Clara Hughes, humanitarian-adventurer-athlete-nature lover

“I’ve been reminded by so many people that I’m not alone in the struggles I’ve had, and I think that matters. As human beings it matters to know you’re not alone in this.”

In 2015, Clara Hughes spent 139 days hiking the Appalachian Trail. It was a self-supported trip that covered more than 3,500km, stretching between the trail’s southern terminus on Springer Mountain in Georgia and northern terminus on Mount Katahdin in Maine.

She made the trek over a period of several months, fitting in legs around work and other commitments. Hiking between six and 12 hours each day, she lugged all her gear, food and supplies, filtered her own water, and made and broke camp. Her husband, Peter Guzman, joined her for the first third of the trip, but the rest she did on her own.

By the time she reached the final stretch of the trail at the base of Mount Katahdin, only about an hour from the end, she didn’t feel the need to climb to the top. “I didn’t care if I finished or not,” she says. “I didn’t need to go up the mountain because the trip wasn’t about harvesting miles and being able to say I’d hiked a 3,500km trail. It was about every day I created during the hike.”

It’s taken Clara most of her life to reach that mindset—to be able to value the process and not feel the need to be validated by external landmarks or successes.

For many years, decades even, she was mainly known to the outside world as a champion athlete. A former competitive speed skater and cyclist, she is a six-time Olympian and the only person to have won multiple medals in both the Summer and Winter Olympics (including gold and silver in 2006).

But those achievements, as incredible as they are, don’t define her. And she doesn’t want others to define her by them, either.

“I think the Olympic medals are almost a metaphor for everything,” she says. “We are very much a consumeristic society and it’s deeply ingrained in every person form birth, I feel like, to have all this stuff. The focus is on looking a certain way and finding everything outside of yourself; we don’t really, for the most part, look within for fulfillment.”

Clara acknowledges that she herself used to think that way. She looked to the Olympics and her many medals to cure, or at least numb, the tumult she felt inside. It was only after years of missteps and painful lessons that she understood: Winning “isn’t going to fulfill me if I’m a broken human being and have a very linear and shallow approach to what I do.”

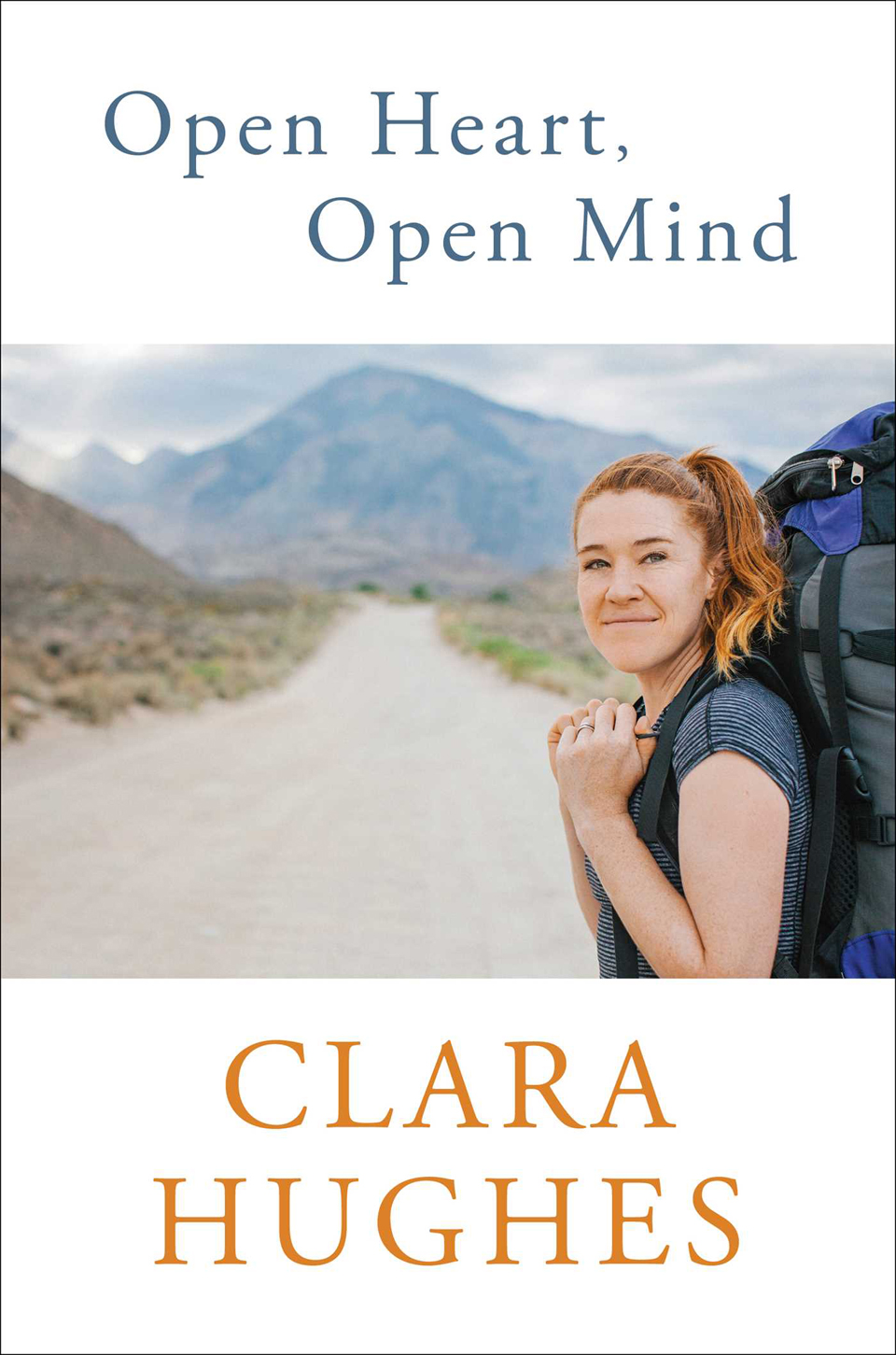

Those are shockingly honest words, especially from such a public figure. But it’s precisely because of her status that she wants to share the truth, and why she bares so much of herself in her memoir, Open Heart, Open Mind, released last year by Simon & Schuster Canada. She wants to shatter the illusion that she, or anyone, belongs on a pedestal.

Clara’s book recounts in great detail her upbringing in Winnipeg, Manitoba, which involved dealing with a verbally abusive alcoholic father and the related feelings of near-crippling self-loathing, unworthiness and depression. Throughout its pages, she remains raw and honest about drinking and using drugs, binge eating, starving herself and acting out.

She recounts how her life changed course after she famously watched a televised Gaétan Boucher speed skate in the 1988 Winter Olympics and knew, at 16, that she too would one day skate for Team Canada. But rather than becoming a healing path, athletics offered another means of escape for Clara. She hurled herself full-force into decades of trying to ride, run, skate away from the emotional pain she suffered.

It never worked.

“I come from a family history of addiction and health issues and I was terrified,” she says. “I really thought that if I won (Olympic medals) and succeeded, it would make all this crap I was putting myself through and these environments I was putting myself in… that it would somehow make it all worth it and I would feel something good for the first time.

“The first Olympics I went to, I was really messed up; I was not a functional person. Everything on the outside seemed okay but I wasn’t admitting things to myself because I didn’t know how to handle what was going on inside.”

After that “first Olympics,” the Atlanta 1996 Summer Olympic Games, where she won two bronze medals for cycling, Clara says she “cracked completely.” Her pace of life—chasing the fastest speeds she could to try outrunning what followed her everywhere—was unsustainable.

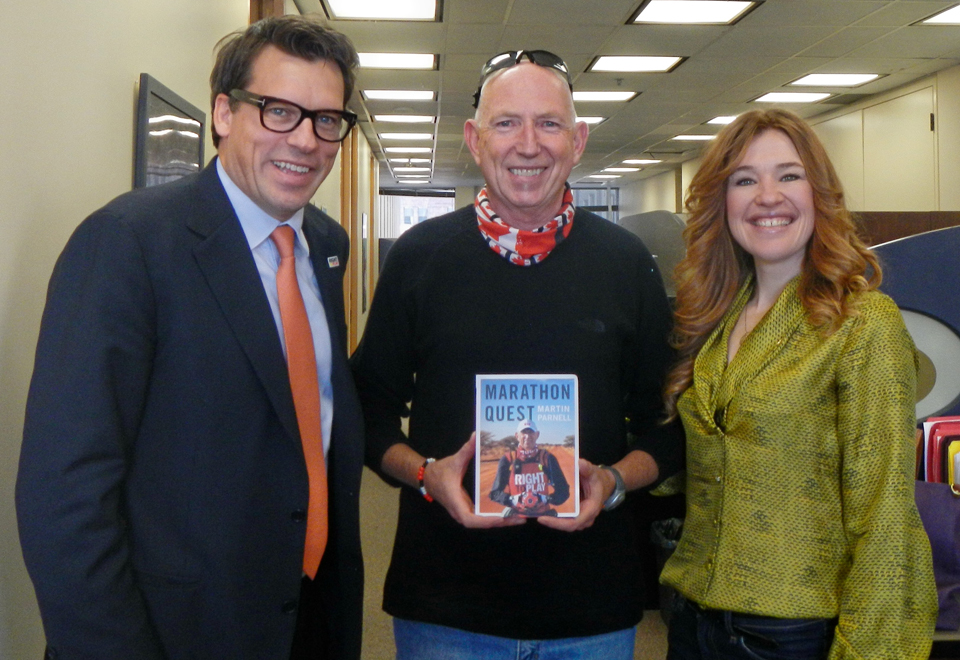

“I think Clara is one of the top Kickass Canadians. She has used her success in the world of sports to bring attention to areas such as children’s needs, mental health and First Nations issues.” —Martin Parnell, Kickass Canadian, Right to Play honorary athlete ambassador

On the podium at the 2002 Winter Olympics for her bronze medal in the women’s 5000m speed skating; Photo: Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

“Ripples on the surface of life, produced by unsuspected springs…”

Clara has no interest in fame or the fuss that comes with it. When she hiked the Appalachian Trail, she didn’t mention her sporting background to the people she met along the way; she went only by her trail name, Redfeather, and found it to be “a really impactful and freeing thing to not be known.”

At the 2010 Winter Olympics, when she was the official flag bearer and won a bronze in speed skating, she was frequently mobbed on the streets. As she writes in her book, “I had never before had the level of recognition I received in Vancouver, and I never want to have it again.”

What does interest her is the opportunity to use her platform to tell her true story and help debunk the myth that external success brings happiness.

After many years in the spotlight, she was frustrated by the linear approach to media interviews, which were either edited to tell the story the outlet wanted or were far too short to properly carry her message. “There’s not much you can say in four minutes,” she says. “I don’t think people really knew me at all.”

That matters to her. Clara, who seems set on finding clarity, cares that people know the truth: Behind the hype and the medals is a real person.

“I just wanted to expose more of myself and my story and let people know the places and spaces in between,” she says. “The experiences they’ve seen me have and the way they thought they knew me, it just all seemed so good and so easy… I wanted to be completely open about myself.”

That doesn’t mean it’s been painless for her to reveal so much.

She’s quick to point out “the really beautiful side of it.” The book signings have been “sharing experiences” in which people come up and tell her their own stories. But on a personal level, she says, “it’s been really traumatic. I’ve had to kind of go back into places I don’t really want to go, including with my dad and my early years in bike racing—they were really hard.”

To deal with it, she has been working with her psychologist and, more recently, with her naturopath to manage the anxiety, which she says is the most intense she’s ever experienced. She has dreams in which her father, who passed away in 2013, comes back and tells her he isn’t the way she describes him in her book.

“I could never have done this book if my dad were alive,” says Clara. “It’s really hard but I also know that so many people go through this exact thing, and it’s very important and it’s a big part of me. I’ll struggle with being a child of an alcoholic household for the rest of my life… This is really heavy for me and it’s really not fun, to be quite honest, but it is what it is.”

In the wind tunnel testing aerodynamics for 2012 Olympic time trial

“Follow your bliss and don’t be afraid…”

As punishing as that sounds, it comes as no surprise to anyone who knows Clara that she’d be up for the challenge. A big part of her philosophy, not to mention her success, has been to push through her doubts and struggles, to force herself to face them and then, as she writes, “empower yourself by conquering them.”

Even in her life today, which she happily shares with her husband of 16 years, she looks for things that they “love and care about and that teach us and fill us with absolute joy—things that are usually grueling and hard and take great endurance and suffering.”

She’s referring to things like epic cycling trips and her Appalachian Trail hike—the more constructive kind of suffering. But it is suffering, nonetheless.

“(Peter and I) take great satisfaction in the toil and in the struggle, and we value its role in bringing us to a place of bliss,” she says. “We kind of live in the way Joseph Campbell would write, the mythological historian, about following your bliss…. What will make us feel totally connected as human beings? Those are the things we seek out and they matter a lot to us.”

Suffering for a reason, to know yourself better, to improve and let others learn from your improvements; it’s an uncommon relationship with suffering, certainly in our culture. But Clara understands not only what it is to struggle but also that good can come of it.

Open Heart, Open Mind is dedicated “to anyone who has struggled or is struggling.” For Clara, it was important that her book, although a memoir, not truly be about her. “What I’m really saying is, ‘Please find yourself in this story and realize you’re not alone.’ I’ve been reminded by so many people that I’m not alone in the struggles I’ve had, and I think that matters. As human beings it matters to know you’re not alone in this.”

“Clara is one of the most unique people you will ever meet—she is unique in her ability to suffer physical pain and push through that suffering to achieve amazing athletic feats; she is unique in her ability to inspire others to work harder and elevate their aspirations to be better; and, perhaps most importantly, she is unique in her ability to connect with other people on a very human level to share her experience with depression in a way that is very positive and constructive. She is incredibly driven and seems to have an insatiable appetite for both humanitarian work and personal adventure. I don’t know anyone else like her and I’m so thankful I had the chance to train with her for eight years!” —Kristina Groves, Kickass Canadian, four-time Olympic medallist (speed skating)

“The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons…”

Offering readers hope and solidarity isn’t the only gift Clara bestows with her book. She’s donating her proceeds to charity. So far, Right to Play, Take a Hike, L’École Nationale d’Apprentissage par la Marionnette and the Canadian Mental Health Association have benefitted from her very open heart.

“It makes me feel good that I’m not standing there peddling something,” she says. “We’re all giving through this book… The more the book sells, the more money I’m able to give, so I’m really happy about that.”

This generosity is nothing new for Clara, who offers her time, money and energy to a long list of organizations. Most notably, she’s been an athlete ambassador for Right to Play since 2006. That relationship began when she won gold in the women’s 5000m skate at the Torino 2006 Winter Olympic Games and made use of the spotlight to announce that she would donate $10,000 of her personal savings to the charity. The experience taught her once and for all that medals only mean something to her if they represent more than just having crossed the finish line first.

She has also been the face of Bell Let’s Talk since 2010—the same year she received a star on Canada’s Walk of Fame, was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and had the Order of Canada she received in 2007 upgraded to Officer, but that’s not where her focus is.

By collaborating with Bell, Clara has been able to lend her voice to help break the silence and stigma surrounding mental illness. In 2014, she rode 11,000km across Canada for Clara’s Big Ride in support of the initiative. And every year, she champions Bell Let’s Talk day. The campaign has received criticism for corporatizing mental health issues—arguments Clara says she understands. But she still sees great value in attaching herself to the cause.

“I think of the people who talk to me on pretty much a daily basis and I think, ‘Should I not do this?’” she says. “And then not be there to help this person who’s just told me that I really helped them? Should I not go to the Olympics and compete because people have a hate on for the Olympics? I don’t think that’s an answer.

“As an individual I feel like I have an opportunity that I really need to take because it matters to me. I also see directly where (the) $80 million dollars (raised by Bell Let’s Talk) has gone. Knowing that Take a Hike in Vancouver was able to hire another social worker this year because of a community grant from Let’s Talk resonates with me… I’ve given $45,000 to organizations through my book so far and as I get money from book sales I’ll continue giving. But I don’t have $80 million dollars. And I’m not a person who has the capacity to do advertising or put myself out there and be there in the way that I can with Bell Let’s Talk. So that’s why I continue: Because it’s a great opportunity.”

“Clara is an inspiration to all Canadians. Women, men, children, athletes, leaders, citizens. She has taken on mental health in this country with courage and grace and her work is making a difference. We are all grateful to Clara for her tireless efforts to improve the lives of so many Canadians living with a mental illness today and in the future.” —Alyson Walker, Kickass Canadian, Vice-President, Brand Partnerships, Bell Media

From left: Right to Play founder Johann Koss, Kickass Canadian and Right to Play ambassador Martin Parnell, Clara

“To go through dark and devious ways before we can find the river of peace…”

By any measure, Clara continues to achieve great things. But they are things that matter to her personally; her journey is no longer about winning or escaping.

Life in Canmore, Alberta, where she and Peter have settled after years of “living all over,” is full of modesty and gratitude. Many of her current goals, as described in her book, “are small and invisible to others.” For example, changing her inner voice to a positive one that no longer channels her father; learning more about nature; being still, mindful and present; and, perhaps most of all, serving others.

She has a variety of jobs and projects lined up, including broadcast work for CBC during the Rio 2016 Summer Olympic Games. And she’ll be defending Lawrence Hill’s book The Illegal for Canada Reads 2016 from March 21 to 24.

For now, though, she’s focused on taking each day as it comes and making sure she stays grounded. “I just hope people realize that even when you’ve done all these big things, it doesn’t mean you wake up every day thinking, ‘I love life! I’m going to go run a four-minute mile!’” she says. “Some days I can hardly even go for a walk, I’m so unmotivated. But the gift is always the experience and I just try to live each day with a little nugget that’s going to be a positive one.

“I guess I’m trying to say that I’m just a very ordinary, flawed human being who does the best she can. I’m not pretending to be anything that I’m not; I’m just trying to take opportunities, if they’re good ones, to have a good impact and it’s nothing more than that. It’s not about creating a pedestal to stand on, it’s just really trying to connect at a human level as much as I can.”

A stop on her cycling honeymoon along the Dempster Highway, 2002

In case you were wondering, back on the Appalachian Trail, Clara did finish what she started; she did climb to the top of Mount Katahdin on that early morning in July 2015. But she did it on her terms, because she wanted to.

“On the second last day (of my hike), I was in Baxter State Park about five miles from the top of Mount Katahdin,” she says. “I was going to hike up it the next day, and everyone (I had met along the trail) was going into town to stay at a hostel and have a celebratory dinner before hiking Katahdin… I stayed in the park and I ended up having the hiker campground to myself, which is unheard of. And I had this amazing experience of being alone and being okay being alone.

“That was the most profound thing for me because I realized, ‘I know who I am. I don’t need to go into town and have that experience; my experience has actually been hiking up to 12 hours a day by myself.’ It taught me about myself and I’ve learned to be okay with being completely alone and being able to sit with myself without any distractions.

“So I had that camp to myself and then I woke up the next day as I always did at 4:30am, had some breakfast, packed up and hiked up to the top… I had just finished the Appalachian Trail and it really wasn’t a big deal. That whole Mount Katahdin part at the end of it just didn’t matter to me; I’m grateful I went up, but it wouldn’t have mattered if I hadn’t.”

* * *

For the latest on Clara, visit clara-hughes.com, ‘Like’ her Facebook page and follow @clarahughes on Twitter.

To read more about her story and join Clara in giving, you can order Open Heart, Open Mind.

Thank you to Simon & Schuster’s Amy Prentice for making this interview possible.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Thank you, Amanda, for another introduction to an inspiring and moving life in progress! Clara’s openness and honesty and heart and accomplishments are a tribute to the courage and kindness of the human spirit.

My pleasure, Catherine! It was a privilege to talk with Clara and hear some of her story. I’m so glad she’s sharing it. Thanks for reading!