Neil Collishaw, driving force-Research Director at Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada

“… to get the body politic to move, scientific evidence is not enough… It needs to be buttressed by real human stories.”

In the 1970s, when Neil Collishaw started looking into the adverse affects of smoking, Canadians had no legislated protection from secondhand smoke. It took about 30 years of dedication, but since 2009, all Canadian municipalities have protected residents from smoke—at work and in enclosed public places. The thanks for this huge achievement go in no small part to Neil.

Currently Research Director at the non-profit group Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada, he has built his illustrious career working with a range of departments and organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Bureau of Tobacco Control and Biometrics. He’s made huge contributions toward protecting Canadians—and, in fact, the world—from the harmful effects of tobacco. Highlights include playing a pivotal role in developing and implementing the Tobacco Act; being instrumental in launching the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC); and accompanying the late Heather Crowe on her cross-country campaign to protect Canadians from secondhand smoke in the workplace.

His achievements and ongoing efforts have earned him many fans, including me. But one of his greatest admirers is his eldest daughter, Rachel Collishaw, a history and social science teacher at Ottawa, Ontario’s Glebe Collegiate Institute (GCI) who was quick to nominate her father as a Kickass Canadian as soon as she caught wind of my website.

“I really feel that he has made a huge and largely unsung contribution to reducing smoking in Canada and around the world,” says Rachel. “I think he’s absolutely a Kickass Canadian.” (For the record, Neil is just as impressed by Rachel: “I’m very proud of my daughter. She’s co-written a textbook called Social Science: An Introduction, and she’s constantly excited about her ideas for teaching history and for teaching people how to think.”)

The man behind the machine

Neil’s professional work with smoking may not have begun until the 1970s, but his first lesson in the dangers associated with the addiction came about 20 years earlier, when he was a youngster growing up in London, Ontario. His father, Edward (Ted) Collishaw, who had been a radar technician for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), decided to quit smoking cold turkey and pass on some words of wisdom to his eldest child. They were simple and to the point: “I don’t think people should smoke.”

“Like many of his soldier colleagues in World War II, my father took up smoking,” says Neil. “I think about three quarters of them smoked. But I think my father was distinguished by being about the first guy to quit smoking when he learned about the health hazards.”

As Neil tells it, the first scientific publications that spoke out against smoking—and were taken seriously—came out in the early 1950s. When word reached Ted in 1954, he put his cigarettes away for good, and did his best to ensure that his son would never pick one up. It worked. “Just that one little talk from my father seemed to convince me,” says Neil. “I never tried smoking.”

Smoke in mirrors

Unfortunately, not everyone followed in the footsteps of Neil or his father. Today, six million Canadian adults smoke, and they represent only about 0.5% of smokers worldwide. This is in spite of the fact that smoking—both firsthand and secondhand—is a known or suspected cause of more than 50 diseases or conditions, most of which are incurable and/or fatal.

When I ask Neil why he thinks so many people continue to smoke, in the face of such disturbing facts, he has this to say: “Since the very earliest days of health information coming to light from the early 1950s, the tobacco industry has been systematically and deliberately throwing sand in the gears, in various ways. They’ve been creating scientific doubt (as to the truth of whether or not smoking is harmful), where none exists. And to this day, they fudge on questions about the health hazards of smoking.” He cites the ongoing joint Blais and Létourneau class action suit against “the big three” tobacco companies as an example. “Tobacco industry executives get up one after the other and give evasive responses when they’re handling questions regarding the health hazards of tobacco.”

This kind of doubt, which extends to include dubious journals and studies that use “dodgy science” and report skewed results in favour of the tobacco industry, serves to feed the toxic cycle of smoking. “If you’re already a smoker, or are thinking of smoking, any sort of doubt like that is going to give you comfort,” he says. Add to that the fact that cigarettes are highly addictive (and that tobacco companies “monkey the cigarettes to ensure continued addiction”), and you have a pretty dangerous formula.

Neil points out that both the matters of supply and demand (and the ongoing demand push) need to be addressed in order to arrive at a sustainable solution to banning smoking. He mentions the possibility of regulating the structure of the tobacco industry, so that profit-negating penalties would be implemented if they sold more cigarettes from one year to the next. But even if Canada were somehow able to suddenly shut down all tobacco companies, he says, “you haven’t done anything about the six million addicts. Even though they want to quit, they want to smoke, too… We already have a problem with illicit drug use, but of the illicit drugs we have, we have nowhere near anything like six million daily or near-daily users, which is what we’ve got with tobacco.

“So while we (at Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada) are all for diminishing tobacco supply, you have to think carefully about it—about how you’re going to diminish both supply and demand, more or less in unison. We haven’t even started doing that.”

Lighting a spark

In spite of Neil’s obvious passion for improving world health, he didn’t set out to be a champion for anti-smoking, or other healthcare issues. After graduating London Central Collegiate Institute (now London Central Secondary School) in 1964, he pursued natural sciences, and then switched to social sciences. He completed a bachelor’s degree in sociology at the University of Western Ontario in 1968, followed by a three-term Masters in Sociology from the same school. But his first job out of university promptly landed him in the fields of health and medicine; he was hired in 1969 to document the admissions process at the Association of Canadian Medical Colleges (now the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada – AFMC).

A go-getter from the start, he easily zipped through his daily tasks. So the association’s then-Executive Director, the late Dr. Wendell MacLeod, encouraged Neil to read various social medicine books, in between reviewing medical school applications. “I was blessed by the fact that Wendell MacLeod was the ED,” says Neil, who names Wendell as a posthumous Kickass Canadian for his outstanding life’s work, which includes helping to establish the Montreal Society for the Protection of the People’s Health in the 1930s, and organizing several people’s clinics during the 1962 doctors’ strike in Saskatchewan (which earned him the title of Red Dean, as he was Dean of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan at the time).

With Wendell’s encouragement, Neil unknowingly laid the groundwork for his career. The social medicine books were “very much in keeping with my own training in sociology, about how structures work and how social structures determine things—and of course they’re a big determinant of health,” he says. “So, sort of in my spare time working at the association, I became very familiar with what seemed to me an important branch of sociology: social medicine.”

Thinking long-term

When Neil finished up at AFMC in 1971, he and his wife of three years, Barbara Collishaw (née Varty), embarked on a year of adventures that included studying French at the Paris Sorbonne University, and having their first of four children (Kevin, born 1972). After returning to Canada, Neil spent a few years working at Statistics Canada in Ottawa, before moving in 1974 to the former Department of National Health and Welfare’s Long Range Health Planning branch.

“Long Range Health Planning was a small group of smart people,” says Neil. “We’d sit around and think great thoughts and write papers, and they really made a difference.”

One of the group’s main products, which was nearly complete by the time Neil arrived, was a policy document called A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians. It was presented to the House of Commons by then-Minister Marc Lalonde, and “it really changed the direction that the health department was taking, and put very strong emphasis on primary prevention,” says Neil. “The (social medicine) reading I’d done under Wendell MacLeod’s urging really came alive, because we were finally going to implement it.”

In the seven years Neil spent with the branch, he was involved with many papers and initiatives aimed at incorporating primary prevention to reduce death and disease, from things like alcohol abuse, lack of exercise and smoking. “We looked at all the risk factors,” he says. “At the time, people were used to analyzing health problems in terms of diseases; there’s this much cancer, this much heart disease, and so on. We turned the whole perspective on its head and looked at health problems in terms of risk factors. It seems normal now, but it certainly wasn’t normal in 1974.

“I think we were instrumental in making it normal that people think hard about smoking and alcohol use and exercise and diet. These were, and are, the major risk factors that Canadians face, and they interact with each other and they cause multiple diseases. And they’re the ones that, at least in theory, you’re able to change. So if you want to work on health improvement, you’re going to go after major risk factors.”

The writing on the wall

Ultimately, Long Range Health Planning was cut, along with “all of the long-range planning outfits,” in the early 1980s. But not before Neil developed a solid understanding that, of all the risks they’d analyzed at the branch, “smoking was far and away the biggest risk. It was then, and it still is now, by far the biggest risk that Canadians face, and indeed people all around the world. It’s the biggest killer, in Canada and globally.”

As he explains, although the “smoking epidemic” is on the decline in Canada, it’s still a major cause for concern. “Today, around 20% of Canadian adults smoke. In the early 1960s, it was around 50%. So that sounds pretty good—until you look at the actual number of smokers, because of course the population has grown. In the 1960s, there were six million smokers. That number rose to seven million in the 1970s, and these days it’s at about six million again. So in 50 years, we’ve gone from six million to six million smokers. Our percentage is going down, but tobacco companies still get about as much money as they did 50 or 60 years ago.”

His point goes back to issues of tobacco supply and demand. So far, efforts toward reducing smoking have focused on reducing demand. But that’s an uphill battle when people are strong-armed into feeding their addiction by a hugely powerful industry that takes in around $400 billion in annual revenue. (Neil makes it clear that the profit-driven structure itself isn’t the inherent problem; but, he says, “if the purpose of your profit-making corporation is to deliver addictive poison that kills people, maybe that’s not so good.”)

Tobacco Act

With all this in mind, Neil left Long Range Health Planning with his well-founded belief in the dangers of smoking firmly formed, and moved to the department’s Bureau of Tobacco Control, and then on to its Environmental Health Directorate. As Chief, and then Head, of the Tobacco Products Unit, he was instrumental in preparing and defending legislation aimed at regulating the tobacco industry.

The law was adopted by parliament in 1988, and then immediately challenged by tobacco companies. In 1990, a Montreal court sided with the industry, but Neil again worked to help the government, this time in winning a reversal of the decision on appeal. In 1995, the decision was again reversed—in the Supreme Court of Canada and in favour of the tobacco companies.

The law was lost. But, says Neil, “it had been enforced for seven years, before the Supreme Court judgment. In that time, the world had really changed. The government couldn’t imagine going back to a state of having no tobacco regulation.”

The Tobacco Act was “quickly written up” and came into force in 1997, while he was working for the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland. Not surprisingly, the tobacco industry challenged the new act as well. By the time the case went to court, Neil had returned to Canada and was again enlisted to help the legal team defend the Act. When it reached the Supreme Court in 2000, it was favoured nine to zero, and remains in force today.

A global perspective

While at WHO from 1991 to 1999, Neil accomplished a great deal in health promotion, and the prevention of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use. Of his many achievements, he names one of the proudest to be setting the wheels in motion for the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, an international treaty on tobacco regulation. “In 1994, it wasn’t even on the radar screen,” he says. “Today, almost every country in the world is a member.”

Now, at Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada in Ottawa, he continues to be part of the Framework Convention Alliance, which is a global non-governmental coalition that’s involved as an official observer in tobacco treaty negotiations and management.

Heather Crowe

Neil’s work with Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada also includes a powerful contribution that yielded some of the most dramatic changes to smoking in our country—not only as far as new legislation, but also with regard to shifting public perception.

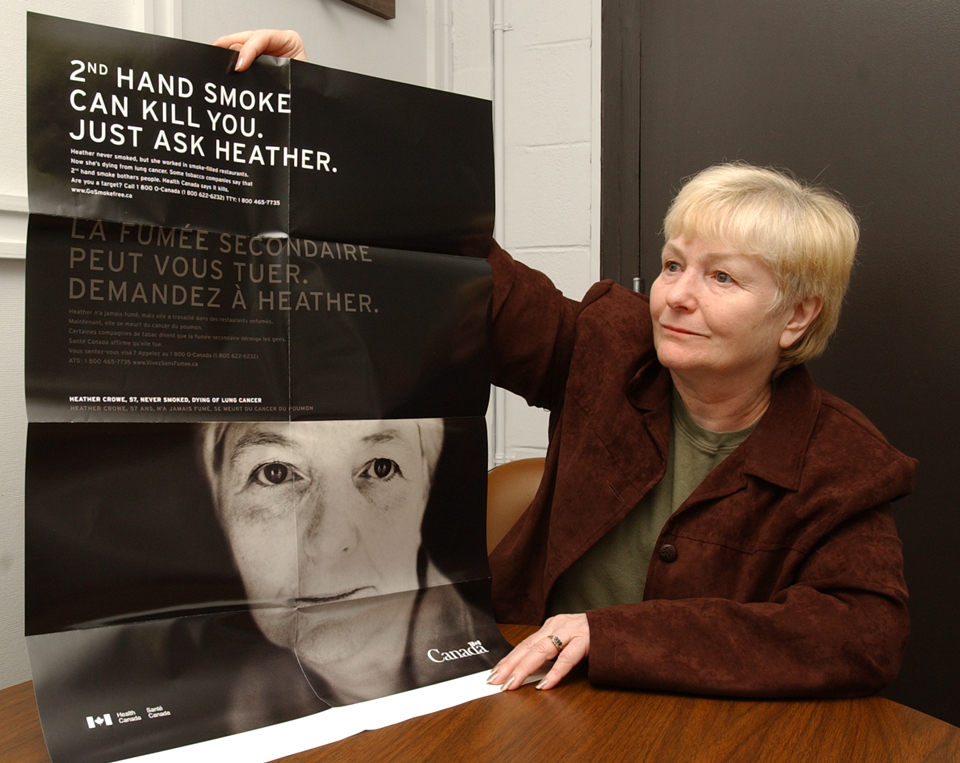

In 2002, Heather Crowe approached Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada. She announced that she was a lifelong non-smoker with lung cancer due to exposure to secondhand smoke in the workplace, and that she wanted to help protect other workers from the same fate. In response, the group made Heather their spokesperson for a national campaign in favour of controls on secondhand smoke.

Over the next couple years, while she received cancer treatment, Neil accompanied Heather across Canada. She travelled to nearly every province and territory in the country, speaking at city council meetings and talking with provincial representatives. “We just said, “Tell your story, Heather,’ and she would,” says Neil. “And her story was that she never smoked, but she worked her whole life in smoke-filled restaurants, and now she had lung cancer and she was going to die.”

Heather speaking at the Legislative Assembly of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta., March 2003

That “disarmingly simple” story packed a pretty solid punch. As Neil says, nearly everywhere Heather went, legislation soon followed. When he started working with Heather, only about 5% of Canadians had legislated protection from secondhand smoke at work. By the time she died in 2006, it was around 80%; by 2009, it was 100%.

“That’s no easy task,” says Neil. “For that to happen, laws have to change in every province, every territory and the federal government. I credit Heather herself, and Heather’s story, for motivating people to make that change. We’ve had scientific evidence in favour of such a policy since 1981. But to get the body politic to move, scientific evidence is not enough; it’s probably never enough. It needs to be buttressed by real human stories.”

Toward a resolution

Heather’s contribution, along with the work of Neil and his colleagues, has had a huge impact on the health of Canadians. Over the past dozen years, the number of youth picking up smoking each year has dropped from roughly 560,000 to approximately 260,000. And although the tobacco companies are still raking in money from selling about the same amount of cigarettes that they did 50 years ago, the percentage of Canadian smokers has dropped significantly.

Still, the costs for the toxic addiction remain frighteningly high. Tobacco-related illnesses leave Canada’s healthcare system with a bill of about $17 billion annually, and result in six million deaths worldwide each year.

To remedy the problem, says Neil, “we need to start thinking big.” In his mind, that means setting a firm date by which tobacco will be phased out, and standing by it. He points out that other countries are already moving in that direction. For example, New Zealand’s parliamentary committee recommended that tobacco be phased out by 2025, and Finland passed a law in favour of abolishing tobacco (although no date has yet been named).

He acknowledges that getting rid of tobacco will involve a careful balance of demand control and supply control measures—the latter of which he feels has been sorely neglected. “It really is time to start intervening on the supply side of the tobacco equation, if we want to make some serious progress against the tobacco epidemic,” he says. But, at the end of the day, “where we really want to get is to a point where nobody wants to smoke anymore.”

Neil has his work cut out for him. Although Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada is delivering outstanding work, they still have to fight for funding. With the 2012 budget in March, the federal government announced that it was cutting Health Canada’s contribution program component of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS), which had been a primary source of funding for Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada (as well as for many other non-profit, tobacco-control community groups across the country).

“When the government announced the cut, they said, ‘Well, we’ve made such good progress on controlling tobacco, we don’t need to do this anymore; the problem’s solved,’” says Neil. “But, like I said, we’ve gone from six million smokers to six million smokers in 50 years. Doesn’t sound like it’s solved to me. So hundreds of groups that had been getting contribution money, including us, no longer get any support from the federal government because the government has a wrong-headed view of what’s going on.”

With so many obstacles to overcome, keeping up the fight against tobacco is a daunting prospect. But even after so many decades in the field, Neil is still clearly fired up about protecting Canadians’ health and making our country smoke-free. When I ask what drives him to keep pursuing his quest, his own answer is disarmingly simple: “Well, it’s not fixed yet.”

* * *

For the latest on Canada’s progress against tobacco, check out smoke-free.ca. To reach Neil, email [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

The Environmental Protection Agency has concluded that secondhand smoke causes lung cancer in adults and greatly increases the risk of respiratory illnesses in children, and sudden infant death syndrome in infants. The carbon monoxide in tobacco smoke increases the chance of cardiovascular diseases, and children who breathe secondhand smoke are more likely to develop ear infections, allergies, bronchitis, pneumonia and asthma. Older children whose parents smoke get sick more often.

Thanks for the input, Saundra. Secondhand smoke is clearly a serious health hazard. I’m encouraged by Neil’s work, and efforts like the Running Room’s Run to Quit campaign.