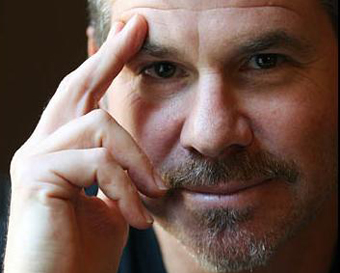

Richard J. Lewis, filmmaker-househusband

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: November 15, 2018

“I think the most important part (of being Canadian) is the tradition of music and literature that we’re steeped in.”

About 15 years ago, I first saw a haunting Canadian film called Whale Music. It’s a profoundly moving piece about a deeply complicated musician played by Maury Chaykin, and it instantly became a favourite of mine.

In 2010, both Maury and Paul Quarrington, the author of the book upon which Whale Music was based, passed away. I hadn’t followed Paul’s career, but have always been a huge fan of Maury’s. When he died on July 27—his 61st birthday—I felt compelled to write a tribute, both to Maury and the film.

To my surprise and delight, Whale Music writer/director Richard J. Lewis saw my post and fired off a kind comment a few weeks later. And that was the end of that.

Until a few months later, when I’d launched this website, seen Richard’s latest film Barney’s Version and realized that I probably still had his email address from when he submitted his comment. I approached him for an interview, and within a matter of hours, he had replied and enthusiastically agreed to be part of something that was “exalting Canadians.”

For Richard, one of Canada’s strongest selling points is its artistic achievements. He speaks with pride about the many great works that have come from a range of Canadian artists. In my opinion, Richard is among that group. His latest effort, a film adaptation of the late Mordecai Richler’s acclaimed novel Barney’s Version, is a fine addition to the growing canon of quality Canuck creations. It’s up for 11 Genie Award nominations, including best picture, best director, best adapted screenplay, best actor (Paul Giamatti as Barney) and best actress (Rosamund Pike as Miriam).

With a distinguished career in film and television—among many other things, he spent several years writing, producing and directing CSI: Crime Scene Investigation—it’s easy to see how far Richard has come. I was more interested in how he got there.

Competing interests

Richard knew from a young age that he wanted to be involved in the arts. But before art, there was tennis.

The sports prodigy grew up on the courts in Toronto, Ontario. He was the provincial tennis champion by age 12, the national champion by age 14. His days were grueling: up in the wee hours to squeeze in a two-hour training session before school; race off to class; bus back to his coach for an afternoon workout; cram in some homework; fall asleep. “Then I’d get up and do it again,” he says. “That was life.”

While he was in the throes of tennis, he discovered his friend’s Super 8 camera. He was immediately drawn to the world of filmmaking, and started making movies with his Forest Hill Collegiate Institute (FHCI) classmates. He even tried to sell his teachers on accepting films in lieu of essays; the pitch failed, but Richard ended up making the movies anyway and submitting them with his papers. One of his first films was a black and white short based on Edgar Allan Poe’s story The Tell-Tale Heart, which won first place in a local student Super 8 competition.

Richard stayed with tennis throughout his teens. But it was becoming increasingly clear that his heart was somewhere else. Toward the end of high school, he attended the renowned Harry Hopman Tennis Academy (now Saddlebrook Tennis Academy) in Florida—a boot camp on par with the IMG Bollettieri Tennis Academy where Andre Agassi trained. “I knew I was different from the other guys because they were just obsessed (with tennis) and really myopic,” says Richard. “They were just looking at tennis as their life, and I really couldn’t imagine just playing tennis as my life.”

Still, Richard was pragmatic. He stuck it out for the time and took advantage of his athletic prowess to land a tennis scholarship at Chicago’s Northwestern University, where he enrolled in a liberal arts program. Once he was there, soaking up lectures on literature, drama and philosophy, there was no denying where his passion lay. He fell in with the theatre crowd and discovered a penchant for acting, taking on roles in countless school productions.

By his third year, he was dropped from the tennis team. But it was more of a relief than anything else. By that point, he says, “I hated tennis. I was sort of defined by tennis my whole life.”

Lifting the curtain

When he graduated from Northwestern in 1984, he was ready to redefine himself. He spent a couple years working as a theatre actor in Chicago, before lifting off to explore other sights. In the late 1980s, he made his way further west and completed a Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Southern California (USC).

Upon graduation, the industrious artist was ready to take on a new film project. Always a fan of his homeland’s creations, he knew where to turn for inspiration. “I was looking for Canadian material,” says Richard. “I stumbled upon a book called King Leary by a writer named Paul Quarrington, and so I called him up.”

The two men arranged a meeting, and Richard quickly sold him on his take of the novel. They spent the next few months collaborating on the screenplay, which ended up being optioned to several people in the industry. The film itself never panned out, but Richard and Paul’s friendship was a done deal.

Whale Music

When Paul’s next novel Whale Music was optioned by Alliance Films, he put in the good word for Richard to direct. “I sent them a short film that I had made for BC Hydro,” says Richard. “They basically hired me to adapt and direct the movie.”

Richard on the set of ‘Barney’s Version’

Whale Music was released in 1994 to great acclaim. It was nominated for several Genie Awards, including best picture and best director; Maury Chaykin won the Genie for best actor. “Whale Music… shaped my career,” says Richard. “It’s hard to make independent movies where you have full control of the reigns anymore… But back then, I basically made that film; that is my movie from beginning to end, and that was a really great experience, to be able to do that.”

After Whale Music, Richard found work directing the Canadian television show Due South, starring Paul Gross and Callum Keith Rennie. He hit it off with the show’s creator, Crash writer/director Paul Haggis, and soon found himself directing for Paul’s television programs south of the border. Richard’s work on Easy Street, Michael Hayes and Family Law eventually led to a long-term gig writing, directing and producing for CSI: Crime Scene Investigation as of 2000. He’s been living in Los Angeles ever since.

Strong Canadian roots

Richard’s move to the United States hardly came as a surprise. “I always wanted to be based in Los Angeles because I feel that if you want to make movies, you go to where they make movies,” he says. But he’s still excited about the prospect of collaborating with Canadians and drawing on their talent.

“It’s fortuitous and also industrious to take advantage of being Canadian,” he says. “I’ve been very lucky in terms of the type of material I’ve been able to mine as a Canadian. There are two award-winning novelists—probably two of the finest novelists of my time—(whose work) I’ve made into movies, Whale Music and Barney’s Version. I might be an ex-pat in the fact that I don’t live in Canada, but my sensibility doesn’t have anything to do with being an ex-pat. My sensibility still reveres great Canadian work.”

Watching the monitor on the set of ‘Barney’s Version’

Barney’s Version

Richard had long counted Mordecai Richler’s novel as one of Canada’s greatest works. He spent six years approaching Alliance’s Robert Lantos—who produced Whale Music and Due South, and who owned the rights to Barney’s Version—about directing the movie. Eventually, Richard got tired of getting “the quick slip” from Robert. While still working on CSI, he took it upon himself to draft a spec version of the screenplay for Barney’s Version.

In describing the adaptation process for that script, Richard says he came at it from the top down; he considered everything in the novel, and then started pulling out the parts that weren’t necessary for the film. “You have to be judicious in your editing, in terms of what you want to put in and what you don’t want to put in,” he says. “I find that every scene wants to have some kind of function towards the whole; it has to have a function towards the theme or the plot in general. If doesn’t have that, it doesn’t belong in the movie.”

Toward the end of 2006, Richard presented Robert with his draft of the screenplay. At first, the producer was thrilled and immediately set up a deal with Richard to write and direct the film. Then, he reconsidered the writing portion of their deal. Many writers had already tried their hand at adapting Barney’s Version, including Mordecai himself. Richard’s take was the best to date, having solved many of the problems that hadn’t been overcome in previous drafts. But ultimately, “Robert wasn’t prepared to go to camera with (my version),” says Richard.

Writer Michael Konyves was brought on board, and it was his draft that ended up being shot. “Michael’s writing was terrific,” says Richard. “I conceded that, in the end, his script would make a better film than mine.”

Finding the right voice

Having seen the film twice and speed-read the novel in preparation for this interview, I thought Richard did an excellent job of capturing the tone of the book. I was, however, struck by the absence of Barney’s voice in the film; it’s a much more objective telling than the very personal account written by Mordecai.

I asked Richard whether there was any thought given to incorporating Barney’s voice via narration. As it turns out, voiceover narration was a part of his adaptation. It was nixed because the rest of the filmmakers thought the movie would be better served without it. But Richard has strong opinions on that decision.

“There is a bias in (the industry) against voiceover narration,” he says. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve sat in meetings and heard producers and development people go on and on about how they hate voiceover, calling it a device… My thinking is that if it can embellish the material, it should be used.”

Richard attributes the anti-voiceover sentiment to a slew of films that have misused the technique. Rather than employing it to complement or elevate the visuals, he feels that too many movies have made it redundant by simply stating what the viewer is already seeing onscreen. He cites a number of films, including Little Big Man, My Life as a Dog, Easy A and Juno, as evidence that voiceover can be used to great effect.

Directing Dustin Hoffman on the set of ‘Barney’s Version’

At the end of the day, he still wonders whether it was a mistake to remove narration from Barney’s Version. “When you make a movie with Dustin Hoffman and Paul Giamatti, there’s more people involved in steering the ship,” he says. “But ultimately I think I missed Richler’s voice in the final film. I might have added some voiceover just to preserve some of the novel, and I think it could have given more scope to (Barney’s) memory. I feel like it would have given more resonance to the title of the movie.”

Casting about

There’s another topic about the adaptation that gets Richard going. I asked him about the decisions to replace Toronto with New York as a locale, and to cast non-Canadians in several of the lead roles (Giamatti and Hoffman are American; Pike and Minnie Driver are British). As far as the first question, he explains that he decided very early on to make the film more universal. But he makes it clear that the movie’s main setting is absolutely faithful to the novel. “The film is truly set in Jewish Montreal,” he says. “That was not compromised in the film one bit.”

Directing Paul Giamatti on the set of ‘Barney’s Version’

The question of casting took the volume of our conversation up a notch—not out of hostility, but simply out of Richard’s strong feeling that divisiveness has no place in art. He emphasizes that all casting choices were made based on who was best for the role, regardless of nationality. In fact, Canadian Jim Carrey was briefly considered for the role of Barney, but it was decided that he didn’t have the proper ethnicity for the part, and that it would be harder to convincingly pull off Barney’s 40-year age range with him.

“Here’s the point: What’s the difference who plays the lead in this movie?” asks Richard. “Paul Giamatti’s not Canadian and he’s not Jewish. There’s two infractions right there. But is he true to the Barney in the novel? I truly think so… It’s so silly when we start making divisions and factionalizing people… These distinctions are really important to Canadians. ‘Is it Canadian?’ Especially with art. It gets me really riled up because there’s only two distinctions in art that I really care about. Is it good art or is it bad art?”

He also makes a point of naming the many Canadians who do appear in the film, including Scott Speedman, Bruce Greenwood and Rachelle Lefevre in principal roles, as well as Paul Gross, Atom Egoyan and David Cronenberg in cameos.

Stolen moments

Indeed, the casting of Barney’s Version was very well done. Each one of the actors gives an excellent performance, and stays true to the essence of their character.

When watching the movie, I was impressed by the space Richard gave his actors; many pivotal moments are captured in one shot, as opposed to cutting away for close-ups. Given his evident sensitivity to the actors’ process and appreciation for their performances, I wasn’t surprised to learn about Richard’s theatre background.

“As an actor, there’s nothing better than letting the take play out,” he says. “What you’re looking for is the moment in a scene, there’s always some moment… If you’re trying to find that and you start dividing your scene up into little pieces, then it becomes very elusive to find that moment. But if you allow the scene to play out and you give the actor more of a theatre approach to it, (they’re) usually are able to go inside the scene and find that elusive moment that you really want.”

Creating life, creating art

These days, the moment Richard really wants is the one he spends at home in Los Angeles with his wife, Emily Christie, and their nine-month-old son, Leo. (His 11-year-old daughter, Emily Lewis, lives in Toronto with her mother.) He’s relishing the experience of being a “househusband.”

But he does have a number of film projects in development for further down the road, when his son is a bit older. As much as he loves having extended time with his family, creating art isn’t something he could give up for good. Ever since he discovered his artistic streak as a high school student in Toronto, he knew it was a fundamental aspect of who he was.

“I think the most important part (of being Canadian) is the tradition of music and literature that we’re steeped in,” says Richard. “Growing up in Canada, and being educated in Canada, (art) sort of seeps into your pores and never goes away. It always feels right to come back and do projects in Canada.”

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Fascinating article, Amanda. I’ve been such a fan of Richler’s work and especially Barney’s Version, so I couldn’t wait to gobble up Richard J. Lewis’ perspective on the film adaptation. And yes, particularly intrigued about the narration part… Interesting stuff. I think I have to agree with Lewis’ take here; I’m not so convinced that voice narration in this case would’ve been detrimental – in fact, it would’ve been a great way to showcase the depth of the humour and poignant musing that Richler created through Barney. But I digress – the film is still a success and, although I was terrified to see it in fear that it would ruin my favourite book, I enjoyed that it was a new lens through which I could see the story in a summarized way.

And… Wasn’t that Denys Arcand I saw playing the part of the waiter?

Great job Amanda, and thanks for digging deeper and sharing this info with everyone. Keep it coming…

Camille

Merci Camille! It was really helpful to get your insight prior to my interview, because I had only had the chance to zip through the novel before speaking with Richard, whereas you have in-depth knowledge of it.

Yes, it was Arcand! He’s the only one of the featured Canadian directors I wouldn’t recognize without someone like you pointing it out 😉 Egoyan and Cronenberg totally cracked me up, especially Cronenberg.

Mr. Richard J. Lewis, what a surprise! We have a small foreign film venue here in Toulouse, where I go often, and I saw Barney’s Version in this month’s film review (great reviews but I haven’t seen it yet). When I saw who the director was, well, I thought, I think I know this guy!! I’m going this week. I’m so happy for you, congratulations and all that, from a childhood buddy.

Thanks for taking the time to comment, Cameron – glad you found the site. Enjoy Barney’s Version!

Great interview. ‘Barney’s Version’ is one of the Canadian films I revisit most often, so it’s nice to read Lewis’ own take on the adaptation. I really like how the film opens up the book and makes it more universal, yet keeps a distinctly Canadian quality.

Thanks, Pat! Glad you enjoyed it! I thought it was interesting to hear Richard’s experience of how the final product came to be.

BTW I love what you’re doing on Cinemablographer to highlight Canadian film. Keep it up! 🙂