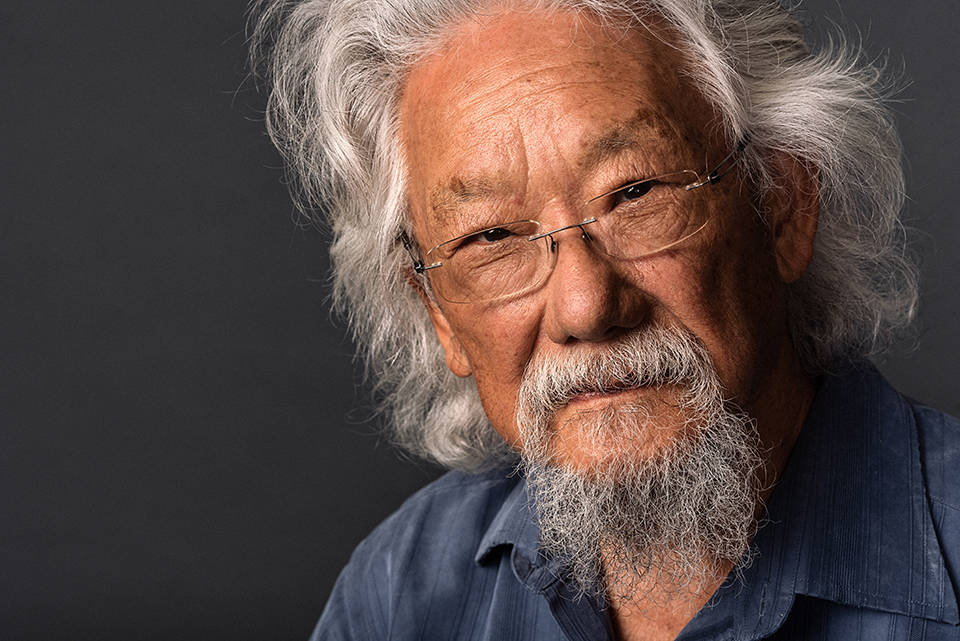

Dr. David Suzuki, environmentalist-scientist-educator-grandfather

“I don’t think you can talk about environmental issues without talking about issues of how we treat each other.”

Photo: Jennifer Roessler courtesy of David Suzuki Foundation

What’s the most important thing about David Suzuki?

“He’s a grandfather. And he teaches his grandchildren about insects.”

That answer comes from my young daughter. It’s largely based on her love of David’s latest children’s book, Bompa’s Insect Expedition. But it’s still spot-on.

Dr. David Suzuki has a long list of credentials. Celebrated geneticist, world-renowned environmentalist, award-winning broadcaster (including the Canadian Screen Awards’ 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award), Doctor of Zoology, Companion of the Order of Canada, Member of the Order of British Columbia. He spent 44 years hosting television’s longest-running science show, CBC’s The Nature of Things, and authored more than 50 books. He was inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame and received UNESCO’s Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science, the 2009 Right Livelihood Award and UNEP’s Global 500 Award. In 1990, with his wife, Dr. Tara Cullis, he co-founded the David Suzuki Foundation, an evidence-based non-profit that continues to lead the way in its mission to “conserve and protect the natural environment, and help create a sustainable Canada.”

Yet if you ask him, his life and career distill down to the fundamentals: respecting all living things, including insects—the most numerous, diverse group of animals on our planet and the source of inspiration for David’s work as a geneticist; and nurturing what matters most to him—family, especially his five children and 10 grandchildren.

In David’s words: “The most important assessment is that, at the end of my life, I hope I will be able to see every one of my grandchildren and say, ‘Look, I’m only one human being but everything I did, I did for you, and I did the best I could.’”

“Everyone knows and loves David Suzuki as the godfather of environmentalism in this country. He inspired all of us to love this Earth and to grow up wanting to defend it. But what I love the most about David Suzuki is that he does not mince words—that man will kick all of our asses to try wake us up to the damage that we’re doing to the planet.” —Kickass Canadian Adria Vasil, Corporate Knights managing editor, author (Ecoholic series)

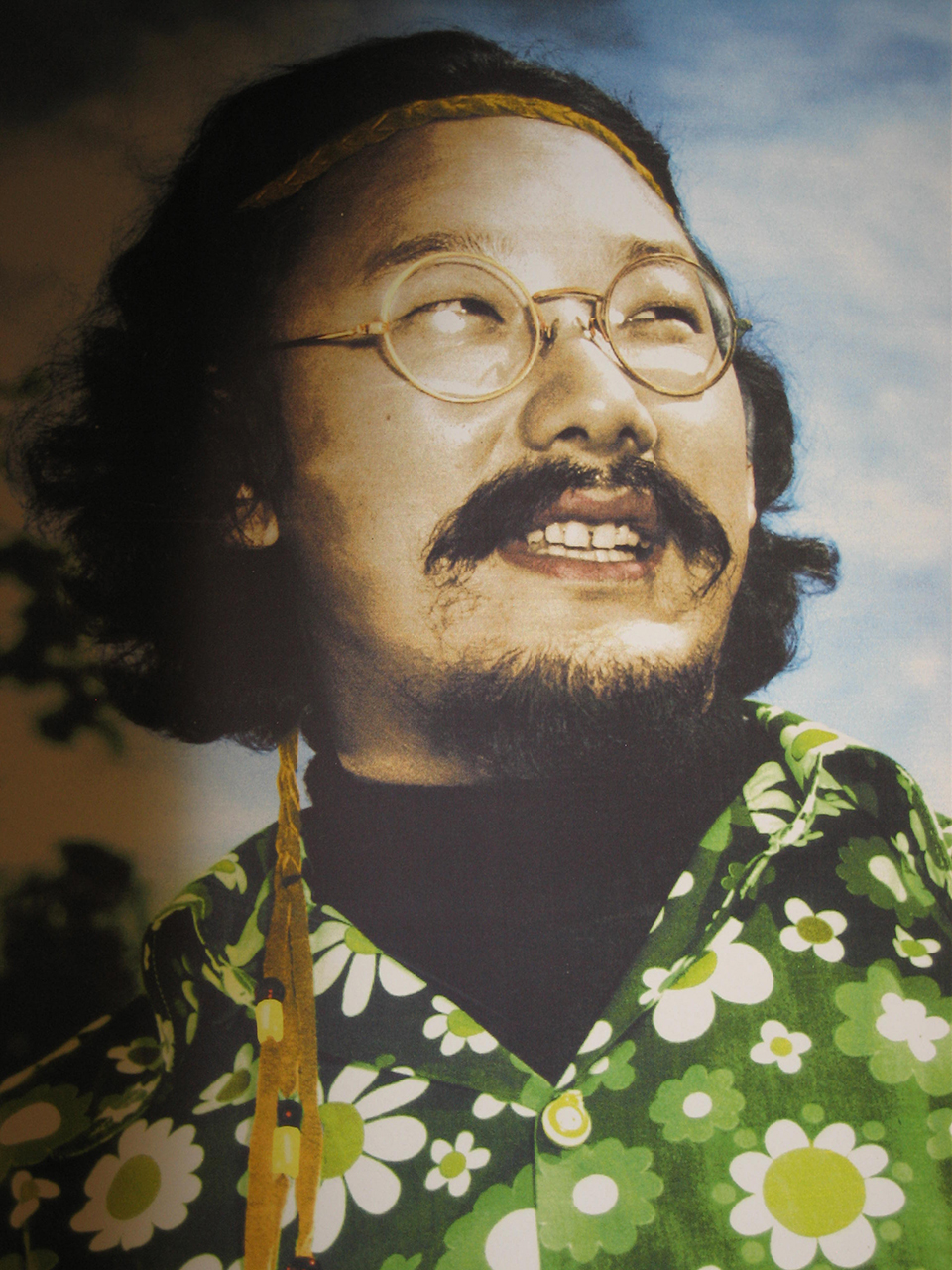

David in his younger years

Origins

The beginning of David’s life has been well documented, including in David Suzuki: The Autobiography and the NFB documentary Force of Nature: The David Suzuki Movie by Icelandic-Canadian director Sturla Gunnarsson. So, I’ll mention only a few points.

In Force of Nature, David cites Pearl Harbor and its repercussions as among the most formative events in his life. In 1942, the War Measures Act drove his family from their home in Vancouver, B.C.—where David and his siblings, as well as their parents, Carr Kaoru Suzuki and Setsu Nakamura, were born—to an internment camp in Slocan, B.C. It was there that David first encountered discrimination—from the other Japanese-Canadian children, who shunned him because he couldn’t speak their language. So, he found solace where he could: he went fishing.

When the family moved to Leamington, Ontario in 1946, David was again discriminated against, this time by white people. The Suzukis were the first visible-minority family to live in Leamington, which was, at the time, a place so racist it prided itself on never having had any people of colour stay long enough to see sunset. So, David turned to nature once more; he went to the swamp—a source of endless wonder and inspiration for him.

Things somewhat improved when the family moved to London, Ontario, where David graduated from London Central Secondary School in 1954. There, he met Setsuko Joane Sunahara, who later became his first wife and with whom he shares children Tamiko, Laura and Troy. He was also elected student council president in his last year of high school, a role that brought about one of many lasting lessons from his father. When David took a weak stance on a school issue because he wanted to be liked, Carr told him: “If your goal is to be liked by everyone, you’ll never stand for anything. But if you believe in something, you have to stand up for it and expect people to fight against you.”

After high school, David took his studies to the U.S., graduating from Massachusetts’ Amherst College in 1958 with a BA in biology, and from the University of Chicago in 1961 with a PhD in zoology. His work as a scientist began with insects: he studied fruit flies, famously co-writing a book with Anthony Griffiths that became the most widely used genetics text in the U.S.

David taught at the University of Alberta for the 1962–63 school term, which proved to be one of his most formative years. While there, he read the book that led him to environmentalism: Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. On the David Suzuki Foundation website, he writes that the book “put science in its place for me” by highlighting its tendency to study parts in isolation without considering their connection to everything else; for example, “the devastating repercussions of DDT, including the discovery of biomagnification—concentration of molecules as they pass up the food chain.” That same year, he gave a lecture on Edmonton’s CBC channel, Your University Speaks, which tuned him in to television’s potential to reach a wider audience.

In 1963, David returned to Vancouver, where he taught at the University of British Columbia for the rest of his academic career and has lived ever since. His broadcasting career took off with the CBC television series Suzuki on Science from 1971–72. (1972 is also the year he married writer and environmentalist Tara Cullis; they went on to have daughters Severn and Sarika Cullis-Suzuki.) He hosted CBC’s show Science Magazine in 1974 before founding and hosting CBC Radio’s Quirks and Quarks. In October 1979, David took over as host of The Nature of Things, where he stayed until his final episode in April 2023 (the show is now co-hosted by Sarika and Anthony Morgan).

“David Suzuki has been a global climate leader for decades. Very grateful that his CBC Radio series It’s a Matter of Survival put global warming on my radar in 1989. He and his Foundation staff appeared in the video of my climate song ‘Cool It’ in 2007.” —Raffi Cavoukian, C.M., O.B.C., Raffi Foundation for Child Honouring founder, David Suzuki Foundation honorary board member

With wife Tara Cullis, David Suzuki Foundation co-founder & president

The web of life

One episode of The Nature of Things in particular shaped David’s understanding of our natural world: the 1982 documentary ‘Windy Bay,’ which took him to Haida Gwaii, B.C., where he explored the fight against local logging operations. When David asked Haida activist and artist Guujaaw why he opposed the logging, he replied that without the trees, he and his people would be just like everybody else. To David, that underscored the Haida’s deep connection to the trees, the land, the water, the air.

“You talk to any Indigenous person, they think that there are spirits in the rocks and the rivers and the mountains,” says David. “They talk about their brothers and sisters, the winged ones and the four-legged. Genetically, it’s absolutely true. If you look at the genes in plants or animals, the vast bulk of those genes, we share. We are related through our evolutionary history.”

It’s an ecocentric viewpoint that David has tried to impart to others—without success, in his opinion. “I see myself, and the environmental movement as a whole, as a failure because we didn’t change the way people saw their relationship with the rest of the world… We are just one strand in a web of relationships. When you’re in a web, anything you do has repercussions—the whole web vibrates—so you have responsibilities. That’s what people have understood since the beginning. But in the last few hundred years, we’ve abandoned that idea. We’re so impressed with ourselves that we now think we live in a pyramid—not a web, a pyramid where we’re at the top and everything down below is for us.”

David calls out the industrial revolution for opening the box on a time when humans hold themselves above the rest of life, unbound by nature, limited only by our imaginations. But he looks back further to identify the true roots of anthropocentrism: religion, “especially the Judaeo-Christian religion that suddenly elevated humans out of the web of nature,” and the Renaissance, which saw French philosopher and scientist René Descartes declaring cogito, ergo sum—I think, therefore I am. “Intelligence was the key to our survival,” says David, “but when you elevate that intellect as if it’s everything –”

He extends the blame to English philosopher Francis Bacon’s scientia potestas est—knowledge is power—and English physicist Isaac Newton’s reductionism. “Newton’s idea was that you look at a little piece here and a little piece there, and eventually you’ll fit them all together and you’ll have an explanation for the whole. What we’ve found is, that doesn’t work. Because you can look at this part here and this part there, but when you put them together, they interact. There are what we call emergent properties that come out of the combination, that you can’t anticipate by looking at the parts. But we continue to run on the Newtonian idea, looking at nature in bits in pieces.”

David points to a key scientific contribution his lab made in 1971, in which they discovered a temperature-sensitive mutation in fruit flies that affected whether or not the insects could move. “I got a big grant when we discovered this mutation. Why? Because nerves in fruit flies are the same as nerves in people. So, by studying this nerve mutation in fruit flies, we could discover things that were important to people.”

Next, he outlines the dangers of neonicotinoids (neonics), pesticides that act as a neurotoxin, which “we as environmentalists have been fighting.” Not only do neonics contribute to the decline in bee populations, they also pose other, more direct threats to humans. “They kill insects by killing nerves,” says David. “Think about that. Suzuki got a grant to study nerves in insects because the nerves in insects are the same as nerves in humans. We’re putting a poison into the seeds of what we are going to eat, to kill insects, as if, somehow, we don’t think that’s going to affect us?!

“To me, the most destructive thing is that we don’t think we’re part of nature… We don’t see the connection.”

“It was May of 2000, deep in a remote coastal fiord in Gitga’at Territory, that I first met David Suzuki and his wife, Tara. I had just been hired as a wilderness guide by King Pacific Lodge and we were invited guests of the Gitga’at people for the opening of a new Raven Longhouse in Cornwall Inlet. Cornwall Inlet, spectacular with its steep granite walls and lush temperate rainforest, was slated to be logged later that year. David Suzuki and Tara were there along with Robert Kennedy Jr. and all of the hereditary chiefs of the Gitga’at Nation to put a stop to the logging. I remember David was not feeling well, and as we sat around the fire in the longhouse, Tara spoke about the importance of the land and protecting wild spaces and the temperate rainforest. It was a watershed moment for me on the coast that would later propel me to stand up for the Great Bear Rainforest, inspired by the Gitga’at people and the incredible work of the David Suzuki Foundation.” —Kickass Canadian Norm Hann, Norm Hann Expeditions founder, filmmaker (Anthony Bonello’s Stand Film)

“I count David among my friends and have worked with him in many situations to raise awareness of our need to protect the environment. David is a warrior and a leader in our fight to protect the environment. I will support him whenever I can.” —Kickass Canadian Roy Henry Vickers, Eagle Aerie Gallery artist

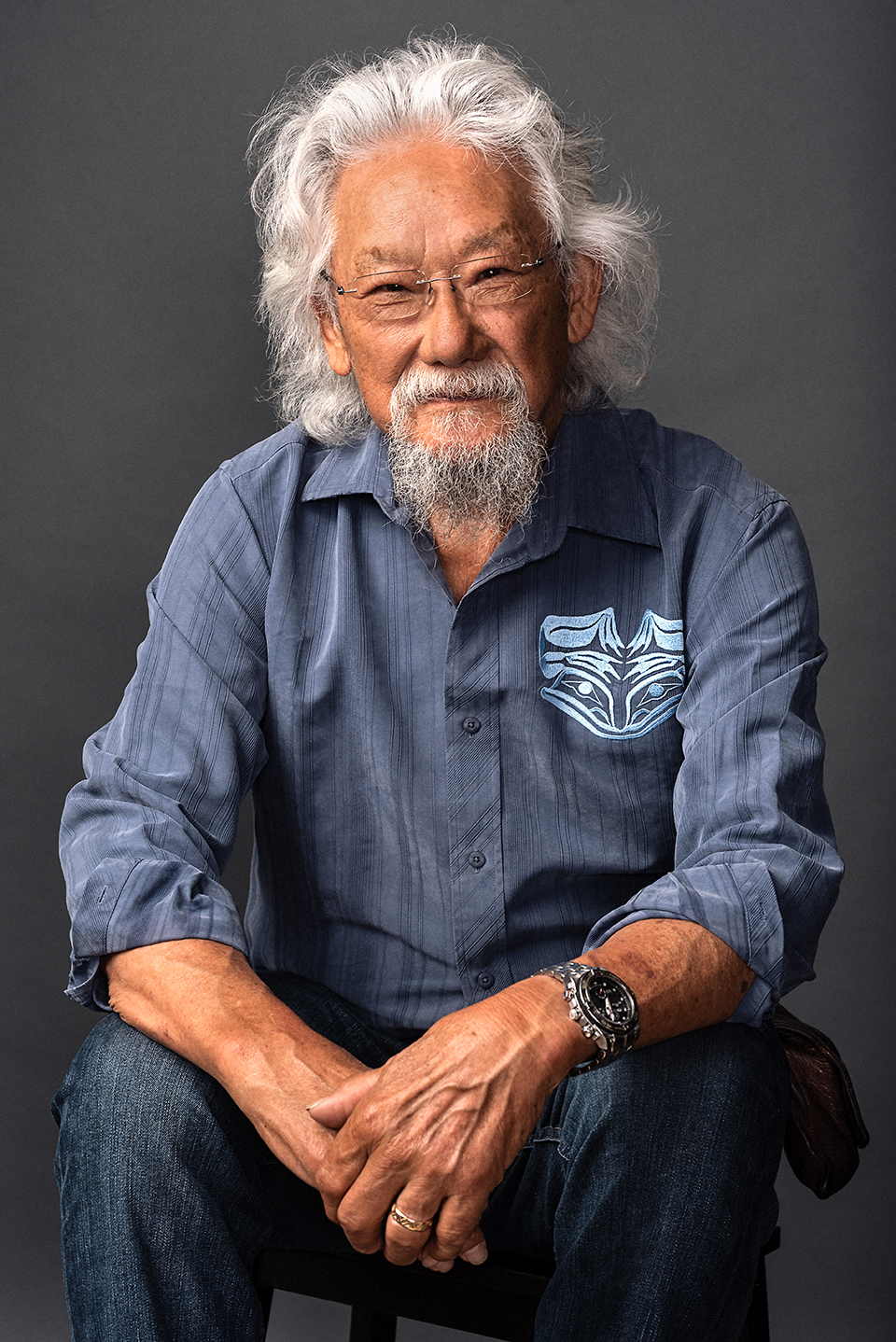

Photo: Jennifer Roessler courtesy of David Suzuki Foundation

The politics of change

These days, it can be difficult to have even a reasonable conversation about key issues, let alone agree on solutions. We’re seeing a global decline in democratic governance and a drift toward authoritarianism. ‘Divisiveness’ has become almost a catchword of the times.

“The way it is now, it’s like, ‘I’m right and you’re an asshole,’” says David. “There’s no opportunity, then, to share ideas and see where we’re right and wrong. It’s a terrifying situation. I thought catastrophe would result in a greater enlightenment and we would behave differently. Every day now the planet is setting new temperature records and you’re seeing disasters unfold. If this isn’t enough –

“As long as this issue remains political, we’re not going to do anything.”

David flags the pandemic response as a model for how government and industry should address the climate crisis. “We had an emergency, and who would have believed before the COVID crisis happened that people would have locked themselves away for six months? I mean, what an astounding thing we did. Who would believe the money?! Suddenly we’re not talking millions or tens of millions; the government spent $300 billion on the COVID emergency. Where the hell did that money come from?! We just cranked it out. And that’s what we need now.”

But voting—although important—is not enough, he says. Our political revolving door, with its shake-up every few years, means we can’t rely on any one party or leader to fix things. He recounts running into one of his longtime supporters from B.C., who is now a Member of Parliament for the Liberal party. “I said, ‘Listen, you guys are in power now, you’ve gotta declare an emergency and start spending money and you’ve gotta say that we’ve gotta get off fossil fuels very, very quickly, that there are huge opportunities in renewables, we have to go that way.’” The MP replied that he couldn’t take action for fear the opposition would win the next election.

“We say we belong to a democracy,” says David. “Anybody who’s concerned about climate change, species extinction, you’ve gotta tell these people we’re electing to office—doesn’t matter what party—you’ve gotta tell these people: ‘This is my highest concern. What are you doing about it?’ Now, if five or six people do that, they… ignore it. But if hundreds of people start banging away, guess what? They will respond.”

He cites “a classic example” of how this can work: “(Ontario Premier) Doug Ford doesn’t give a shit about the environment, and he showed that when he opened up the greenbelt around Toronto and started handing out development permits. There was such a massive response from all kinds of organizations and people that a year later he had to crawl back on his belly and not only apologize to Ontarians, but take back all of the stuff he passed—and he reneged on them. That is an example of what you can do to a politician. But that’s gotta be done to all of the politicians. Anyone running for office has got to realize that (the environment) is what people think should be our highest priority—now let’s get together and work together on the solution.”

“For over 40 years, the name David Suzuki has been synonymous with ‘the environmental movement.’ Canada has never known a science educator with the social and political impact of David Suzuki. Kick ass, he does!!” —Kickass Canadian Elizabeth May, Green Party of Canada leader

But what can I do?

David is clear that systemic, institutional change is essential. He’s equally clear that each of us can make a difference as an individual. When people tell him they feel too small and insignificant to effect change in the face of such a mammoth crisis, he says this: “Enough drops will fill any bucket.”

He points out a simple action we can take immediately to make a big impact: consume less. On the David Suzuki Foundation website, he writes that population growth is already slowing, stating that 10.4 billion humans are expected by 2080, “followed by a levelling off.” A far more pressing concern than overpopulation—and a quicker issue to address—is excessive consumption in the Global North.

“I challenge anyone who cares about the environment and wants to do something, to cut your consumption by 50% in a year,” says David. “I am sure we can do it. Let’s start thinking about how every bit of what we consume comes out of the planet, and when we’re done with it, it goes back into the Earth. Let’s make ‘disposable’ the most obscene word in the English language… Nothing is disposable, everything goes back into the Earth.”

He talks about how the Great Depression shaped his parents’ outlook and values—save some for tomorrow, share with others—which they “drummed into” him and his three siblings. “The most important lesson was: you have to work hard for the money to buy the necessities in life, but don’t run after money as if having fancy clothes or the latest car or a big house somehow makes you a better, more important person. That’s not what life is about.”

“David Suzuki has not only educated a global population for decades on environmental issues and climate change, but has exemplified what it means to live a good and meaningful life. His care, his character and his commitment to being a steward of this planet is something we should all strive for.” —Kickass Canadian Colin Harris, Take Me Outside founder, author (Take Me Outside – Running Across the Canadian Landscape that Shapes Us)

David’s daughter Sarika Cullis-Suzuki, The Nature of Things co-host; photo courtesy of David Suzuki Foundation

Where value lies

We seem to have strayed far from what matters most. When people share stories of what loved ones say at the end of life, there’s no mention of money or material things; their memories of family and friends, shared connections and experiences, are what float to the top as they drift off.

Yet too many of us spend our lives driven by values that don’t fulfill us. Our disconnection from nature has metastasized into a fundamental disconnect from ourselves—or perhaps the other way around. Instead of honouring our natural state and what truly brings us meaning, we overlook our intrinsic worth, obsess over image, status, celebrity, youth.

And then there’s what we do to one another.

Despite evidence of how humans have overvalued our place in the world, there are far too many examples of how terrible we can be to our own species. David describes an email he received from a woman in Ukraine who wanted his help advocating for an animal that was endangered due to the war. “I wrote back and said, ‘Look, war itself is one of the most ecologically destructive activities. But if we’re willing to treat each other this way, how can you expect people to care about the animal that you’re worried about, or plants or anything else?’

“I don’t think you can talk about environmental issues without talking about issues of how we treat each other… If we had an economy in which money wasn’t the thing we’re all running after, we would treat each other very differently.”

He calls it “an obscenity” that any one individual should be worth a billion dollars. “Why should a small group of people be able to corral that much money? Think if that were distributed throughout the population, how different life would be.”

“David Suzuki is an exceptional human and Canadian icon who has devoted his life to trying to restore balance to our world. When we abuse our natural surroundings, it’s an assault on humanity as a whole. And, like war, it’s a symptom of our dysfunction. David is leading the way to a more peaceful, equitable, sustainable life for us all. For that, he has my deepest gratitude and respect. It is truly an honour to simply be in his presence.” —Kickass Canadian Dr. Samantha Nutt, War Child Canada & War Child USA founder & president, David Suzuki Foundation honorary board member

David’s daughter Severn Cullis-Suzuki, David Suzuki Foundation executive director, with husband Judson Brown & their sons

Remember the future

The reality is that we are animals. No matter what innovations our imaginations conjure, our basic needs are determined by biology. We can’t elevate ourselves above that—not even with a ticket to Mars or an uploaded consciousness (talk about having your head in the clouds).

If we’re so intelligent, so creative, let’s use that for good. Science isn’t inherently bad; it’s brought us brilliant advances and discoveries that have saved and greatly improved lives. There’s a scene in the documentary Force of Nature where David revisits the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, where he was a biology research associate from 1961–62. He explains that, in the 1940s, the lab was used to refine uranium for the Manhattan Project. Yet from that destructive history, it became a leading research institution, one that shaped David as a scientist.

We have the potential to learn from our mistakes, to mine our expertise and find the right way forward. Our extraordinary planet provides so much. If we discovered today that Mars has everything Earth offers—right now, in its current state—we’d see it as a paradise. All the solutions are available to us. We just need a holistic, harmonized approach that balances economic benefits with the health of people and nature. We all stand to benefit—and we owe it to those who come after.

In David’s words, “reduce your consumption and get down to basic things. Spend more time with your children and grandchildren, and stop buying all this frivolous crap.”

After dedicating decades to the environmental, peace and human rights movements, David has “no idea” whether people will be able to course correct—to rediscover their place in the web of life, to better care for the planet and each other. “All we can do is do the best we can, and then hope that some lessons come out of that and will be carried on… I did the best I could and I am shocked and delighted that one of my daughters [Severn] has taken over the Foundation, and another daughter has become a co-host of The Nature of Things. So, to the extent that I have a legacy, they will carry it on.”

He doesn’t give his grandchildren specific guidance about the planet and our future. Instead, he says, “I just take them out in nature as much as I can.” He and Tara spent the COVID lockdown at the family cabin in B.C., with Sarika, her husband and their three young children. It’s a time David calls “the happiest six months of my life… Every morning, rain or shine, (my grandchildren and I) went outside, into nature… It was absolutely pure joy. I don’t have to tell them anything; they know—they love nature.

“It’s interesting, when I was a kid, I was an avid insect collector, I loved beetles. Today, of course, my children and grandchildren all are interested in insects. So, I said, ‘Let’s start making an insect collection.’ (My grandchildren) said, ‘No, no!’ They don’t want to kill insects. They said, ‘Let’s start a photograph album; with your cell phone you can take a picture.’ There’s a very different mentality now because we’ve declared war on insects and they know that killing these things just at random is not good. It’s a big shift.”

David is a big part of that shift. It might seem to him that he and the movement have failed. But I think of how different my daughter’s school experience is from mine. Her teachers ask the children to reuse recyclables as craft supplies, encourage them to bring litterless lunches. They, too, teach them from kindergarten about the importance of insects and all animals, and why not to pick living plants when they go for group walks. Indigenous educators regularly visit the school, imparting their wisdom and sharing traditions, especially with regards to reverence for nature.

We haven’t shifted course with the urgency David wants. But in his unwavering advocacy for the environment, he has inspired countless people across generations and countries, planting the seeds for us to find our way back. Change is in motion, and there is no failure in that.

* * *

For more on David Suzuki and his Foundation, please follow along on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube.

Thank you to Deanna Bayne for making this interview possible.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

What an inspiring article, Amanda, and what a life well lived. I love the no-nonsense straight-talk that Suzuki has always been known for. Many thanks to both of you for sharing this story.

Thank you, Sonia! I hope the article offered some of the answers you were looking for. It was a privilege to speak to David, and I’m honoured to feature him here.

Wow, Amanda, what a great article and testament to David. He has been such an amazing inspiration to so many Canadians, and has such a massive impact on Mother Earth through education, awareness and protection.

Thanks, Norm! Grateful for the work both David and you do to protect our natural world.

This is wonderful, Amanda. It is lovely to see how your intelligence complemented David Suzuki’s.

That’s quite the compliment, Frank! Thank you for saying so. Really glad you enjoyed the piece!

Great to read a new Kickass Canadians article, and such a well-researched one on a truly iconic Canadian. Well done, Amanda!

Thanks so much, Tom! Happy you liked it.

Excellent article, Amanda! David Suzuki is an inspiration to us all. I think he would be happy to know that we spend hours at the cottage examining and researching insects with our grandchildren.

That’s wonderful, Helen! Thank you for reading 🙂

Thanks, Amanda, for the great article! I once had the opportunity to hear Dr. Suzuki speak (many years ago!) and it was an event that marked me forever. 🙂

Thank you, Cheryl! Awesome that you got to hear him speak.

Thank you, Amanda, for this comprehensive and sensitive article on the lifelong and continuing contributions of Canadian icon Dr. David Suzuki. And for the privilege of being able to reflect on his meaningful and transformative impact on our understanding and appreciation of the interconnectedness of our precious living world.

Many thanks, Catherine!

What a fabulous article with beautiful photographs of David Suzuki and his family! Dr. Suzuki has been correct all along with his findings, his lifestyle, his experiential approach to education, his values around the natural world, and his thorough understanding of the interconnectedness of all life. He lives in harmony with this planet. We all need to watch and listen to him. We need to act like him. How wonderful that his daughters are furthering his legacy. That’s a successful life!

Marney, thanks so much for your thoughtful comment. Glad you found and enjoyed the article!