Ann-Marie MacDonald, writer-actor-creator-feminist

“As an artist you have to have authentic self and an authentic core, which is a channel for stories and for meaning.”

Photo: Guntar Kravis

In the 1960s, there lived a young Canadian girl whose vivid imagination took her to places far beyond the reaches of elementary school classrooms and their rigid rules. For her, the stories she spun were always “truer than what might or might not be happening at any given moment in the ‘real’ world.” (To borrow from one of Barbara Wersba’s beautiful children’s books, “Her dreams are more real than her waking…”)

Such tendencies made life challenging throughout the girl’s youth, particularly when teachers frowned on her “useless daydreaming.” But as an adult, her penchant for mental meandering has brought magic and genius into the world, through her many creations and performances.

Ann-Marie MacDonald is a renowned and celebrated author, playwright and actor. To date, she’s probably best known for her stunning debut novel, Fall On Your Knees, which was a 1996 Giller Prize finalist and official selection for Oprah’s Book Club. But she is also a Genie Award-nominated actor for I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987) and a Gemini-Award winning actor for Where the Spirit Lives (1989). Her play Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) won the 1990 Governor General’s Award for Drama, and her musical Anything That Moves won a 2000 Dora Mavor Moore Award.

Ann-Marie’s second novel, The Way the Crow Flies, was a 2003 Giller Prize finalist and official selection for NBC’s TODAY Book Club. She hosted CBC’s documentary series Life and Times for seven years, and currently hosts and narrates CBC’s Doc Zone. Her latest novel, Adult Onset, was released in September 2014 by Random House, to great critical acclaim.

I was bewitched by Fall On Your Knees when it first came out, and have followed Ann-Marie’s career ever since. If you’ve read her work, you know what a lyrical and poetic author she is. Even more than that, she seems to possess otherworldliness; from her three novels, there’s a strong sense of haunting, of past and present irrevocably intertwined, and of a great connection to the wisdom of the spirits.

Such a rich tapestry begs to be examined, down to its barest threads.

A rootless tree, an orchard invisible

Ann-Marie grew up as an air force kid. Her father was an officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), and she was born in Baden Sölingen, in the former West Germany. She spent her early years on RCAF Station, 4-Wing, before moving with her parents, two elder sisters and younger brother to Canada.

As is the case with most military families, the MacDonalds moved around a lot. They returned frequently to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, which Ann-Marie’s parents considered to be home. But for Ann-Marie herself, “the concept of a place you go back to was once removed for me,” she says.

Without a place to truly call home, she grew up with a sense of rootlessness, and that seems to have fed her ongoing quest to pull truth from memory; in her work, she continually returns to places past in search of answers for which questions may not have even been posed yet. Admittedly, her books are all highly autobiographical and revisit many of the same themes: self-acceptance, self-loathing, homosexuality, homophobia, child sexual abuse and incest. (Ann-Marie says she herself wasn’t sexually abused.) In hindsight, she goes so far as to say that the books are something of a trilogy, tracing different families’ lives but asking many of the same questions, starting in the 1880s and finally landing in the present.

“I think it’s a very recognizable analogy for many of us, the idea of the restless soul,” she says. “A ghost that cannot rest and keeps trying to finish something that it didn’t finish, find something out that it didn’t find out in life, so that it can finally rest.”

Ann-Marie’s recurring exploration of lives past made me ask whether she believes in past lives. (After all, Adult Onset opens with the line, “In the midway of this, our mortal life…”) Her answer is fascinating: “In a kind of clear-cut, life-for-life sense, probably not; I don’t think anything is really that simple. But I do believe we are all recycled with absolutely everyone and everything else, so yes, of course past particles—which is a different kind of thing than a past participle—I would say past particles for certain. And I also believe we have a soul and that we do have a collective soul, and that we do communicate across time and space as a result, and I think that’s just really pretty obvious when you look at how Earth and cosmos keeps everything churning around and turning it into something else.

“I’d love to think that I was literally a certain individual lock, stock and barrel in 1801 doing something really interesting and possibly heroic, but I have a sense it’s probably not that cut and dried. But I wonder about ancestral memory. I always loved the John Lennon line from one of his songs, ‘There’s nothing you can think that can’t be thought, there’s nothing you can sing that can’t be sung.’ All you need is love, actually… So I believe in life and that we’re all part of it—past, present and future; animal, vegetable and the entire periodic table.”

Personal and political

Connected though we all may be, there’s still plenty of room for strife and discord among us, particularly when change is afoot. Throughout her youth, Ann-Marie struggled with more than just a wandering mind; she fought against the knowledge, however deeply buried it may have been, that she was attracted to girls.

In her family, and in that time, homosexuality was unacceptable. So she kept her shameful secret through all her years at Ottawa, Ontario’s Colonel By Secondary School, and into her post-secondary studies, first for one year of arts and humanities at Carleton University, and then at the prestigious National Theatre School of Canada (NTS), from which she graduated in 1980.

From an early age, acting and writing offered Ann-Marie a means of escape from her inner turmoil, as well as a way of making sense of it all. “It was the drive to inhabit and be inhabited by stories that I felt I understood,” she says. “The most important thing in the world was to live through a story and to have the attention of other people. I was shy and socially awkward, but confident onstage, like a lot of people who end up as performers. I wouldn’t necessarily be the one standing in the kitchen at the party regaling people with hilarious anecdotes—I could never do that, I was never that person. But onstage I felt confident and happy; I felt at home there. I wanted to live through the story.”

After NTS, Ann-Marie moved to Toronto, Ontario, where she dove into the world of professional acting. During her first year in the business, she “auditioned for everything and did one of everything,” she says. “I did a television show, I did a feature film, I did a play. And then at the end of that year, I experienced a kind of depression because I had worked very hard, and I had enjoyed a lot of the things that I did and I felt very lucky to do them, but at the end of it, I felt like I had ticked some boxes and it turned out that I didn’t actually want what I thought I had wanted… So that was my first kind of crisis of identity, I suppose.”

Enmeshed in that crisis was the realization that she had to find out, once and for all, whether she was a lesbian. “I didn’t know who I was,” she says. “I didn’t want the things I thought I wanted; I wanted to want them because I thought they were within my grasp. I thought I wanted to be exclusively an actor and be straight and be the girl next door, so I was working my way through various ‘appropriate’ roles. But deep down I knew that wasn’t me… I thought, ‘I’m afraid I might be gay and isn’t that awful, but if this is true, I better go into it, I better find out who I am.’”

So she found the courage and self-awareness to come out, to herself and the world. Her parents’ reaction was a devastating rejection. (At one point her mother actually told her she would have preferred that Ann-Marie have cancer than be gay.) But her colleagues, and the artistic community at large, embraced her as she was.

“I came out and that’s when I also started doing feminist theatre,” says Ann-Marie. “I started making my own art and I became quite political, and that’s around the time that I started doing original work. So all of those things emerged at the same time, because as an artist you have to have authentic self and an authentic core, which is a channel for stories and for meaning. (In coming out), I actually discovered a larger context; I discovered a feminist context. My world opened up exponentially and I understood how important it is to stand up and be counted, and to find out what your times are made of, and where you fit socially, politically, historically, creatively in your time. That’s when I first understood that there is no such thing as a non-political story; everything is political.”

Writing history

After the great success of Fall On Your Knees and The Way the Crow Flies, Ann-Marie made another politicized choice; she stepped back from her writing career to focus largely on raising her two adopted daughters with wife Alisa Palmer, whom she married in 2003 and who is currently the Artistic Director of NTS’ English section. Their children are now 10 and 12, but being at home with them during the “toddler trenches” offered Ann-Marie many new perspectives.

“My standards have changed a lot since I became a mother,” she says. “I don’t expect or hope for the same things for my children that I expected of and hoped for myself, and that’s a major shift. I just want them to be able to make friends and keep friends, and connect with other people and connect with their lives, and to self-authorize their own happiness and not need to seek it outside of themselves or to seek external approval.”

Becoming a mother also forced Ann-Marie to examine her own internal life more closely than ever before, thanks to her daughters’ uncanny ability to hone in on unprocessed baggage. “If you haven’t dealt with aspects of your personal backstory, your children will find them,” she says.

For Ann-Marie, that baggage came in many shapes and sizes. Of course there was her family history, and her parents’ rejection of her as a lesbian, which she hadn’t fully explored in her writing (or her psyche). But there was also a more innate beast that needed to be tamed. And she did just that when she set to work on Adult Onset.

The acclaim and recognition she received for Fall On Your Knees was wonderful. But it also took away some of her previous motivation for creating; namely, proving herself to others. Having gracefully and utterly cleared that hurdle, she was left with the naked task of simply getting on with the work.

“I couldn’t externalize the negativity; I had no external enemy anymore,” she says. “There was nothing standing in my way, and of course that’s when you understand that your own worst enemy lives inside your own head. So, I was forced to come against not just my own worst critic but the destroyer within. That was really, really hard… That internal critic was pretty much laid bare by the time I came to Adult Onset, and I really wanted to write about what that was made of; you know, what are our own interior enemies made of? Let’s just get everybody to stand out from the bushes and look at all these supposed enemies. Who are they? Where do they come from? … It’s that dark voice that is authenticity, that says, ‘This is the way out.’”

From Fall On Your Knees:

“Her mother has warned her against gazing too long into a mirror. If you like too well what you see there, the devil will appear behind you. She smiles at herself. And gets stuck. Can’t move. Can’t look away or break the smile tightening to a grin on her face until she seems to be mocking herself. That’s when she sees him. In the shadows behind her. His smooth stuffed head. His hat. His no ears. His no face. She whimpers. He watches her, Hello there. She can’t find her voice, is this a dream?”

From The Way the Crow Flies:

“Here is something that will always make sense: it’s my fault.”

From Adult Onset:

“How do you tell yourself what you already know? If you have successfully avoided something, how do you know you have avoided it? Land mines of anger left over from a forgotten war, you step on one by chance. Sudden sinkholes of depression, you crawl back out. A weave of weeds obscures a mind-shaft but cannot break a fall, you get hurt this time. A booby-trapped terrain, it says, ‘Something happened here.’ Trenches overgrown but still visible from space, green welts, scars that tell a story.”

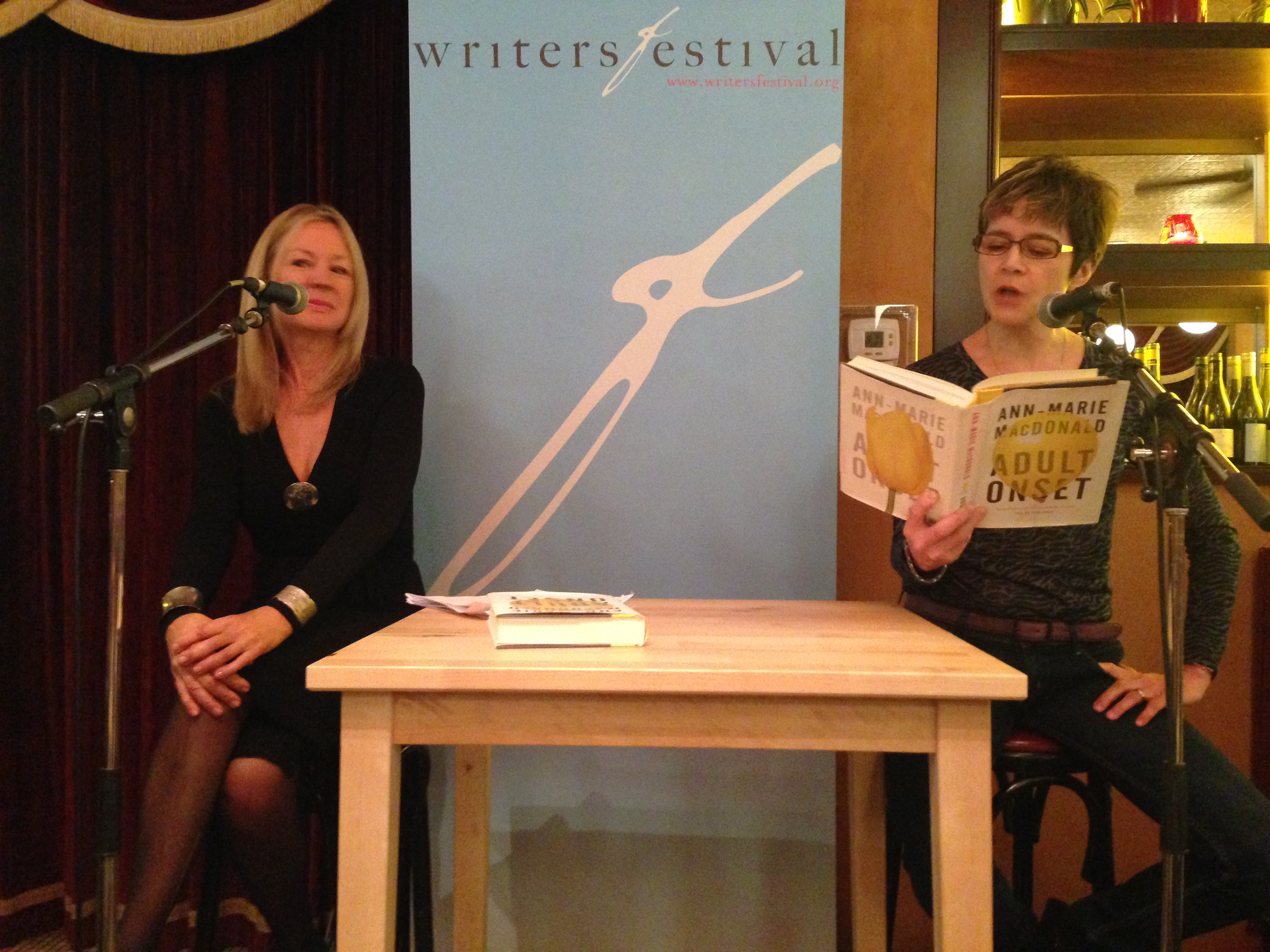

Ann-Marie (right) reading from ‘Adult Onset’ at the Ottawa International Writers Festival, with CBC’s Sandra Abma, November 2014

From darkness to white (space)

Given how deeply personal Adult Onset is, I ask Ann-Marie why she didn’t write the book in first person. “I did write it in first person,” she says. “I went back and forth and back and forth (between first and third person). At a certain point I did a huge global change of pronouns in order to get some more distance on it, in order to be able to see some more definite narrative outlines, you know, edges, and it really helped.”

Ultimately, she doesn’t know why she landed in third person. But beginning in first person is a practice she’s employed for all three of her novels. Whether consciously or not, it allows her to tap into her own darkness to find the ultimate truth of each story. And for all of them, that truth seems to be a tale of love overpowering evil. (From The Way the Crow Flies: “Love’s guilty secret: it doesn’t hurt…”)

“At a certain point when I was writing (Adult Onset), what rang most true to me (when describing darkness or depression) was the idea of an evil potion, an evil spell,” she says. “You imagine in the fairytale that you drink this potion and you’re transformed, and it seems always it’s only a completely selfless expression of love that can free you. Love that you had not earned, do not deserve and nothing about you would seem to indicate that you’re entitled to, and yet it is given to you.”

She recalls William Steig’s children’s book Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, about a young donkey who finds a magic pebble that transforms him into a rock, thanks to a wish gone awry. “He can only be freed if somebody will come and sit on that rock and say some loving thing about him,” says Ann-Marie. “Remember him, in other words; sit on the rock and remember him and then he’ll be free and come back to life. I think that’s really poignant and has a lot of meaning. I think sometimes all you can do is wait it out… In The Way the Crow Flies, in that dire scene, the mother is waiting for news of her missing child and it’s just, you know, ‘Stay still and the night will pass through you.’ It just will. Everything’s just going to keep going. That’s the law of physics; it’s all gonna change, it’s all changing all the time.”

On the more practical side, she also believes in “good manners and healthy habits” as a means of staving off darkness. For example, playing hockey, which she started doing after becoming a mom. “It definitely helped save me in so many ways,” she says. “I never, ever thought that anything as prosaic as a team sport would have such a profound impact on my life and soul and character, because I didn’t grow up with that kind of thing, and in fact I was one of those artists who was really snobby about team sports. I wore my loner status as a badge of honour. And now I go, ‘Wait a second, this is awesome! I’m friends with people I don’t work with! Who are these people called friends who are not also in theatre or writing books? Who are these people called friends? This is wonderful!’”

Life in general seems pretty wonderful for Ann-Marie these years. She made peace long ago with her parents, something she says came about through the passing of time: “They had to see me for who I am and accept that it won’t change.”

Even the formal education system has acknowledged and accepted her, after repeatedly trying to rein in her genius at an early age; in 2008, the University of Windsor awarded her an honorary doctorate of humanities.

She currently lives in Montreal with Alisa and their daughters. She’s working on a musical adaptation of Hamlet for the Stratford Festival, which is provisionally titled Hamlet: The Student Matinée. Alisa will direct, and Torquil Campbell of the band Stars is developing the songs. Ann-Marie also continues to host and narrate Doc Zone, currently in its final season. And she has her sights set on writing a Young Adult series further down the road—in a lovely spin on life imitating art, given that her protagonist in Adult Onset writes YA novels.

From the outside, it appears that Ann-Marie is constantly thinking and imagining, dropping metaphors as easily as others curse, and offering a steady stream of philosophies and insights. I can’t help but wonder what it’s really like on the inside; with such an impressive mind, is she ever able to turn it off?

“No” is her immediate reply, followed promptly by a characteristically analytical chaser: “Well, what do you even mean by that?”

In the end, Ann-Marie says this: “Believe me, I not only turn it off but I cultivate the ability to let it all go in a way that I used to do when I was a kid. I think that is a very, very important part of creativity, and I lost it when I grew up and started working really hard and getting a measure of success for my efforts. I actually rode roughshod over and barged into that huge space in my brain that used to just really be ‘good for nothing,’ and that’s the space, that’s the creative space that one needs. And that’s the space that I used to get in trouble for at school; that’s the daydreaming space, where I’m actually in a trance, I’m actually here and with a lovely kind of white space between my ears. That’s hard to recultivate when you’ve been a dutiful adult for so long, but I actually recultivate it by playing hockey, going for walks, meditating, all of those things, just doing physical tasks. I love physical tasks. I hate anything to do with a screen.”

That’s a funny statement coming from a writer in the digital age, particularly one who wants to keep writing. But she has a plan that will help her continue to create novels while minimizing her time gazing at pixels. “I need to waste more time, and I think that’s going to be the best thing that I can possibly do,” she says. “When it comes to writing, I’d like to spend less time staring at a screen and more time staring into space. I think a lot of us can benefit from that.”

So, she adventures back to that place where one’s brain assembles information from the past/present/future, and the subconscious chimes in to concoct a kaleidoscope of fantastic ideas. And so the young Canadian girl, who grew up to become one of the greatest Canadian writers, will continue to dream up stories that draw on our lives and reflect hidden truths. I can’t wait to read them.

(And once again from Barbara Wersba: “‘What colour are prayers?’ says a voice in her mind. ‘Dark… and gold.’”)

* * *

For the latest on Ann-Marie, visit annmariemacdonald.com and follow @AMMstuff on Twitter.

Thank you to Kickass Canadian Hannah Moscovitch for connecting me with Ann-Marie.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Thank you so much Amanda for this fascinating and graceful account of a very inspiring Canadian! Ann-Marie MacDonald is such a multi-talented artist and person, courageous in her honesty, and magical and transformative with her gifts. I look forward to her future work, as I have enjoyed and been moved by all that she has already accomplished.

Glad you enjoyed it! What a privilege it is to add one of my favourite authors to this site. 🙂

Ann-Marie, I am vice-president of the Algoma Fall Festival. Last night I saw/heard you and others at the Novel Dinner in Sault Ste. Marie. You are brilliant, authentic and inspiring. The evening, to me, had a “My Dinner with Andre” feel. It really didn’t need an audience to happen. My son is Adam Proulx who is a musical theatre actor singer and and writer (“12 Angry Puppets”) in Toronto. I understand him so much more in terms of the writing experience and the actual risks involved with the dig down process of creating a new work. Your conversations last night would make a great writers handbook. Thank you, Brien Proulx