documentary website, Memory Palace: Vernacular Culture in the Digital Age, which launched in 1997, was nominated for a WebSage Streamers Award and featured in Forbes magazine. Disrobing the Emperor: The New Commons in Mexico, a one-hour exercise in participatory video that he shot in 1998 and released in 2000, offers a window into the lives of people living in three self-structured “squatter” communities that operate outside the Mexican government’s system. With the 2003 short documentary Eyes in the Back of Your Head, he collaborated with former federal inmates to create a collection of still photographs that “tell stories and provoke controversy about justice and prison issues.”

“My first job on a feature film was to sound-edit Clarke’s documentary ‘Dance on the Edge,’ while still a student in the film program at Queen’s. Clarke recognized a path that might bring me success even before I recognized it. He put together a few of my demonstrated interests and skills and subtly guided me toward a career in sound. Almost 20 years later, I’m still following that path and have Clarke to thank for it.” —David McCallum, Supervising Sound Editor and Owner, Tattersall Sound & Picture (Queen’s Film Studies ’94)

Random Acts of Culture

One of Clarke’s most recent works is his first published book, Random Acts of Culture. As mentioned, the ideas behind the publication had been percolating in his mind and imagination for more than two decades. But he was apprehensive about exploring some of the thoughts that ran contrary to academic orthodoxy.

Eventually, though, when social and digital media made it clear that times really were a-changin’ (the Queen’s department itself had recently changed its name from Film Studies to Film and Media), he felt that the time was ripe for him to speak his mind. “YouTube and Vimeo… point to a new reality where the amateur is not so despised,” he says. “There is more of an openness to the creativity of ordinary people.”

Random Acts of Culture is all about celebrating the creative contributions of the many, the “ordinary,” rather than deifying virtuosos. Clarke goes back several centuries and looks across the globe to cite myriad examples of times when art was collaborative, and of how consumer culture shifted our mindset to one in which art is considered something to be created by “the talented few” and consumed by “the untalented many.”

“For the last 100 years, there seems to have been this progression—aided and abetted by the consumer culture we live in—towards (a line of thinking that) culture is a kind of product that’s for sale,” he says. “What I try to argue is that that is a distortion of how culture actually works. We’re all culture-makers; we’re always making culture, whether it’s the way we cook a dinner or the way that we dress or whatever. Culture is in the way that we talk to each. The professional/amateur divide is an artificial one and it’s created to make money.

“I think that somehow, people in the modern world are under some strange illusion that they’re individuals and they don’t need community; they just need a couple of friends, but we’re all these autonomous beings. When in fact we’re all deeply connected to each other and we need each other in all kinds of ways… (Art should provide) a sense of community and a sense of belonging. I’ve always believed that art is not an escape from reality, but it is one of the ways that we live with reality.”

“Clarke Mackey is the kind of professor who inspires the best in his students, past and present, not only in the world of film but in the world at large.” —Vicki Rivard (Queen’s Stage and Screen Studies ’04)

The art of inspiration

Clarke released his book in a whirlwind year, as he was heading into his last days as Head of the Queen’s Film and Media Department. He’s currently enjoying a one-year sabbatical, during which he has a number of projects on the go. He’s continuing to promote his book and is regularly blogging about vernacular culture. (Ideas for a sequel are already stewing.)

In addition, he’s shooting Revolution Begins at Home, a documentary about the time when his mother and two of his siblings became Maoists. And he’ll soon begin working on a video about the closing of Kingston’s prison farms, in collaboration with his wife Elaine and Queen’s Stage and Screen Studies graduate Lenny Epstein.

Come September 2012, Clarke will return to teaching as an associate professor in the Film and Media Department. He says that being around “all those 20-year-olds” keeps him young, or at least current. Through it all, he’ll continue creating films—on his own terms—and breeding a new generation of artists and filmmakers, who are inspired by his ideas, his teachings and his example.

* * *

To reach Clarke, email [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians