Cynthia Bland, survivor-steward of children-founder of Voice Found

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: June 6, 2016

“I’ve come to a place where I would rather put my energy towards moving past what happened and really focus on the good I can do now.”

“I am no famous ‘star’ or celebrity but rather a person who is committed to using her voice to help others find and use theirs—and to keep children safe.”

Those words were part of Cynthia Bland’s email to me when she nominated herself as a Kickass Canadian. As I told her, I don’t normally take self-nominations; this website is devoted to people who inspire others. But in this case, it was more than appropriate that she nominated herself—it was important and empowered. So, I made an exception.

Because Cynthia is exceptional. She’s a successful sales, marketing and education consultant. She’s a mother of four. She overcame a cocaine addiction while raising her two eldest children on her own and holding down a steady job. She’s done all that and more, without even a high school diploma, working her way up through sheer grit and determination.

Cynthia is also founder and president of Voice Found, a non-profit organization committed to preventing child sexual abuse and supporting the healing of adult survivors. She started Voice Found because she understands firsthand the devastating effects of child sexual abuse; she was continually assaulted by an adult male neighbour when she was between the ages of five and seven, then by a gang of teen boys when she was 12, and again by a 21-year-old when she was 16. She kept all of that a secret until she was 47.

For decades, Cynthia struggled with self-loathing, panic attacks and a deep-rooted belief that she didn’t belong—that she wasn’t good enough. Profoundly disconnected from herself, she turned to drugs and alcohol, dropped out of school and treated her body, and her spirit, with the same lack of regard her abusers had shown her.

Throughout most of her life, she couldn’t even meet her gaze in the mirror. “I would look at myself and do my hair, do my makeup, but I never could make eye contact with myself,” she says. “I could never really look at myself in the mirror. It was always as if I were seeing another person.”

For Cynthia to nominate herself as a Kickass Canadian spoke volumes to me. I had absolutely no hesitation in breaking my “rule” and adding her to this site. In fact, it’s my honour to give her a platform for her newfound voice.

True stories

“Sometimes it can be difficult to talk about the abuse,” says Cynthia. “I kind of disassociate from it, I tell the story as if it happened to someone else. But sometimes I’m not that good at it and I’ll cry.”

Her story doesn’t start out sadly (and I can tell you now that it doesn’t end sadly, either; she was determined of that). She and her younger brother, Mark, grew up in Ottawa, Ontario in what she calls “a normal middle-class family.” Their mother worked at Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), their father was a musician and music teacher. Sunday mornings were spent at church, and Sunday dinners with grandparents, uncles and aunts.

“I had a happy childhood,” says Cynthia. “I always think back fondly to the early 60s, when women wore those beautiful Jackie O dresses. It was like an episode of Mad Men.”

Her parents were quite social, and with two young children, that meant hiring a babysitter from time to time. When Cynthia was five years old, and Mark two, their parents started turning to a man who lived next door and had made a positive impression as a standup, trustworthy neighbour.

“That’s when the abuse started,” she says. “He would come into my bedroom at night –” She starts to describe the specifics, but then stops herself. “I think it’s just more important to know that he abused me.”

What she does want people to know is that, like many serial abusers, hers didn’t start out with a violent act. “If they’re around and they want to have you in their life, they won’t begin with something intrusive. They really do a very good job of grooming you and making you feel that it’s a big secret between you… (My perpetrator) said, ‘You can’t tell anybody, you can’t say anything to anybody because you’ll be in trouble because your parents won’t understand what you did.’ They make it sound like it’s something that you’ve done. When I think back now, at the time I had no idea, but I’ve gone back there a lot of times and there’s no way I was the first person he assaulted. He knew what he was doing.”

Cynthia’s parents, however, had no idea. And so, it continued. “Because he lived in the neighbourhood, he had access whenever he wanted,” she says. “We lived next to a meadow and some woods. Quite frequently that’s where I would go out to play and of course he would come along and a lot of abuse happened outside in the woods.”

At first, young Cynthia found it confusing. “I remember thinking it was really weird. I had no frame of reference… And this is something that I think people forget about: sexual touch feels good. At that age, you don’t even know what it is, so you don’t really understand what’s happening to you.”

The initial, less physically invasive abuse was damaging enough. But after about a year of “normalizing” his behaviour, her abuser took things to a whole other level.

“When I was six was when it really got bad. As soon as he knew he had my trust, it got more aggressive. And that’s when he threatened that he would hurt my brother if I told anyone. And that’s where all the shame comes in. You know? I thought, ‘This is really not great, but I haven’t said anything and I’ve been a part of this, and I can’t say anything now because I don’t want him to hurt my brother. So basically, I’m just going to suck it up.’” At six years old.

Mark and Cynthia, aged 2 and 5

Gone but not forgotten

Eventually, Cynthia’s family moved and the abuse finally stopped. So, life carried on as usual. Seven-year-old Cynthia skipped to school, imagining a girlfriend hopping along beside her. She learned to write cursive and round off numbers. And when the other children played together at recess, she stood at the edge of the grounds, watching from afar.

“That’s something that’s repeated itself throughout my life,” she says. “Always being on the periphery and looking at others having fun and just not feeling like I belonged, at all… That’s not to say that I was always antisocial or anything, I mean I certainly did play with the kids in the neighbourhood. But more often than not, I would just remove myself and stand outside of the circle.”

She recalls an elementary school teacher approaching her and asking why she wasn’t playing with her classmates. Cynthia said, “I don’t belong with the other children,” which she now sees as a strong signal that something was wrong—but only detectable to adults who know what to watch for.

In addition to feeling like an outsider, she started suffering from panic attacks. She recounts an incident when she was eight years old, at a restaurant with her parents. “All of a sudden I felt like I was going to die and I needed to get out of there right away. I had to get out of there and it was the scariest feeling ever… These panic attacks would just start happening at random. They got really, really bad, actually, later on in life, super-bad. I didn’t know what they were, I just felt like I had these episodes where I felt like I needed to get away from myself really fast or I was going to die. But I couldn’t get away from myself and I couldn’t get away from the feelings.”

From left: Cynthia, a friend and Mark, Ottawa, Ont., 1964

Deeper into the woods

When Cynthia was 11, her parents divorced, something that was all the more difficult to deal with because of how rare it was back in the 60s. Still, she continued to hold things together remarkably well, at least on paper. She was placed in a gifted class for Grades 7 and 8, which she spent at W.E. Gowling Public School. But although her mind was thriving, her mindset was dangerously stilted, leaving her vulnerable and without the necessary tools to respond to threats around her.

When she was 12, she was assaulted by a group of five teenage boys, two of whom raped her. She had been walking along the bike path near her Carlington home, in a wooded area. She became aware that the boys were following her but, she says, “I didn’t realize what the heck was going on, or I did and didn’t do anything about it. Next thing you know, I’m pulled off the path into a more heavily wooded area and these boys thought it was really quite fun to taunt me and tease me. I remember them taking my top off.”

Things escalated from there. It was broad daylight.

I ask Cynthia why she felt she couldn’t report this assault—a blatant, violent attack by offenders who hadn’t been grooming her. “I think I always just felt like it was all my fault and that’s what I was kind of designed for,” she says. “I had such a sick, twisted self-image… I don’t usually talk about that assault when I was 12; I guess I just think it’s enough that anything ever happened when I was younger. It’s weird how I look at it. (When the rapes in the woods happened), it was kind of like, ‘Oh yeah, here we go again.’ It’s really sick but that’s how I look at it sometimes, which is not healthy. I’m still doing a lot of work just trying to reconnect with myself, because I’ve had to disconnect from myself so much, my head from the rest of me.”

One of the ways she disconnected was through drugs. She started smoking marijuana in Grade 7, then added cigarettes and alcohol to the mix, and was, in her words, “a full-blown party girl” by Grade 8. When she enrolled at Merivale High School, she also became extremely promiscuous. “That’s what I felt I was—a sexual object.”

She was thrown another curve when her father, who was remarried and had a new baby, moved to New Zealand. Cynthia had been living with her father and was besotted with her new baby brother, Matthew. She was devastated by their departure. At 14, she went back to live with her mother, brother, stepfather and three stepsiblings. “After that I only saw my dad every few years. So, I was dealing with abandonment as well.”

As if she hadn’t been through enough, she was date-raped at 16 by a 21-year-old man.

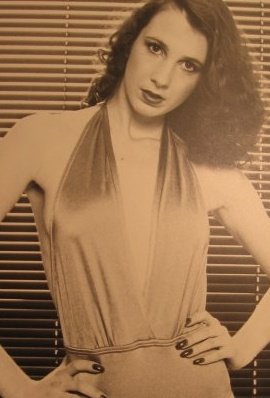

At 17, she’d graduated from pot to cocaine, but not from high school. She dropped out in Grade 12, left home and started working full-time in retail. She managed a chain of clothing stores, modelled on the side and had absolutely no trouble feeding her drug addiction. “I was really hot!” she says, before trying to retract her words, out of embarrassment. Delightfully, she finds the confidence to keep speaking her truth. “I was smokin’ hot, okay? This was in the 70s, and I was rocking a 36-22-35-inch figure, I was 5’7”, long wavy hair, I could dance like nobody else. Guys would give me anything. I never paid for a drink. The drugs were there, they were available. And it was my escape and it was a part of the scene. In the late 70s, early 80s, there was a lot of coke flying around. Combine that with being in the fashion industry and being desirable, I was very promiscuous. It was just a crazy lifestyle.”

But abuse drugs as she might, there was no real substance in that lifestyle for her to cling to. “It was just this excessive, crazy feeling, like I needed to be accepted but yet wanted to escape. I equated sex with love. I think I sought men out because I needed validation that I was important, that I was worthy, that I was something. It’s really kind of sad. I just look at so much of all that as just this big empty vacantness.”

Cynthia in 1979

Breaking patterns

In 1983, Cynthia married her first husband. On the surface, they were a “golden couple.” She was beautiful and successful, he was “the top model in Ottawa” and studying towards becoming an industrial psychologist. Below the surface, they were heavily into cocaine and living an unsustainable lifestyle.

Cynthia quit cold turkey when she became pregnant with their first son, Adam, but her then-husband never stopped using, and once their child was born, she found out just how hard old habits die. “I started living this double life,” she says. “I was like the perfect mom during the day, and then I’d put my child to bed and I’d start doing coke. It was really twisted.”

She repeated the cycle when she got pregnant again, stopping the drugs only until after her son Brandon was born. And then things got worse. “My ex was emotionally abusive, but then it went from emotional to physical abuse. There was one instance in particular that pushed it over the edge. We had been fighting and he had me over the couch and he had his hands on my neck, he was choking me, when our then-three-year-old came down the stairs and saw that. That somehow triggered my ex to stop, but I swear if Brandon hadn’t come down the stairs at that time, I don’t think I’d be alive.”

The incident was a major turning point for Cynthia. After eight years of marriage, she got a separation agreement, got out of the house and “never looked back.” Determined to make a better life for herself and her sons, she found work at Central Park Lodge Retirement Residence.

She also gave up drugs. “I stopped using altogether and it was not easy. I had my sons to look after and didn’t have the luxury of being able to take time away from work to focus on rehab. I just had to dig in.”

Going clean triggered a return of her panic attacks, so she found a way to see a psychologist twice a week. But there simply wasn’t time to be admitted to The Royal’s in-patient treatment program, which her therapist recommended. With no other guardian in her sons’ lives, she was determined to be there for them.

From left: Cynthia, Brandon and Adam, Ottawa, Ont., 2010 Photo: Shirley Bittner

Unlocking the truth

In the early 90s, things were starting to turn around for Cynthia. Ten years after her first marriage, she wed her second husband, Ian, a wonderful man she’d met while working at Central Park Lodge. A recovering alcoholic as well as a devoted grandson to his ailing grandfather, Cynthia says she was drawn to Ian because he was committed to a sober lifestyle and because they could be honest with each other about their “crazy, wild antics and addictions.”

In 1994, she gave birth to fraternal twin girls. (She also quit smoking, for good.) After a few wonderful years at home with her four children, she returned to the paid workforce, taking a sales job in high tech.

Things were “kicking along really well.” But then the triggers started to pull a little too tight. In 2003, Cynthia’s father, with whom she had been reconciling, passed away suddenly. He was diabetic and when he had to have his leg amputated, the surgery resulted in a fatal blood clot. Around the same time, Cynthia had been dealing with a new boss who was “bullyish” and a new co-worker who reminded her of her childhood perpetrator. It was a toxic cocktail of circumstances that caused her a great deal of stress and had her yearning to start using drugs again.

She reached out to Amethyst Women’s Addiction Centre and it was there that the light was finally reflected back on the root cause of everything. “I saw a counsellor there, and one of the first questions she asked me was, ‘Were you sexually abused as a child?’” says Cynthia. “I just kind of looked at her and I remember saying, ‘Well, what do you mean by sexually abused?’ And then I just broke down. It just all came spilling forth.”

In sharing her story, in finally unburdening herself of the horrible secret she’d been harbouring, Cynthia was able to put the pieces of her shattered self together. “Up until that point I didn’t understand why everything felt so fragmented and why I had all these crazy things happening. ‘Fragmented’ is the best way to put it because it was like bits of me were everywhere. But suddenly the drugs and alcohol and promiscuity and feelings of such low self-worth and depression and panic, it all started to come together and make sense. It was (through my counselling at Amethyst) that I really started to heal.”

Delving into such dark matter isn’t easy. As Cynthia says, “it got a whole lot worse before it got better.” But with her family’s support, she kept working through it.

She started going to a weekly group therapy session for female survivors of child sexual abuse. It was through those meetings that she had what was perhaps her biggest breakthrough. “I started to see that I wasn’t the only person (to go through what I did).”

It’s at this point, and only this point, in telling her story that Cynthia starts to cry. Not when confiding the details of her abuse, of the graphic emotional and physical violence done to her, but in acknowledging the resulting feelings of self-loathing and worthlessness, and the realization that she isn’t bad or crazy—that her responses, all of them, were perfectly normal responses to obscenely abnormal acts.

“All the craziness started to make sense,” she continues in a choked voice, “and the women helped validate that I was a good person, that I really am not a horrible monster and that it wasn’t my fault.”

From left: Lauren and Julia, Ottawa, Ont., 2011, Photo: Shirley Bittner

Out of the woods (comes something good)

In the same year Cynthia began disclosing the truth about her childhood, she was laid off from her high tech marketing job. At the time, she says, “it felt like my world was crashing apart. But when I look at it now, it was probably one of the best things that could have happened to me, because I needed to heal. I needed the space.”

Having been through the program at Amethyst, and with the cushion of a severance package, she decided to challenge herself. She rented a cottage near Algonquin Provincial Park, packed up her camera and some writing supplies, and headed off for five days on her own. It was during that trip that she finally ventured back into the woods—into what had been “a really scary place” in her life.

At first, she took a short walk down one of the well-travelled paths. But then she went back the next day and went a little further. By the third day, she says, “I walked quite far into the woods, off the beaten paths. And then I just sat on top of this hill and did some writing and I said to myself, ‘Wow, here I am. I made it.’ That was a really big moment.”

2003 was a year of many big moments for Cynthia, not the least of which was when she disclosed her truth to her mother. It was a warm day in May and they were sitting outside on her mother’s deck. “I said, ‘Mom, you remember that guy who used to look after us all the time?” says Cynthia. “And she said, ‘Oh, yes,’ and then I told her and she just kind of shut down. I think she was in shock. I don’t know that she’s ever really reconciled it.”

To this day, neither Cynthia nor her mother remembers the man’s name. Cynthia has “no clue” where he is or if he’s even alive. When I ask whether she’d want to try tracking him down through his former address or any other means, she has this to say:

“You know what, there have been days and times when I have wanted to go and literally stand in front of him and scream at him and show him, tell him what the fuck he did to me. I’ve had moments when I’ve been suicidal and I’ve come through and it scared me so much, and I’ve just been so angry that I’ve wanted to seek revenge. But I’ve come to a place where I would rather put my energy towards moving past what happened and really focus on the good I can do now, than go back into that. I think that would take me down a long path that would distract me from being able to help other people heal and to prevent this from happening to other children in the first place.”

Voice Found

Cynthia’s journey toward prevention started out with lobbying and blogging about her experiences (her blog is aptly titled Not So Bland). Then, in 2011, she launched Voice Found. She did it in part to honour her stepmother, Gwyneth Wood, who committed suicide in 1988 and whose inner turmoil stemmed from child sexual abuse at the hands of her brother.

She also did it “because I really, really wanted to do something about (the issue of child sexual abuse). When I was going through my own disclosure, I found it hard to find really good resources. The Amethyst program was great, but I would have benefited from a whole lot more therapy, and it’s really expensive. I realized there wasn’t a whole lot out there to help people and I wanted to help offer that.”

The more Cynthia thought about it, the more she wanted to focus on prevention as well as healing—something she wasn’t seeing nearly enough of in the community at large. “It still astounds me how many people don’t take the issue of child sexual abuse seriously. I think it’s just a lack of education and a lack of knowledge. And the fact that people just don’t want to imagine that it really is that bad and it really is happening in every neighbourhood, everywhere. It’s not just an ‘Over there’ problem; it crosses absolutely every social and economic background. Nobody is immune to it.”

Voice Found, through its website and its Stewards of Children® prevention training, offers plenty of advice on how to prevent, detect and respond to child sexual abuse. But perhaps the most important thing to remember is this: “Always, always, always believe a child.”

As per the Voice Found website, “disclosure of sexual abuse means a child has chosen you as the person he or she trusts enough to tell. It is the moment when children learn whether others can be trusted to stand up for them.”

As it stands, Voice Found is a 100% volunteer-run organization. Cynthia works full-time as a sales, marketing and education consultant, serving as Voice Found’s president on the side and often contributing her own income to help keep it going. Ultimately, she’d like to secure enough funding to hire an Executive Director and extend the organization’s reach, within the community and across the country. “It’s remarkable what we’ve accomplished, absolutely remarkable,” says Cynthia. “We deliver a lot of training, mostly in Ottawa but also across Ontario, in Saint John, New Brunswick, and in Iqaluit, Nunavut through Embrace Life Council. But there’s so much more that we want to do.

“I’m getting really angry at continuing to see news stories about how (Minister of Justice) Peter MacKay has announced a public sex offender registry and everybody thinks it’s great; that isn’t going to do much of anything. Longer sentences and public sex offender registries are good for those who are caught, but those sex offenders are just the tip of the iceberg, and I don’t want people to be complacent. Child sexual abuse is at the root of why so many kids are lost out there, are homeless, are pregnant, are drug addicts, are alcoholics, are struggling, are bullies or being bullied. If you dig to the root cause, so often you’re going to find the root cause is childhood trauma, and mostly from sexual abuse in some way. I’m trying to find a way to get that message out. People need access to evidence-based programs that will educate adults about what they can do to prevent the abuse from happening in the first place. ”

Of course, the bigger question remains as to why child sexual abuse is so prevalent—why so many children grow up to become perpetrators, why some adults and even teenagers feel the need to exert power in such a horrendous way, why there are people who are so sick in heart and mind that it would ever happen at all. But as long as it is happening, children need a voice and adults need to learn how to hear it. And given how frequently sex offenders are revealed to have been sexually abused as children, preventing our youth from being assaulted not only protects the innocent today, but also could potentially lower the number of perpetrators tomorrow. Prevention, however it happens, is worth investing in.

Becoming whole

While Cynthia gets the message out and gives voice to those who would otherwise remain silent, she continues to heal herself. Her hard work has led to a better understanding of herself and of the “whys” of her panic attacks, depressive disorder and destructive life choices. “Life is better when you can make sense of things,” she says.

She feels confident in her own skin and on her own two feet. She and Ian ended their marriage in 2009 because, she says, “I needed to be on my own and really get good with myself.” But they remain “the best of friends.”

And she’s endlessly proud of her four children: Adam, 28, a musician and web designer who was married last year and is expecting his first child this year; Brandon, 26, who co-founded Tattoo hero and recently spoke out in a United Way video about his experiences with depression; 19-year-old Julia, who has also been courageous and honest about her mental health struggles; and 19-year-old Lauren, who is “realizing her dream” of studying at St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

From left: daughter-in-law Amanda, Adam, Cynthia, Brandon, Julia and Lauren, Ottawa, Ont., 2013, Photo: Suzanne Sagmeister

“They’re absolute sweethearts, all four of my kids,” says Cynthia. “They’re amazingly well adjusted, just really good, genuine, authentic kids. I’m very, very blessed.”

Cynthia has other challenges in her life, beyond the ongoing burden of coping with the lingering effects of sexual abuse and the occasional cravings to start using again. Her beloved brother Mark died of lung cancer in March 2013, and her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer in October of the same year. (“But she’s not going to die,” says Cynthia, who accompanied her mother to her last chemotherapy session the day of our interview. “She’s going to be okay.”) Still, she feels more in control, more whole, than ever before.

With that sense of wholeness, she’s able to truly see herself, literally as well as figuratively. She describes in a blog post how she finally met her gaze in the mirror in 2009. Speaking to me, she recalls that “I was kinda scared to do it, but I started just having a glance; for the longest time all I would do is just glance. And then eventually I really looked and I started to see what other people had told me. People had always said I had really gorgeous eyes, really beautiful eyes and I didn’t see that for myself. And when I looked inside, I saw everything. I felt sadness but I also saw a lot of strength. A lot of strength. I saw that and I said, ‘Hey, I’m really okay. You know, I’m really okay.’ And I do have beautiful eyes.”

Photo: Shirley Bittner

In her initial email to me, Cynthia wrote the following: “I don’t consider myself an inspiration, although I’ve been told that I am. I really just want to make positive change… Out of my pain, I have chosen to use my voice for good. So, I started Voice Found to educate adults on prevention, and support adult survivors and give them hope.”

Now, I recall the words I quoted from her email earlier, that she’s “no famous ‘star’ or celebrity.” Maybe not a celebrity. But there’s no question Cynthia is a bright star lighting up the darkness. And she is absolutely a Kickass Canadian.

* * *

To reach Cynthia, email [email protected] or follow @cynthiabland on Twitter. For more information, visit Voice Found, and follow @voicefound on Facebook and Twitter.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Cynthia Bland is no celebrity but she should be. Thank you for sharing this very moving and insightful story. So often during these awful crimes the focus is on the offender; catching him, locking him up and making sure he’s on the list. So little focus is put into the ripple effect on the victim and victims’ families. And I like how it was also mentioned that these are only the crimes that are reported. I know from past experience that there are indeed many assaults that go unreported. Kudos to you Cynthia for overcoming your fears, using your internal strength and creating such a positive organization!

Thank you, Penny! I agree – Cynthia’s story deserves to be told. She’s a remarkable woman.

Penny – Thank you for your kind words. I continue to be astounded at how taboo this topic remains. People need to face it and take action to prevent it.

Congratulations to you both, Cynthia and Amanda, for giving voice and a forum to this fundamental issue.

Cynthia, your courage and honesty are an invaluable inspiration to all, and testament to goodness and to the triumph of the human spirit. Your work with Voice Found and Stewards of Children is critically important in increasing public awareness of child sexual abuse and promoting prevention and healing. Congratulations and thank you.

Thanks to you, Catherine. I wholeheartedly agree. Great to see Cynthia getting the support and recognition she deserves for her strength and courage.

Thank you for your kind words, Catherine. We really do need more people talking about the issue of child sex abuse and taking action to prevent it.

This is a great site and what a great decision to accept Cynthia’s submission. I think the subject of child sexual abuse is overlooked and invisible in our society. It happened to me as well and, along with other factors, it kept me very divided for far too long. I decided to join forces with other like-minded individuals on Twitter so we can gain collective strength. Thank you Cynthia! I look forward to taking your training in the near future. Bless you!

Thank you for sharing, Shirley. I’m sorry you went through that. I hope you’re finding peace and comfort. So glad Cynthia’s story is helping people.

Brilliantly and poignantly written article about a woman whose passion and strength to stand up and be heard will create change. Kudos to you both!

What a touching comment, Suzanne. Thank you. And I fully agree – Cynthia is already making a difference, changing and saving lives.

I met Cynthia in 2014 when I took my first workshop she offered with Voice Found after we connected through Facebook. I knew this woman was special when I met her. I heard some of her story and the difference in the world that she wants to make. As a single mom I understand the threat of child abuse and how it can affect your children. This is something I wish had been available to me so many years ago, but I am ecstatic that it is available now. Cynthia, thank you for sharing so much more of your story. Amanda, thank you for making this exception. Cynthia is a Kickass Canadian and I am glad she nominated herself! The courage to share her story, and make Voice Found happen, is amazing. I believe in preventative medicine, and teaching responsible adults is a HUGE mission and a very important one. We need to make this a priority. Get these workshops to everyone who is involved with children, whether that is a parent, teacher or recreational coach. The more we can be educated, the greater the chance is that this won’t happen to other children. Koodles to you my friend! I’m so proud to know you. Hugzzz

Thank you, Liz. What a beautiful comment!

Bravo.