Henry Smith, video game developer-wizard

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: April 3, 2014

“You can create an entirely new world... It’s pretty amazing; it’s the closest thing to making magic.”

Henry Smith is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. He tries to deny it, but his seemingly endless supply of ideas, creations and inventions, not to mention his razor-sharp wit, does little to support his argument.

I first crossed paths with Henry at Ottawa, Ontario’s Glebe Collegiate Institute, the high school to which we’d both recently transferred. He’d moved from a small English village near Cambridge in 1993, when his Canadian-born parents decided to return home after a 20-year stint across the pond. I don’t remember the exact moment we met, but I do know that Henry sat behind me in a Grade 11 math class, and that I’d try to compete with him to see who could finish assignments first. (I’ll call it a draw; my artistic licence is valid.)

Even then, as a teenager, he had an obvious thirst for challenge and a strong desire to blaze his own trail. Example: Our math teacher often included a bonus question on quizzes, which was always much more challenging than the rest of the test. So of course that was the question Henry tackled first. Then, if he had time after demolishing the equation, he’d get through the rest of the test. Marks weren’t terribly important to him (although that didn’t interfere with him winning provincial academic awards and stealing the show at science fairs). He was more concerned with exploring new things than conforming to standards.

We’ve stayed in touch since those high school days, and that friendship has been a privilege. Henry’s sense of individuality and independence, not to mention his uniquely clever mind, are endlessly inspiring to me. I often look to his example or wisdom when feeling insecure about my own approach to career and life. He’s unafraid of living according to his own principles, and it has served him very well.

Today, he’s at the beginning of a very exciting stage in his career as a game developer. In summer 2012, he left his job of seven years as a user interface programmer with BioWare to delve into his indie career. Under the company name Sleeping Beast Games (inspired by an episode of Cowboy Bebop), he launched his “practise” project, a local, multiplayer iOS game called Spaceteam, to great success and is about to start work on what he calls his “more ambitious” project, Shipshape.

But truth be told, his indie career began many years ago and even more miles away. It started with a bright, curious little boy living in England, whose father worked in artificial intelligence and always had a computer on hand, and whose mother’s creative flair was deeply infectious…

Sleight of hand

From what I can see, both of Henry’s parents played a big part in making him who he is today. Arnold Smith spent much of his career as an AI research scientist for the National Research Council Canada. Louise Mortimer taught ESL at Carleton University while in Canada, but she also has a strong musical background; she’s currently a cellist for the Ottawa Chamber Orchestra and Ottawa Symphony Orchestra, and a volunteer teacher for OrKidstra, run by Kickass Canadians Tina Fedeski and Margaret Tobolowska.

From left: Louise, Henry and his fiancée, Sara, Gatineau, Que., 2012

Both these influences—with their winning combination of logic and creativity—inspired young Henry, who never let his hands stay idle for long. He started making video games before he hit 13. But before that, he whet his appetite by drawing, making board games and card games, and, of course, building Lego constructs. He also played the piano and clarinet, though he remembers hating practising: “I loved to improvise and just do my own thing.”

He says his passion for making video games comes from a combination of all his interests. “I can make music and write stories and design art and solve puzzles. And I have to work with logic problems to make the game work. With programming, I can make things come alive. You can have an idea and program it and you can create an entirely new world or creature on the screen. It’s pretty amazing; it’s the closest thing to making magic.”

For Henry, the first glimpse of that magic came from playing on his friend’s Super Nintendo and old Amstrad computer. After gorging on games, like Street Fighter II, F-Zero and Dizzy, Henry set about making his own versions using HyperCard. “I didn’t copy them because I thought there was something I could improve about them,” he says. “I copied them because I loved them and I wanted to do the same thing… I wanted to be involved in creating a world like that.”

His younger brothers, Julian and Daniel, often pitched in, drawing on their own musical and artistic talents. (The whole Smith family is quite impressive; Julian is a published fiction writer living in Port Maitland, Nova Scotia, and Daniel is a professional cook and baker in Toronto, Ontario). Henry says that none of these “very simple, half-finished games” went anywhere. But they opened the floodgates for his learning and creativity, which ultimately led him to making his first finished game.

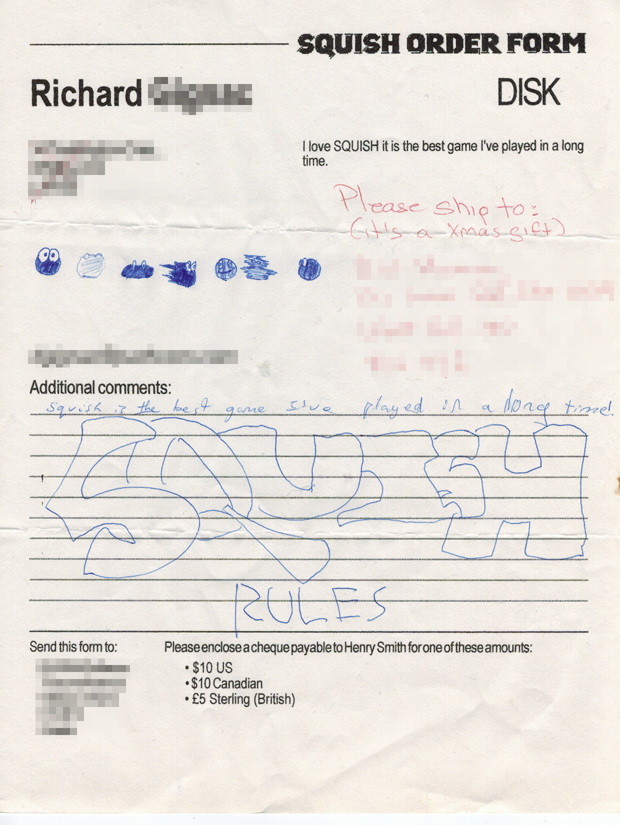

Squish

One of the first things I remember learning about Henry is that by the time he was in high school, he was already earning royalties from a Mac shareware game he’d made—Squish, inspired by the game Lemmings.

But it was another favourite childhood game that showed him the value of truly committing to his projects: TaskMaker. “It was a black + white adventure fantasy, top-down, square tiles, fight monsters and so on. I really liked this game and I figured out that its file system was pretty simple, because when you win the game, you get a special power where you can change the world and you can change the individual squares on the map to be whatever you want… It gave me the idea to make a map editor for the game, so I could make my own maps and walk around them.”

Then only about 12 years old, he reached out for help finishing things off—first from his father and then from the game’s author. Impressed that Henry was hacking his game “for good instead of evil,” the author sent along a free colour copy of the game. “That was the first time I got paid in some way for something I’d built,” says Henry. “I think that solidified in my mind that I could do something with this, and I could actually make games for a living and I would enjoy it.”

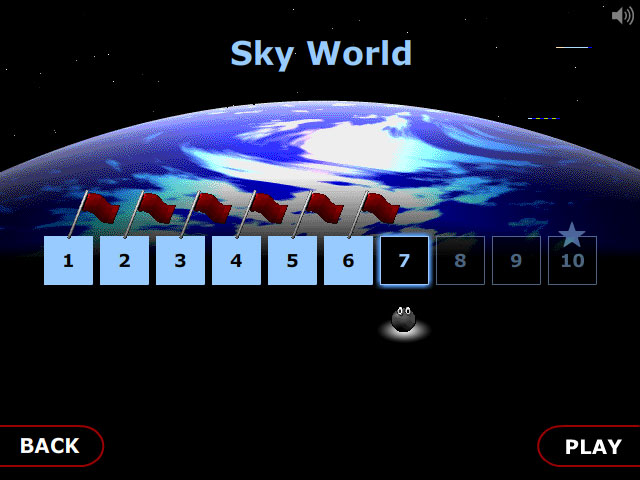

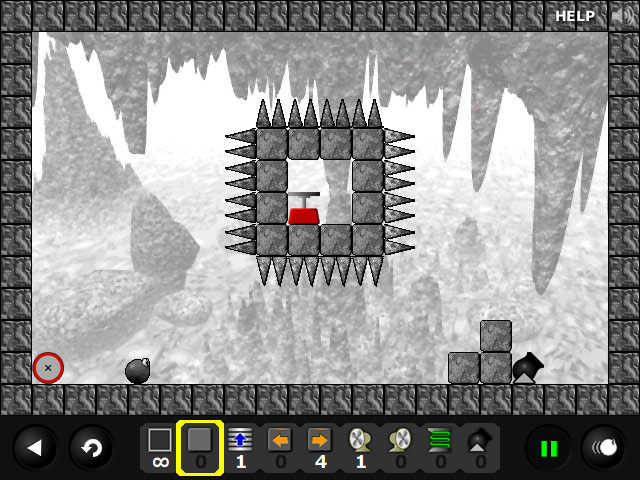

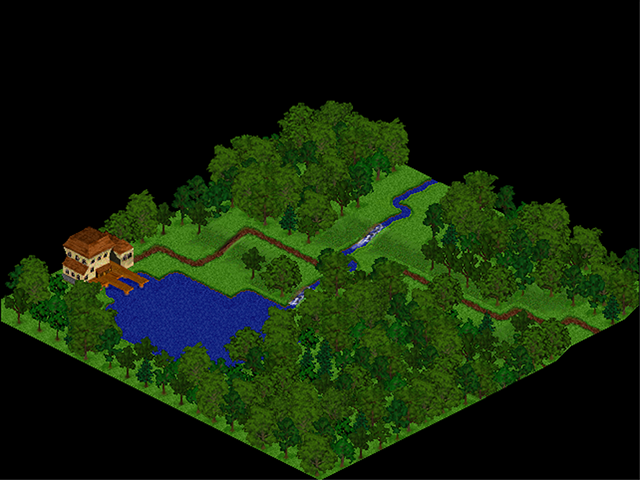

Squish screenshot

So, he set about making Squish, a puzzle adventure game. At first, he didn’t intend to sell it. But when his family relocated to Ottawa and he started learning the programming language C++ at Glebe Collegiate Institute, he quickly cobbled together enough knowledge to make a version of Squish that ran as a native Mac application, and posted a free demo on bulletin boards, websites and FTP servers.

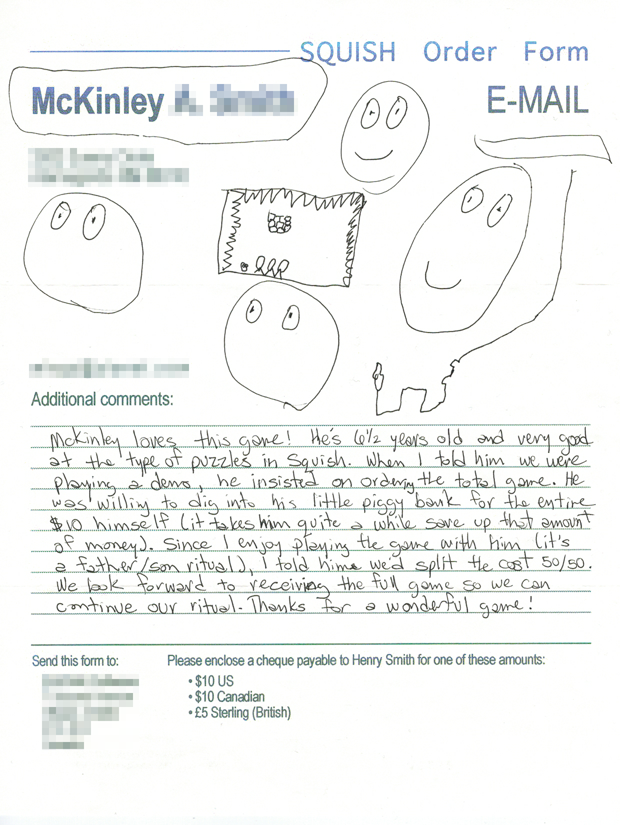

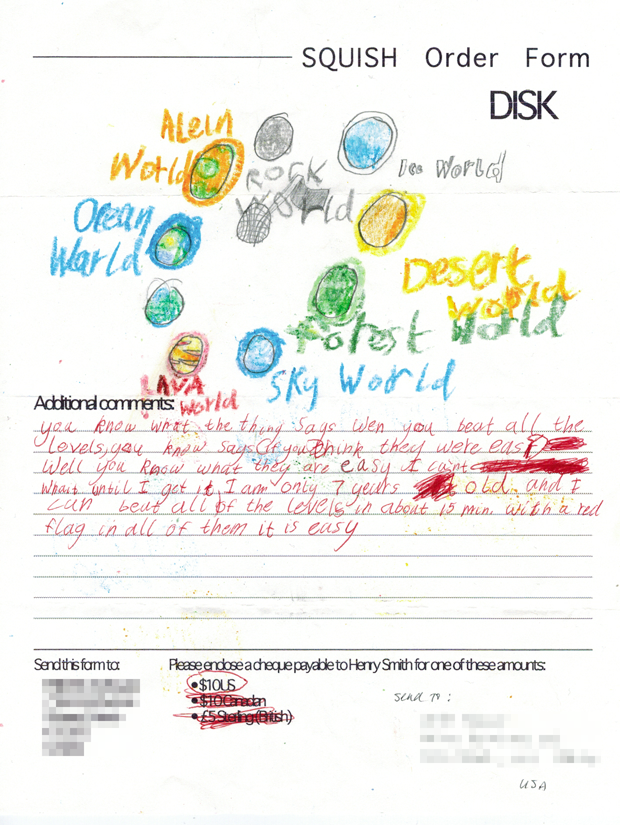

A few other Squish screenshots

Fans of the game promptly mailed in their $10 to order the full version. But the best part wasn’t the money. “I would get these personal letters from people who wrote, ‘I love your game! My six-year-old and I have been playing it. Here’s a picture he drew of Squish,’” says Henry. “It was awesome.”

Squish also attracted older players. Mac publisher Fantasoft Games got in touch and offered to take over publishing Squish. That meant no more handwritten letters in the mail, but it also enabled a wider audience and credit card transactions. “At its peak, I was making about $500 per month, which is an amazing amount of money for someone in high school,” says Henry.

Breaking the code

After graduating from Glebe in 1997, Henry enrolled in a Bachelor of Mathematics program at the University of Waterloo, with a focus on Computer Science. He entered the co-op stream, which meant that each four-month school term was followed by a four-month work placement.

Wanting to branch out beyond the school’s own placements, he found unusual alternatives for his co-op terms. One involved working from home on an indie game called Peregrine. It was a single-player fantasy role-playing game that “had a vague storyline to do with some gods in a world I’d created,” he says. “Everybody’s soul was linked to a star, and there was a special spy glass, and a lot of magic and swords and sorcery.”

Peregrine artwork by Daniel Smith

Once again, Daniel contributed artwork, and Henry learned a lot about what’s involved in making a game. One of the key lessons was that four months isn’t nearly long enough for a project of Peregrine’s scope. “I had to write programs in order to build the world of the game, as well as the game itself, and that took a lot longer than I thought it would,” says Henry.

As a result, the game was never completed. But it led to a major milestone in his career trajectory. While working on Peregrine, he launched a blog featuring his progress and Daniel’s artwork. Upon discovering the blog, “one guy made a fan site for the game, even though the game hadn’t come out yet,” says Henry. “That was one of the things that kept me going and knowing I was on the right track—having people who were interested in stuff I was doing even before I could get it out. That was cool.”

Irrational Games

In 1999, as his third co-op term approached, Henry and some fellow Waterloo programmers decided to branch out even further. They headed to Los Angeles for the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3). Henry hit the show floor, handing out as many résumés and demos as he was able.

The trip more than paid for itself. It led to a placement with Irrational Games in Boston, Massachusetts, which began as a co-op placement in 1999, but ended up leading to full-time employment and a break in his formal education, which lasted until 2002. “That was a great opportunity,” he says. “I was doing my dream job, pretty much, and I really loved Boston.”

Henry spent most of his three years there working on a game called The Lost, which was based on Dante’s Inferno. He recalls it as “a cool game,” but one that was somewhat behind the technological times, and it ended up being cancelled. Still, it was time well spent; he learned a lot, worked with a fantastic team and made connections with what would become a powerful company in the gaming industry.

“Irrational Games is now incredibly successful,” he says. “They went on to make BioShock, which is really popular. Now they’re working on BioShock Infinite, one of the most anticipated upcoming games.”

“Henry’s awesome. He’s a smart and talented games programmer—very clever. I’m so excited that he’s been successful in his first foray into indie gaming and I’m really looking forward to what he does next!” —John Abercrombie, Lead Programmer, Irrational Games

BioWare and beyond

In spite of how much Henry loved his time at Irrational Games, he eventually decided it was worthwhile heading back to Waterloo to finish his degree. So, with his work visa almost up, he did just that.

After graduating in 2004 with a BMath, he wound up in Edmonton, Alberta working for BioWare as a user interface programmer, primarily on a game called Dragon Age: Origins. Then, in 2009, ready for a change, he transferred to Montreal, Quebec to work with Electronic Arts, which had acquired BioWare in 2007.

“Working with Henry, I always found him to be energetic and full of new ideas to solve problems. He had a way of coming at a problem from a new angle, which often led to a novel solution.” —Trent Oster, Creative Director, Overhaul Games, Director of Business Development, Beamdog (formerly Executive Producer and Director of Technology, BioWare)

Let the gaming begin

Henry greatly enjoyed his time at BioWare. But one thing was never far from his mind: He wanted to get back to making indie games. When he had enough money saved up, he worked out a convenient departure date with BioWare (after completing his work on Mass Effect 3), and then took off on his own in the summer of 2012.

But first things first. Before launching into his games, he and his then-girlfriend of several years—the fabulous singer and Concordia University Masters of Anthropology student Sara Breitkreutz—spent five weeks travelling in Europe. The trip included a stop at his favourite place in Florence, Italy, by a church atop a hill, which is where Sara proposed (the two will be married this summer).

Henry and Sara, moments after their engagement, Florence, Italy, 2012

Then, freshly rested and newly engaged, Henry set about reviving his indie career. He put his initial idea for an ambitious for-profit iPhone game called Shipshape on hold, in favour of a shorter-term experimental project that would ease him into the swing of things and that he’d make available for free.

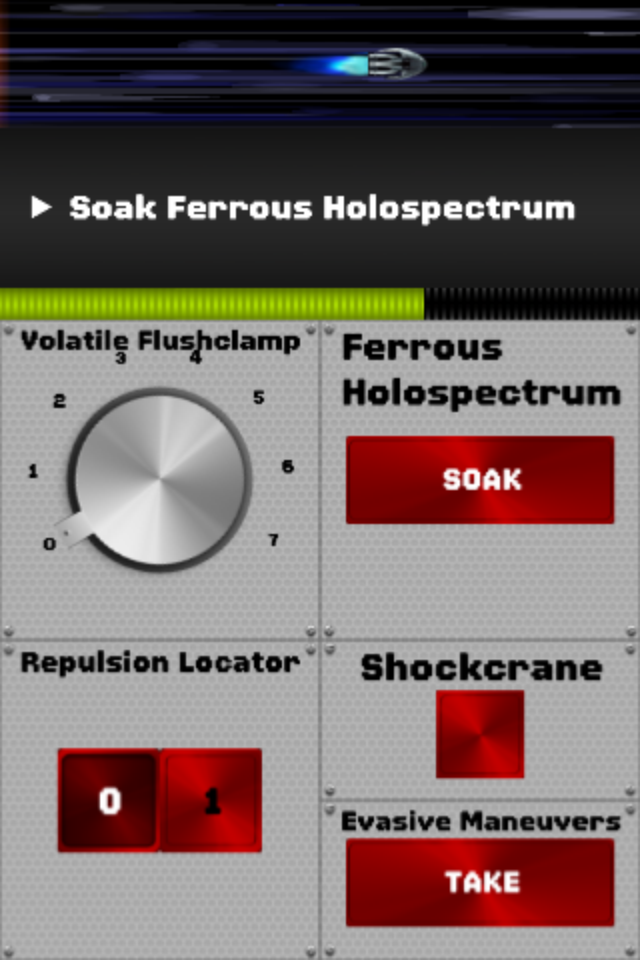

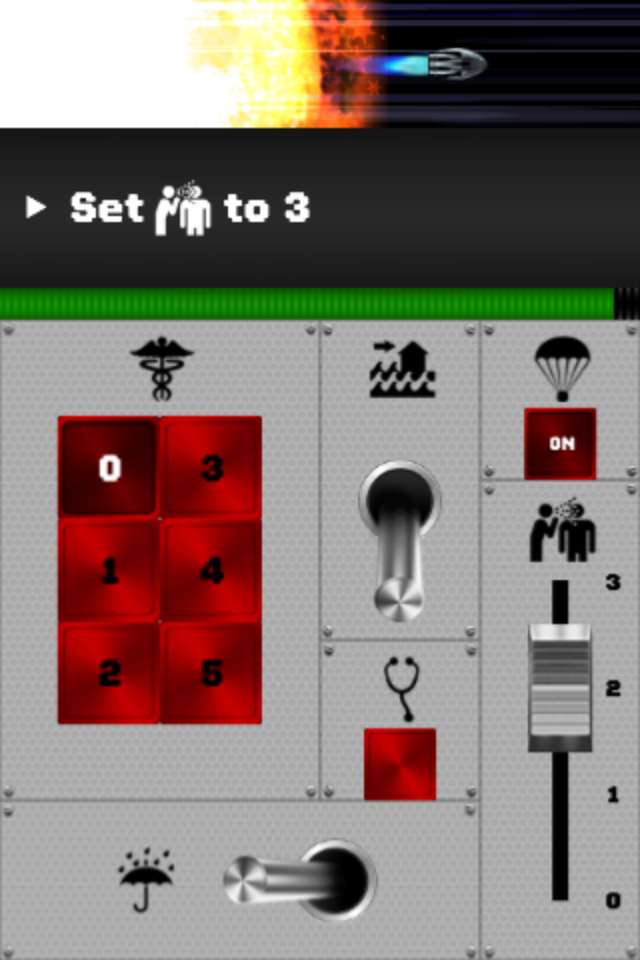

Spaceteam

Henry, who says his ideas “come from everywhere,” drew from a few specific sources for Spaceteam. There was the board game Space Alert; the digitally enabled folk game Johann Sebastian Joust; and the dream he had after seeing the short film Caine’s Arcade, a documentary about a nine-year-old boy’s cardboard arcade.

“I had a dream where my brother and I—it’s a dream, so it wasn’t really clear which brother it was—were wandering around this science fair in an old abandoned building. We sat down at one of the exhibits, which was kind of like the arcades from Caine’s Arcade. It was like a table arcade cabinet thing with two screens. One of the screens would flash text and instructions, and the other would have this really complex menu of options that you had to choose from. You had to find the option that matched the instruction on the other screen. I think I got the idea of what we were supposed to do, but my brother didn’t understand it, so I kept getting mad at him because he didn’t understand how to play. The user interface was terrible, but that gave me the idea to make a game like that, where one person would see something on the screen and the other person would have to respond to it.”

And so Spaceteam was born. Henry launched it in autumn 2012—to far greater acclaim than he ever anticipated. The game is nominated for a Nuovo Award at the 2013 Independent Games Festival (IGF), and received an honourable mention in the Excellence In Design category. He’s been invited to speak on a panel at IndieCade EAST in New York City, and is waiting to hear back on whether Spaceteam makes it into the Penny Arcade Expo (PAX) in Boston. (If this Penny Arcade comic is any indication, I think it’s safe to say they’re already fans.)

He’s also racked up a slew of glowing reviews and has gotten many exciting (and excited) tweets, including from the Star Trek Into Darkness editorial team, IGF Chairman Brandon Boyer and Wired columnist Andy Baio, to name a few.

Although Henry was surprised by Spaceteam’s success, he has a theory as to why it might have come about: because his game is so unusual. “Normally, in a game like that, everyone’s doing the same thing and competing with each other,” he says. “I wanted to make an asymmetric multiplayer game where people have different roles.”

It seems as though others wanted to see that, too. Case in point: this hilarious video of the guys at Giant Bomb playing Spaceteam. They were so into the game that they ran out of time for their usual review.

Shipshape

In between juggling media and speaking commitments for Spaceteam, Henry is gearing up for Shipshape, which he describes as “a sort of space game based on the board game Galaxy Trucker, with elements of Star Control II and Escape Velocity thrown in.” He plans to focus on creating an accessible touch user interface that’s as simple as it is smart.

Part of the reason for this is to create a great game that users will enjoy. But he is also clearly excited about playing a role in changing the way people perceive and interact with video games. In particular, he’s interested in how they can facilitate education. “I think more and more people are going to play games, and that they’ll be integrated with life and school and work in ways that aren’t necessarily obvious—that are more behind the scenes and in the background—but that are still significant and beneficial.”

For the moment, though, he’s content to pursue Shipshape and take life as it comes. The way he sees it, “if I can sustain myself by making indie games, I’ll keep doing this for the foreseeable future, because this is my ultimate dream.”

Sara and Henry near her great-grandparents’ homestead, rural Alberta, 2012

By all accounts, Henry is at the start of a very exciting career—one that I expect will play an influential role in the industry. After all, he got me hooked on Spaceteam, and I’ve never been one to play video games. But more importantly, he has the courage to attempt to live his dream, and the talent, skills and intelligence to make it a reality.

Expect great things from this one.

* * *

For the latest on Henry, visit SleepingBeastGames.com, ‘Like’ his Facebook page, follow along on LinkedIn and @hengineer on Twitter, or email [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Very impressive! Fortunate to have crossed paths with this impressive individual.

… And Amanda – another great write-up! Thanks for enlightening.

Best, Andrew

Thanks so much, Andrew! Agreed – we’re lucky Henry hopped the pond and went to GCI. I’m sure there’s a lot more great stuff to come from Henry… Stay tuned.

I was gutted when Peregrine didn’t come out. Last time I looked a few years ago I couldn’t find anything about it on the Internet. I just thought about it again the other day and lo and behold what I find on the internet this time! Thanks for the great article!

Cheers,

Graham

Graham, so glad you found, and enjoyed, the article! Henry is currently running a campaign to raise funds so he can keep making free games – check it out: Spaceteam Admiral’s Club.

Wow thanks Graham, I had no idea people still remembered Peregrine. It was much too ambitious but I learned some invaluable lessons. I still want to do something in that world, but it probably won’t be the game I envisioned 15 years ago…

– Henry