Emily Wilson, philanthropist

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: December 19, 2013

“I feel a commitment and a responsibility to support other people in realizing their dreams and their visions, and in accessing basic services or having a voice—all these things that we have as Canadians.”

Wherever Emily Wilson travels—Canada, Zimbabwe, Nepal, Tasmania, Guyana—she plants a seed or a thought or a hope that continues to grow in all directions, even as she moves down another path. She seems driven, even destined, to make connections everywhere she goes. Once that connection is made, she carries the people and causes she’s discovered on to her next destination; the places she’s seen leave an indelible mark on her map, never letting her forget how they’ve made her better and how she can help to make them better.

Emily and I went to high school at Ottawa, Ontario’s Glebe Collegiate Institute (GCI), but I only knew of her at the time. I’d always had the impression that she was one of the real cool kids; that is, someone who’s actually cool (independent, unique, kind, giving) rather than someone who pretends to be “cool.” It wasn’t until my good friend (and inspiration) Sonia Wesche, another GCI alum, recommended Emily for this website that I discovered how right I’d been.

“Emily is a true humanitarian,” says Sonia. “Through her work, travels and day-to-day life, she is constantly connecting, engaging, empowering and brightening people’s lives. She never hesitates to dive in and take creative approaches to challenging social justice projects, whether they be local or halfway across the globe. She radiates positivity and strength.”

Sonia briefly brought me up to speed on some of Emily’s doings: her role as an Oxfam Program Officer for southern Africa; her involvement in the video Undermined that exposed the exploitation of indigenous peoples in Guyana by the Canadian mining industry, and which led to her being banned from the south American country; and her never-ending list of side projects to help improve living conditions for people around the world.

When I emailed Emily to ask her for an interview, she wrote back to ask for a donation for the book drive she’s currently organizing for the Edward Ndlovu Library in Gwanda, Zimbabwe. Then she sent me an article detailing her work with Pads4Girls; she got involved with Lunapad’s initiative by starting her own collection of disposable menstrual pads to bring to Zimbabwe in 2008, before approaching the Vancouver-based organization about supplying reusable organic cotton menstrual pads to the Sexual Rights Centre in Zimbabwe. To this day, Emily transports Lunapads’ donations whenever she travels to Africa. The article also outlined how she’d partnered with Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE) in 2009 to raise thousands of dollars so that Zimbabwean Mbonisi Zikhali could enroll in a Masters of Journalism at Carleton University. (He’ll graduate in 2012.)

Emily (far right) delivering Sanitary Wear donations to the Haven shelter in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

There seemed to be no end to the number of initiatives Emily had her hand in, and all for the greater good of those who’d been fortunate enough to cross her path. One of the first questions I jotted down for our interview was: What drives you and gives you the energy to do so much for others?

Spreading her wings

It turns out Emily’s mother was a big influence in her desire to “help people and support people and get involved in community activities.” After hearing Stephen Lewis talk about the plight of African grandmothers, whose many children had died of AIDS and left behind dozens of young grandchildren, Jennifer Wilson started up one of the first Ottawa chapters of Grandmothers to Grandmothers through the Stephen Lewis Foundation.

Emily also attributes her outgoing, and outreaching, nature to a shift that occurred after her beloved grandfather passed away. Irving Wilson moved from England to live with Emily’s family in Old Ottawa South when she was four years old. When he died 11 years later, she says she went into hibernation. When she emerged, “I kind of exploded onto the scene,” she says. “As my mom puts it, I metamorphosized.” Formerly quite shy, she became involved with students council, yearbook committee, grad committee, improv team and drama club. “I got more interested in building community and organizing things and working with other people.”

Getting un-lost

After graduating high school in 1996, university didn’t feel like the right direction for Emily; giving back and collaborating with others felt more like the path she wanted to be on. She put off post-secondary education, took a job at Loeb grocery store (now Metro), and began distributing pamphlets to raise money for a volunteer mission with Students Partnership Worldwide (now Restless Development). Once she’d raised and earned enough money, she headed to Zimbabwe in 1997, where she participated in the inaugural year of Restless Development’s environmental education volunteer program. She spent four months volunteering in the country, and another four months hitchhiking with a friend throughout the region.

It was in telling me about her first time in Zimbabwe that Emily gave me the meat of the answer to my question about what motivates her to do so much good. “That was a really life-changing experience,” she says. “It shattered my whole reality and worldview, and really made me think about things very differently. I’d never been immersed in other cultures in that way; I’d never seen poverty like that. It really fundamentally shifted how I perceived the world and my place in it and all the privilege I have… I think once you are aware of how much inequality there is in the world, and you see it and breathe it and taste it, and people you really care about are affected by it, you can’t not do anything.”

When she returned from Zimbabwe, she went straight into the International Development program at the University of Guelph. She’d wanted to stay in Africa and continue volunteering, but her parents insisted she take time out for a formal education. “Dad chose my school and my courses, because I really didn’t want to go,” she says. “But he made a great choice. I loved Guelph.”

Although she gave in to her parents’ wishes, she still made the university experience her own. She wasn’t fully satisfied with her program’s content, which “didn’t really look at any Canadian policy or Aboriginal issues; it was very much looking at ‘third world underdevelopment’ in isolation.” So she worked with her academic supervisor to develop her own degree, Cultural Identity and Community Development. In her third year of undergrad, she travelled to Australia, where she took Aboriginal Studies, and then spent four months exploring the country and volunteering on organic farms. She even had a stint as a beekeeper in Tasmania. After rounding out the trip in India and Nepal, teaching English on the Tibetan border, trekking the Everest trail and making a stop in Thailand, she returned to Guelph, where she finished her degree in 2001.

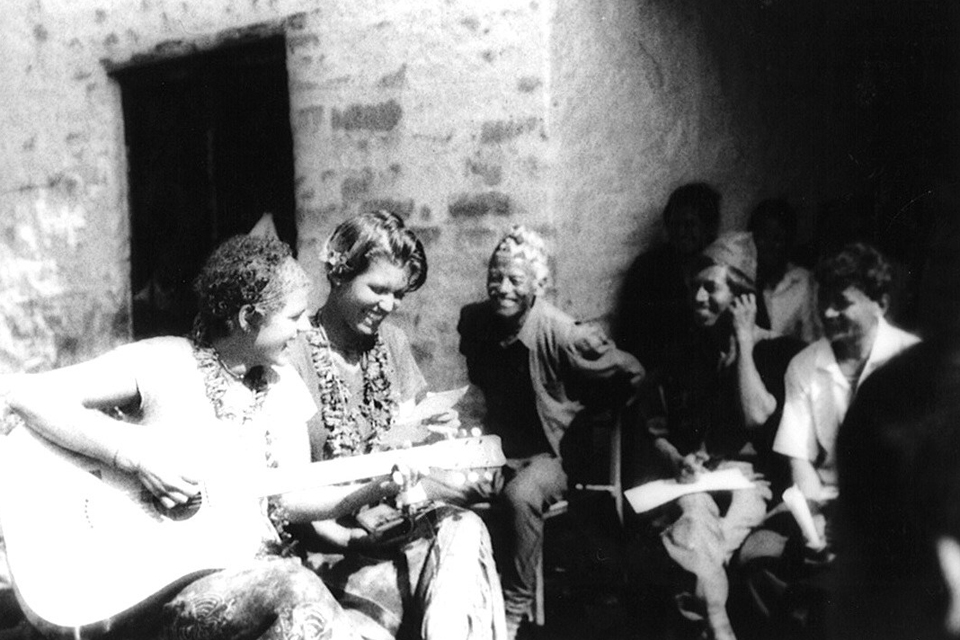

Emily (far left) singing a farewell song in Bulung Village, Nepal

Setting her compass

True to form, without a clear direction to channel her energies toward others, Emily felt lost upon graduation. Unsure what else to do, she took painting and landscaping work in Georgian Bay, Ontario, while she tried to decide whether to do development work in Canada or overseas. “Ethically, I felt I should be doing work in Canada,” she says. “But my heart told me I wanted to work overseas, because I really love learning about other cultures and challenging myself to work in completely different contexts.”

After landing jobs with both Katimavik and Youth Challenge International (YCI), she ultimately decided to focus her energies abroad. Through YCI, she travelled to Guyana, where she spent four months as a group leader for several Canadian and Australian volunteers in a remote community in the Amazon basin. Then, she and a friend biked to 22 indigenous communities to conduct interviews about local women’s concerns and priorities for a report on the need for a new community program in the region. The report resulted in secured funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) for a women’s rights and empowerment program that continues to run in Guyana.

Biking to Amerindian community in Guyana’s interior

Charting the next course

Emily was forced to return to Ottawa in 2003, when she caught a bad case of malaria. Once again, she found herself in a place where she wasn’t sure how to direct her energies to others. And once again, she felt lost.

But she’d come back with more than just an illness; she’d brought something to help find her way again. One of the community members she’d met during her first four months in Guyana shared her interest in spiritual landscapes. “On weekends, he would take me into the land,” she says. “We would hike together, and he would tell me all these stories about rivers and mountains and rocks and their spiritual inhabitants. When I left, he gave me a hand drawn map of all these places.”

Visiting a farm outside of Aishara Ton Village in Guyana’s interior

Upon her return home, Emily showed her father the map, and that pretty much sealed her fate as far as the next leg of her journey. A Carleton University theology professor, Stephen Wilson dreamt of bringing his daughter further into the world of academia. He encouraged her to show the map to a colleague of his who studied indigenous cartography. Emily agreed, and after a brief meeting with the professor, she decided to enroll in the Masters of Geography program and return to Guyana to conduct fieldwork in participatory mapping with local Amerindian women.

Emily (right) translating Wapichan terminology as part of her Masters studies

After completing her Masters in 2005, she took on a number of contracts, including one with The North-South Institute (NSI), for which she travelled to Guyana again to study indigenous perspectives on mining. Part of her work included helping to facilitate community workshops on mining and land rights issues.

“I had a video camera with me to film these leaders talking about the pros and cons of mining, so that I could bring it up to a Canada-wide consultation process on corporate social responsibility that was happening around that time,” she says. “(My work with the camera) sparked the idea within the community that they really wanted to make a film on the subject of mining.”

Undermined

The community’s interest was more than enough to light a fire under Emily. She went back to Canada and secured a public engagement grant from the Ontario Council for International Cooperation (OCIC). Then, she and fellow first-time Ottawa filmmaker Brent Parker headed to Guyana to shoot what would become a 35-minute documentary called Undermined.

“The main point of the film was to provide indigenous leaders with an opportunity to talk about problems they’d encountered with government or companies (throughout the mining process),” says Emily. “We were trying to frame the perspectives of indigenous leaders on what good consultation looks like to them, in terms of respecting them as people. They are totally left out of the equation. Decisions get made, and then sometimes a company might fly in and say ‘We’re here to consult,’ but really they’re there to tell them. There’s no option to say yes or no, there’s no option for negotiation. People are getting exploited.”

Emily shooting Undermined in Guyana’s interior

With production behind them, Emily and Brent returned to Ottawa and spent the following year teaching themselves to edit at SAW Video, a local co-op that had awarded them a post-production grant. While cutting Undermined, Emily began working for the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) on mining issues in Canada, and also put together an audio documentary called Bringing Birth Home. The doc focused on the movement among some Aboriginal communities in Canada to train local women in midwifery skills, including both traditional and western medical models, so that mothers can stay on the land for their births rather than being flown south to deliver.

Emily and Brent at the Undermined premiere in Ottawa, Ontario

Undermined premiered in January 2008 at Ottawa’s National Archives to an audience of 800, which included Guyana’s Minister of Amerindian Affairs, who was less than pleased with the film’s conclusions. Emily and Brent did their best to facilitate an open dialogue, inviting her to speak as part of the evening’s panel discussion with a range of international experts on issues such as resource extraction, indigenous rights, corporate accountability and public consultation. Despite Emily and Brent’s best intentions, the end result was a firm directive from Guyana’s Minister of Amerindian Affairs that they remake the film to include government perspectives on the issues, or consider themselves “persona non grata” in the country.

Emily (second from right) and Brent (far right) at the Undermined panel discussion

“Essentially, we were told we weren’t welcome in Guyana anymore,” says Emily. “It was quite an interesting experience and it blew me away. We didn’t make the film to be inflammatory. We weren’t pointing fingers; we wanted to engage companies and government into a discussion. The idea was to bring in this marginalized voice without offering an opinion on whether mining is good or bad, because there’s mixed opinions among the indigenous leaders and communities themselves.”

Out of Ottawa

The day after Undermined’s premiere, Emily landed her current job at Oxfam. Her experiences with the organization, both in Ottawa and throughout southern Africa, where she spends a good chunk of her time, have prompted her to launch countless volunteer initiatives. She nearly always has a bin on her front porch, waiting to be filled with donated items she’ll take with her on the next visit to Zimbabwe (case in point: the book drive). She also volunteers for the Canada-Mathare Education Trust, fundraising so that kids from the Mathare slum in Nairobi, Kenya can afford the tuition, uniforms and books necessary to attend secondary school. There are currently 38 students supported through the program, and the initiative is about to launch a similar program to get those students into post-secondary education.

Emily always finds ways of connecting people, at home and abroad, to improve the lives of those she meets. So it’s not surprising that what excites her most these days involves another connection: bringing her passion for video into Oxfam.

Throughout the editing process of Undermined, she struggled not because she was new to the technique, but because of its inherent unilateral nature. “The whole film is about consultation and giving people a voice, yet there I was in Ottawa in an editing studio deciding how the story was going to be told,” she says. “I started researching participating methods for doing video, and I discovered that there’s a whole methodology called participatory video, in which communities make their own films and can shape issues according to what they feel is important and should be depicted.”

Emily shares her knowledge with a young girl in Guyana

From the moment she made that discovery, Emily took action. For the last year, she’s been managing a pilot project in southern Africa that trains local facilitators who work with marginalized groups—including HIV positive women, sex workers and young women who aren’t in school—to use participatory video techniques. She also recently applied to the Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) for funding for a participatory video project to explore young Ottawa women’s views on feminism. “Participatory video is really exciting to me because it brings all these things I’m really passionate about together,” she says.

Making an art of giving back

Emily’s also yearning to further explore her own creative side, which hasn’t been easy given how many hours she spends working overtime and volunteering. “I used to perform a lot in Guelph; I’d write my own songs, play guitar and sing,” she says. “It was a big part of my identity, and it hasn’t been for awhile and I miss it. I feel like my life is so full a lot of the time that I just don’t have energy to bring it in.”

Rather than trying to create a new space in her life for art, she’s focusing on bringing her creativity into the spaces she’s already carved out; a sort of fellow traveller on her future journeys. “I want to link my passion for community activism and social justice, whether in Ottawa or overseas, with the arts and music,” she says. “That’s kind of what I’m exploring now.”

Through her various fundraising events, as well as her work in Africa, Emily is getting to know an increasing number of like-minded artists, including musicians, poets and dancers. “I’m trying to really understand the NGO world, and the music and arts industry, and help bridge those things so that people can be active and motivated to raise awareness in and about their own communities through the arts.”

She cites spoken word and hip-hop music as examples of potential tools for political and creative expression in southern Africa. “It’s such a vibrant community, and there’s so much going on that’s counter to what you read in the media here about Zimbabwe as this desperate place, which is one of the myths I’d like to help dispel,” she says. “Africa is not this dark continent full of poverty and kids with flies on their faces. It’s this beautiful, diverse, rich tapestry of cultures and languages and social movements and music and strength and resilience and laughter. One of my dreams is to make a documentary about the arts scene in Zimbabwe as a counter-story to the main narrative you get in media here.”

Finding the way home

When Emily talks about Africa with such passion and heart, it’s hard to know where she really feels most at home. In fact, she says, “I feel like I live in various worlds. I’ve got a foot planted in Canada and a foot planted in southern Africa, and Zimbabwe in particular. I live in two totally different realities, and maybe part of my motivation (for all of my work) is that I need to somehow make a link between those two realities.”

Lending a hand on the farms in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

“It’s been a process to get to a place where I’m okay with having a great life in Canada, and where I can enjoy my life here without feeling guilty about it. But I feel a commitment and a responsibility to support other people in realizing their dreams and their visions, and in accessing basic services or having a voice—all these things that we have as Canadians. There are definitely problems in Canada, and I also feel a responsibility to work to address some of those. I don’t ignore the fact that there’s poverty and homelessness and inequality and human rights violations in Canada as well. But in general, compared to a lot of places I’ve lived and travelled and worked, we have so much freedom here, and so much opportunity and so many privileges.”

On the map of Emily’s life, there are no borders. When she looks outside herself to see where she can help, she doesn’t stop at her front door; she doesn’t overlook what’s right beyond her stoop, either. Her world is a place where everyone is better off connected, and where people and communities take action to support, empower and inspire one another.

It’s a beautiful map, and one I can’t wait to see unfold even further.

* * *

To reach Emily, email [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Great article. Would love to reconnect with Emily one day to hear about her experiences firsthand. Love the web site. Always knew she was destined for amazing journeys.

Thanks a lot Jason! Well, now you have the means and a great reason to touch base with her… all the best!

You made a great choice in deciding to profile Emily. Emily is one of the greatest ‘movers and shakers’ that I have ever met. Aside from being an incredible person, she constantly finds ways to bring joy into the lives of those around her. Way to go Emily! You are amazing!

Thanks Sarada – I wholeheartedly agree!

Emily you continue to inspire. What a gift you are to this world!

Hey lady!! love it. Thanks for sharing your light in this world. Wow! so Bright. love p.

Wow! That’s about all I can say!

magnifique et inspirant. l’amour de la session de la guitare dans bulung village!

im proud of you

thanks everyone for taking the time to read the article, and for your lovely feedback! i continue to engage in this world in the ways that i do, because of the love, support and inspiration that i receive from those around me – so thanks to all of YOU! i hope that our paths continue to cross as we journey through this beautiful and complicated world. peace!

I am so honoured to have this fabulous woman be one of the nearest and dearest in my heart and my journey through life.

Sometimes I forget how blessed I am to be around someone like you who have so much light to share with the world. So, Kickass Canadian, know that it is a great privilege to be your colleague and friend.

Ever since I met Emily at UofG I knew that she would positively impact the lives of many people, including me! Her passion, intelligence, kindness and energy are inspiring. I’m very proud of you Emily!

Hello!! I’m interested in having a screening of Emily’s movie, Undermined, for an event we’re having in Vancouver about Guyana later in March. Do you know how I can get in contact with Emily or where can I get a copy of the documentary? Thanks so much!

Hi Olivia, Emily’s email is listed above, so you can drop her a line there. I’ve also passed on your message directly. Good luck with Undermined! I hope it works out.

Wow – so great to hear more of Emily’s story! Thanks for sharing, and hope to cross paths with you again soon Emily, you Kickass Canadian!