Richard Weber, Arctic and polar explorer

“Youth are the future leaders of the world, and they need to realize that climate change is serious. We want to introduce them to the Arctic through a scientific, Outward Bound type of educational program.”

Richard Weber was born in the right country; he loves the cold.

“Cold doesn’t bother me as much as hot,” he says. “I don’t like the heat. You remove all your clothes and you’re still hot. Then what do you do? If it’s cold, you just put on more clothes or generate heat by moving.”

Gearing up and getting moving is something Richard does exceptionally well. He was one of the first two Canadians to reach the North Pole on foot (with teammate Brent Boddy in 1986), the first person to reach the Pole from both sides of the Arctic Ocean (Canada and Russia), and holds the world records for number of treks to the Pole (seven to date) and fastest time from Nunavut’s Ellesmere Island to the North Pole (41 days).

His adventures have taken him on more than 50 Arctic expeditions, as well as several journeys to the South Pole. In 2009, he completed the trek from Hercules Inlet, Antarctica, to the geographic South Pole in just under 34 days—a record at the time. He was accompanied by fellow Kickass Canadian Ray Zahab and Canuck Kevin Vallely as part of an impossible2Possible expedition.

Richard skiing to the South Pole

Jay Ankersmit, Director of the Ottawa High Performance Centre (OHPC), recommended Richard for this website. Having treated Richard, Jay is familiar with his incredible stories and was keen to have them shared with as many people as possible. “When it comes to Arctic adventures, there’s no greater storyteller than Richard,” says Jay.

He’s right. Richard is widely considered the go-to resource on Arctic and polar exploring, and has made a career of leading kindred spirits through Canada’s icy plains and snowy terrain. On top of that, just to make sure he stays cold enough when not leading chilly expeditions, Richard—along with his wife Josée Auclair (an outstanding adventurer herself) and their sons Tessum and Nansen—operates Arctic Watch Lodge, a world-class beluga whale observation site that “offers hotel-like accommodations in a remote Arctic setting.”

But none of this would have been possible had Richard never stepped into his first pair of skis at age two…

Winter wonderland

Born in Edmonton, Alberta, Richard’s family moved to Ottawa, Ontario when he was one year old. His father had been a successful climber and skier in Switzerland, and was keen to introduce his son to the wonders of winter sports.

Richard was a natural skier. By six, he was cleaning up in his age category at the races. He made the national cross country ski team in 1977, and represented Canada in the 1977, 1979, 1982 and 1985 World Cross Country Ski Championships (now the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships). Over the course of his career, he picked up 20 national skiing titles, as well as the gold medal for biathlon in 1983.

It was while on the national team that he met and fell in love with fellow skier Josée Auclair. Still competing on Canada’s behalf, the two headed to the University of Vermont on ski scholarships. Richard graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1985, and Josée finished up soon after with a degree in Botany in 1986. That was also the year they wed. And the year of his first expedition.

“An American colleague of my father’s was planning an expedition to the North Pole that would go through the Northwest Territories, and he was looking for a Canadian who could ski,” says Richard, referring to Arctic explorer and advocate Will Steger. Hans put his son in touch with Will, and Richard was quick to accept the offer when it came.

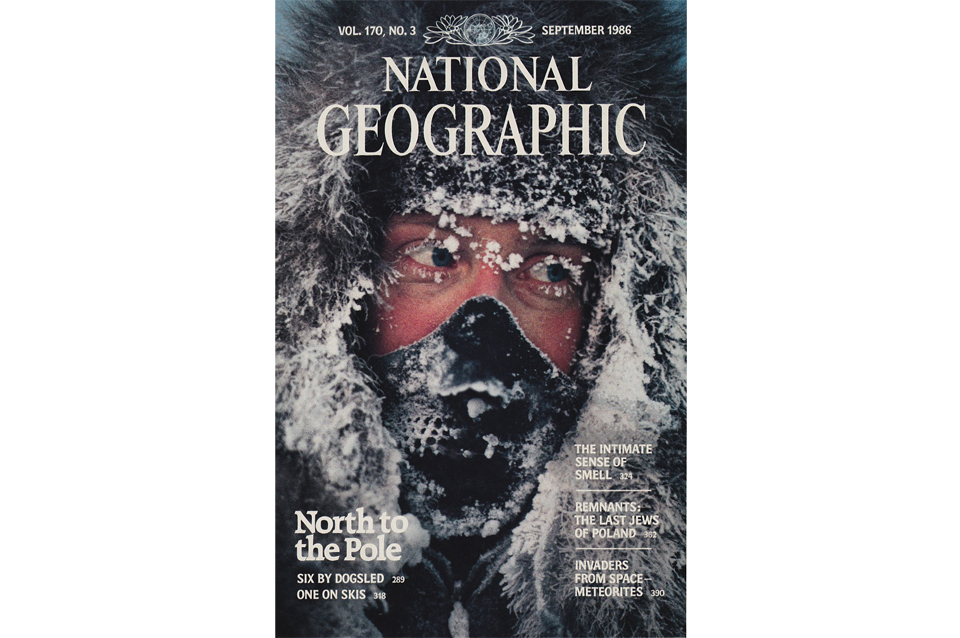

The trek was a big deal. Not only did the Will Steger International Polar Expedition mark the first time Canadians reached the North Pole on foot, but it marked the first time a woman had completed the journey—American Ann Bancroft. National Geographic ran a cover story on the expedition in its September 1986 issue.

Brent Boddy on the cover of National Geographic, September 1986

A series of firsts

After successfully completing the mission, Richard was hooked on exploring. He’d had his sights on skiing for Canada in the 1988 Winter Olympic Games, but, he says, “I started doing expeditions and that was a lot more fun.” He promptly went on to achieve several more polar firsts.

In 1988, he joined the Soviet-Canadian Polar Bridge Expedition and became the first person to reach the North Pole from both sides of the Arctic Ocean. At the end of the trek in 1989, be became the first to accurately stand at the Geographic North Pole (first GPS to register “90” north).

In 1993, Richard and Josée organized and led the first commercial trek to the North Pole.

In 1995, Richard and his travel companion, Dr. Mikhail (Misha) Malakhov, completed the first unsupported expedition to the North Pole and back—an achievement that has yet to be repeated. “That trek was no doubt my best memory from my expeditions,” says Richard. “It was an amazing expedition. Amazing teamwork, unbelievably tough.” For more on Richard and Misha’s account of the journey, pick up their book Polar Attack.

In 2006, Richard and fellow explorer Conrad Dickinson became the first to trek to the North Pole using snowshoes exclusively.

On Richard’s latest expedition to the North Pole in 2010, he was accompanied by his eldest son Tessum. With that journey, Tessum not only became the youngest person to complete the trek (he was 20 at the time), he also became part of a three-generation dynasty of North Pole adventurers; his Swiss grandfather flew to the Pole in 1968 as part of a scientific expedition.

Richard at the North Pole

Keeping watch

In between all these amazing adventures, Richard and Josée started Arctic Watch Lodge, “Canada’s most northerly lodge, located in Cunningham Inlet on Somerset Island in Nunavut.”

Up and running since 2000, Arctic Watch shares the landscape with a range of animals, including muskox, polar bears, Arctic foxes and birds, as well as thousands of beluga whales. The wilderness resort offers a safe, cozy place from which to discover the Arctic, and is just a 4.5 hour private charter flight from Yellowknife, N.W.T.

“(Arctic Watch) was Josée’s idea,” says Richard. “We started guiding, doing ski trips and kayak trips in the Arctic, and she thought a lodge would be a better idea, so she suggested we build one.” When the spot in Cunningham Inlet came up for sale, the couple knew it would be the perfect spot not only for their business, but to raise their children. “(Tessum and Nansen) have been going to the Arctic since they were little kids,” he says. “It’s taught them independence, resourcefulness and much respect for the environment.”

From left: Nansen, Josée, Tessum and Richard

In addition to Arctic Watch, Richard and his wife run Weber Arctic, the world’s top polar training, guiding and outfitting company. They sell custom polar products, including ski bindings, mukluks, wind suit jacket and pants, sleds and tents, and are well established as the best in the business when it comes to providing polar gear. In fact, the Canadian Forces recently tested out the Weber Polar bindings to see how they suited the soldiers during winter training.

Richard and Josée also offer homemade food for polar expeditions, jam-packed with as many calories as possible. “You need really dense, high calorie stuff,” he says. “But it’s kind of nice if it tastes good. So we have this polar pâté that we make that’s has more than 700 calories per 100 grams, deep-fried double smoked bacon, these really rich chocolate truffles, that kind of thing.”

Warming up to take action

Richard and his family are proud to outfit some of the world’s top adventurers, and to expose tourists to the Arctic through their Nunavut resort. But their bigger-picture goal is to bring awareness to the effects of increased human activity in the Arctic, and to do everything they can to protect the beluga whales in the area.

As a starting point, Arctic Watch Lodge was built and is operated with the environment kept top of mind. Their airstrip was designed to decrease impact on the surrounding environment, they maintain a system of trails to prevent land scarring, and sewage and garbage are handled in the most environmentally friendly way possible. They also keep visitors to a minimum so as not to disturb the local ecosystem.

“The climate’s really changing quite dramatically,” he says. “It’s just plain warmer and dryer. The permafrost is receding. Two summers ago we had mosquitoes. There’s never been mosquitoes in that part of the Arctic, but we had mosquitoes.” Beyond the bugs, the Webers have spotted birds, such as sparrows and sandhill cranes, that aren’t native to the area, and seen the number of polar bears mushroom, which they attribute to diminished ice in the northwest passage on Somerset Island.

And Richard says they’ve started seeing injured beluga whales over the past couple of years. Some have what appear to be propeller wounds, or even gun wounds. One turned up with a rubber inner tube around its body. “We don’t know exactly how the climate changes have affected the whales, but there’s a lot more ship traffic than there used to be, and that means more human activity and interaction with the whales… We also don’t know whether the whale population is changing; when there are thousands of whales swimming around, you can’t count them with your bare eyes. We feel the whales should be monitored and, ultimately, protected.”

Richard at Arctic Watch

Arctic Watch Beluga Foundation

From the mid-1970s until about 1999, scientists were on site to study the beluga population in the Arctic. Richard is determined to bring science back into the equation, so that he’ll have a stronger leg to stand on when it comes to protecting the whales and the region’s ecosystem. Together with an organization in the United States, he established the Arctic Watch Beluga Foundation (AWBF) a non-profit corporation whose mission is “to ensure a future for the Belugas of Cunningham Inlet through supporting scientific research and education at Arctic Watch.”

The Foundation will support two programs: original scientific research in Cunningham Inlet; and a program for high school students to experience the Arctic wilderness and participate in meaningful research. “Youth are the future leaders of the world, and they need to realize that climate change is serious,” says Richard. “We want to introduce them to the Arctic through a scientific, Outward Bound type of educational program.”

The educational component of the initiative is set to launch in the summer of 2012. It will start with a two-week program for youth worldwide, although the focus will be on Canadian students, including Inuit youth from Nunavut.

With regard to the scientific research, he expects that it will produce “real numbers” that will determine whether or not the whale population is diminishing. Ultimately, he hopes that the area will be declared a sanctuary for the whales.

Hitting his stride

Richard’s incredible contributions in the Arctic and on both Poles have earned him a number of honours, including: the 1989 UNESCO Fair Play Award; 1989 and 1996 Russian Order of Friendship of Nations; 1992 Canadian Confederation Medal; 1993 Russian Medal for Personal Courage; and both the 1994 and 1996 Canadian Meritorious Service Medal, which made him the only person to be awarded the medal more than once.

Between those impressive distinctions, and his large collection of athletic hardware, Richard is one well-decorated Canadian. But his focus is simpler, and more humble, than racking up medals. As far as expeditions go, next up is a trek to the South Pole in November 2011. He will lead four clients on a 35-day ski to the Pole and a 14-day kite ski back. As for Weber Arctic and Arctic Watch, his goals are to protect the whales, to safeguard Canada’s Arctic wilderness and to stay cold.

These things go hand in hand. And they couldn’t be in more capable ones.

* * *

To keep up with Richard’s adventures, ‘Like’ the Arctic Watch Facebook page and visit weberarctic.com. You can also check out his LinkedIn profile, or email [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians