Martin Parnell, quest seeker-sport lover-motivational speaker-Right To Play advocate

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: October 31, 2014

“What I've learned is that the capability for sport to educate and empower is universal.”

Did you know that play has the power to break down social barriers and promote collaboration? That learning through play can decrease the spread of disease by improving awareness? Or that play can inspire children to believe they can make a change and make a difference? Did you know that underprivileged children around the world, living in countries affected by war, poverty and disease, benefit significantly from play-based educational programs?

Did you know that Martin Parnell ran the distance of 250 marathons in 2010? Or that in 2011 he set the Guinness World Record for the longest netball game ever played, and in 2013 he climbed to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro in 21 hours, just three days after running the Kilimanjaro Marathon?

Amazing feats of athleticism and record-breaking achievements tend to get our attention. And why not? They take commitment, determination, talent and the ability to push through pain, and they often require years of dedication. But there are other things that deserve our attention even more, things that might not stand out so readily or be as easy to acknowledge. For example, poverty, conflict and disease, all of which affect underprivileged youth around the world—and all of which can be vastly improved by the seemingly simple act of play.

That’s what Martin wants us to know. His impressive accomplishments are all part of a five-year initiative called Quests for Kids, which he launched to raise funds and awareness for Right To Play, an incredible organization with a mission to educate and empower disadvantaged children through sport and play. He completes amazing physical endeavours to catch our attention, and then redirects it where it needs to be.

At the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, Africa, March 2013

In the words of Ottawa, Ontario’s Wing-Leung Chan, who nominated Martin as a Kickass Canadian, Martin is “using superhuman achievements to support those who are often overlooked.”

Martin’s first official quest started January 1, 2010, when he began a full year of completing 250 marathon-distance runs (42.2km). But the root of all this extends much further back, to a time when he was just a young boy growing up in Buckfastleigh, Devonshire, a rural farming area in England, with parents who always encouraged him and his five younger siblings to play sports, regardless of their skill level.

Completing the Sinister 7 Ultra, Crowsnest Pass, B.C., July 2009

The rules of the game

From the start, John and Mary Parnell believed that children should play sports simply for the love of the game and the benefits of physical activity. That was a tremendous gift to a child like Martin, who now says he was anything but athletically gifted in his youth.

“As a kid, I was what you call huggable,” he says. “I was big. In sport at school I was usually picked last. But my mum and dad encouraged us to play, and not just one sport, but everything.”

Martin and his siblings played soccer until dark, lost themselves in games of tennis and badminton, ran off to the cricket pitch as often as they could. By his teens, he had grown into his body, shedding his “baby fat” thanks to a growth spurt and a solid foundation of physical activity.

He doesn’t put much stock in his heftier beginnings, saying “I think it’s just the way it works out sometimes; some kids are bigger when they’re younger.” But the memories of being the kid who always gets left out during gym class stayed with him. “It can be a tough go for kids who aren’t super skillful from the age of four,” he says. “It certainly left an impression on me.” That impression reinforced the notion that sport is essential for all youngsters, and that playing, in and of itself, is the reward.

Running with students from West Dover Elementary School during Marathon Quest 250, Calgary, Alta., 2010

Due North

Martin made his way through grammar school happily participating in pick-up games for a whole whack of sports. When he graduated in 1974, he headed to the Camborne School of Mines at the University of Exeter in Cornwall, England, to pursue a mining engineering degree and, ultimately, a job that would enable him to travel the world. He’d read about the Canadian Rockies and Prairies, and had a yearning to visit our northern country, so he spent the summer after his second year at Camborne working for Cominco (now Teck) in Pine Point, Northwest Territories. For him, that sealed the deal; he knew Canada was the country for him.

After completing his degree in 1977, he returned to Canada to work for Cominco, this time at the Sullivan Mine in Kimberley, British Columbia. Two years later, he took a job in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, where he eventually picked up two wonderful things: Canadian citizenship and Wendy Neate, who soon became his first wife.

Martin and Wendy wound up in Sudbury, Ontario, where they adopted Kyle (then four) and Christina (then two), a local brother-and-sister pair in need of a home. The family spent nearly two wonderful decades together in Sudbury until Wendy lost her life to liver cancer in December 2001 at age 46.

Suddenly a widower with two grown children, Martin decided to make some changes. He left his job at Falconbridge Ltd. and moved to Cochrane, Alberta, where he started up an engineering consulting business, and where he still lives now. He also decided to start making more time for the things he really wanted to do.

Bungee jumping off Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River, Zambia, Africa, April 2005

Tour d’Afrique

Since moving to Canada, sport had continued to play a large role in Martin’s life, but it was always at an ad hoc, informal level. That changed in December 2002, when Martin agreed to run the 2003 Calgary Marathon with his brothers—a pivotal decision Martin calls “the biggest ‘Yes’ I’ve ever said.” He spent seven months introducing his body to the sport of running, and then, at age 48, completed the race in 3:54, even after taking a nasty fall and banging up his knees just 2km in.

His forays into endurance sports, including more marathons and triathlons, led to another pivotal event: In 2005, he fulfilled a lifelong dream of travelling to Africa. He joined the Tour d’Afrique as a leisure rider, spending four months cycling amidst racers and recreational cyclists all the way from Cairo, Egypt to Cape Town, South Africa. Martin says he “wasn’t a particularly good cyclist,” but, true to form, he didn’t let that stop him from embarking on a challenge and pursuing something he loved.

Tour d’Afrique, 2005

The Tour kicked off at the Great Pyramid of Giza on January 15, 2005. After two weeks of cycling through Egypt, the group crossed Lake Nasser and arrived at the Sudanese port of Wadi Haffi. At the end of the first day in Sudan, as the group was putting up their tents, something in the distance caught Martin’s attention: a makeshift soccer pitch, with handmade goals propped up in the sand. Never mind that he’d just spent all day cycling across Africa; Martin the soccer fanatic raced over and joined the local children in a two-hour pick-up game, happily passing the ball back and forth until sundown. “We had a great game of soccer and didn’t say a word,” he says. “We just laughed and cheered and played.”

Tour d’Afrique, 2005

The next morning, he packed up his tent, climbed back on his bike and carried on with the Tour, pedalling through Sudan and into Ethiopia. One morning while cycling through a southern village near Moyale, he saw two boys playing table tennis, another childhood love of Martin’s. He jumped off his bike and approached the players, wordlessly signalling for the bat. One of the youngsters graciously obliged, and Martin started up a game with the other.

“Within five minutes there were 100 kids around the table, yelling and screaming and cheering,” says Martin. “I must have looked a sight in my crash helmet and bike gear, they must have thought aliens had landed. But it was an amazing game and not a word was spoken, and that really was a turning point; I just felt the power of play and sport, particularly with kids, and realized that it didn’t matter how old you were, what language you spoke, what religion you practiced, what your culture or gender were—sport crosses all those boundaries.”

Throughout the rest of the Tour d’Afrique, these kinds of encounters kept happening to him. Everywhere he went, he found opportunities to run and play soccer and table tennis with African children. It quickly became the highlight of his trip. “When people ask me what I loved about Africa and what it was like to see Victoria Falls, (I tell them that) what I really enjoyed was the kids,” he says.

Right To Play

When Martin returned to Canada in May 2005, he was invigorated by his experience in Africa and inspired by his “awakening to the power of sport.” He just didn’t yet know what to do with it.

He continued pursuing other endurance sports, including his first Ironman triathlon in August 2005 in Penticton, British Columbia. (He also scored another victory that year, marrying Sue Carpenter-Parnell, who he calls his “greatest supporter.”) But it wasn’t until February 2009 that he realized where he ultimately wanted to channel his energies.

Tom Healy, an old friend of Martin’s from his Kimberley days, was in Calgary, Alberta and invited Martin to join him for dinner. Tom was involved with Right To Play and he spent the evening telling Martin what the organization was all about.

“I heard that night about how they use play-based programs to teach kids key life skills, leadership, team building and conflict resolution, (and that this) helps with prevention of diseases like HIV and malaria,” says Martin. “It struck a chord with me, particularly because of the Africa trip. Ever since the Tour d’Afrique, I knew I wanted to do something (to give back), but I didn’t have a vehicle to do something. Suddenly I hear about this organization that was using play in a way I could totally understand. Things started to click, it was like a piece of the jigsaw puzzle starting to come together, and I thought, ‘Here’s a group I’d like to get involved with.’”

It only takes $50 to give one child a Right To Play program for a full year. So he decided to start by helping 200 kids gain access to a program. He and Tom gathered several friends, and together they competed in marathons, triathlons and duathlons, raising $10,000 for Right To Play. Then, while preparing for a 100-miler later in 2009, for which he regularly logged 40+km training runs, Martin had an even bigger idea: he would run the distance of 365 marathons in one year, a total of 42.2km every day.

After speaking to his doctor, the number was pared down to 250, allowing for recovery days. But Martin’s commitment wasn’t pared back at all. Tracked online by GPS, and followed by fans on social media sites, he completed 10,550km between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010. One of those 250 runs included competing in the Queen City Marathon in Regina, Saskatchewan, for which Sue joined him, running her first marathon at age 58.

Running the Queen City Marathon with Sue at his side, Regina, Sask., September 2010

Martin raised $320,000, eclipsing his goal of $250,000 and giving 6,400 children the right to play. Little did he know, his marathon quest was to be the first of many.

The many shoes Martin used while running Marathon Quest 250

A fulfilling quest

In June 2011, Martin travelled to Benin, West Africa to visit five schools as an Honorary Athlete Ambassador for Right To Play. He was blown away by the phenomenal job the organization did, engaging and empowering youth by offering them what he says all kids want: “structure, some helping hands and some mentorship.”

Visiting an elementary school in Benin, Africa, June 2011

During the long flight back to Alberta, he settled on another idea: he would count Marathon Quest 250 as a starting point, with the goal of completing 10 quests in five years and raising $1 million for Right To Play—and 20,000 children. He would call it Quests for Kids.

So far, he has completed eight quests, incorporating running, netball, lacrosse, soccer, hockey and cycling to raise $577,000. (In fact, it’s more like $1,252,000, including matching funds from Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (CIDA) for donations contributed between April 2012 and October 2013, but Martin is only counting the direct donations in meeting his goal—although he’s overjoyed at the benefits children have received thanks to CIDA’s involvement.)

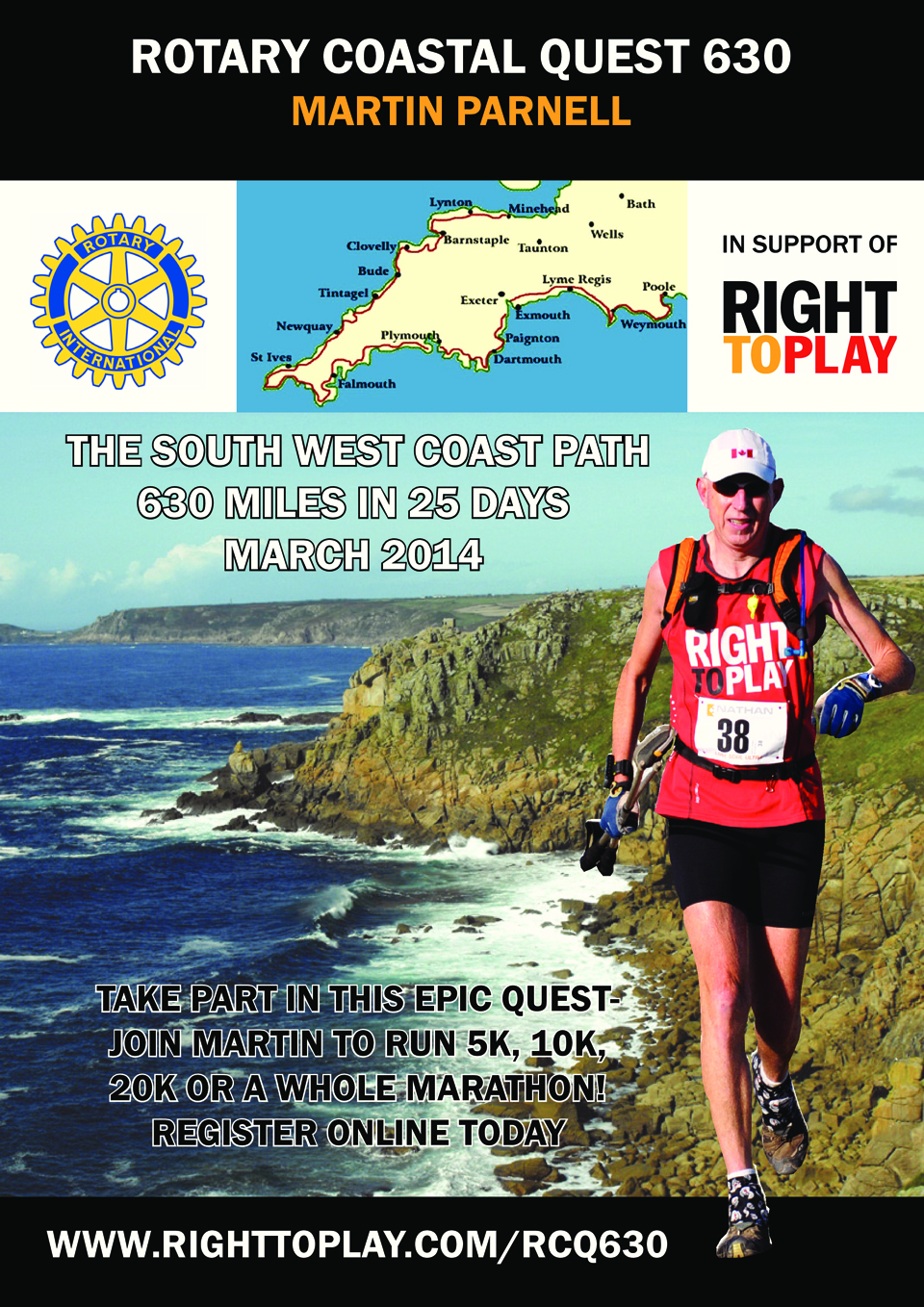

Next up is the Rotary Coastal Quest 630, which involves running the 1,000+km cliff pathway along Southwest England over a period of 25 days, beginning March 4, 2014. As for the 10th and final quest, he’s still looking for inspiration; right now, all he knows is that it will take place in autumn 2014, and that it will be something very special indeed.

Look after yourself, look after each other

Looking beyond 2014, Martin intends to expand on his career as an author (his first book, Marathon Quest, was published in 2012 by Rocky Mountain Books) and international keynote speaker. But one thing will remain the same: his steadfast commitment to Right To Play. He continues to donate 10% of the proceeds from his book and speaking engagements to the organization, and is passionate about helping them evolve even further in the coming years.

As it stands, Right To Play offers tailored programs in more than 20 countries affected by war, poverty and disease in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and North America. Since 2010, the organization has been on the ground in Canada’s First Nation communities, offering the Promoting Life-skills in Aboriginal Youth (PLAY) program with the goals of strengthening Aboriginal youth and their communities, and supporting the value of culture and identity. They currently work with more than 45 First Nation communities in northern Ontario, and, as of earlier this year, four First Nation communities in Manitoba.

In addition, Right To Play makes downloadable programs available for schools worldwide, with 5,000 Canadian schools currently participating.

Visiting children at Prairie Waters Elementary School during Marathon Quest 250, Chestermere, Alta., 2010

Martin sees Right To Play’s ability to engage youth from a variety of backgrounds and nationalities as a great sign of the organization’s success, not to mention its importance. “What I’ve learned is that the capability for sport to educate and empower is universal,” he says. “Obviously there are different issues in Africa compared with in Canada. When it comes to health issues, in Africa, it’s malaria, it’s HIV. But when you look at health issues in North America, Right To Play is dealing with diabetes and obesity. These are huge issues with our kids. And on a more general level, leadership skills and teamwork development are the same across the board. So those are the kinds of skills we can teach, and they’re universal, they’re not just something for disadvantaged kids; they can benefit everyone.

“Right To Play’s motto is ‘Look after yourself, look after one another.’” If kids can learn that message early on, it’ll be with them the rest of their lives.”

At the end of the TransRockies Quest 888, 2013

That motto is at the heart of what Martin promotes as a speaker. His “two-barreled message,” as he calls it, encourages people to follow their passions and not be afraid of “giving it a go,” and also to do whatever they can for those in need. He appreciates the fact that people are inspired by his quests and adventures, but what thrills him most of all is when people take his message on board and really commit to giving back to others.

This is what Martin does: capture our attention, and then redirect it where it’s needed most.

* * *

For the latest on Martin, visit martinparnell.com, follow @mp250 on Twitter, ‘Like’ his Facebook page or join him on LinkedIn. You can also email [email protected].

To support Martin’s fundraising efforts, visit Quests for Kids.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Martin

Proud to have you and Sue as friends. Your efforts have inspired us all and have touched the lives of many. Keep it up old buddy.

Tom

Thanks Tom,

Without you none of this would have happened. Love to Ulrica. Take care,

Martin

This is so cool!! Great to have you in the family. Stay well. Lyds xx

A great way to end the year, Amanda, with another heroic example of an inspiring Canadian, making a difference in the lives of young people, where it all begins!

Thanks, Catherine – so glad you enjoyed Martin’s story! Happy holidays to you. 🙂

Martin has been a huge inspiration for me, from the moment I first heard him interviewed on CBC several years ago (prior to his Marathon Quest 250) to every time I bump into him. He is full of life, such a giving, kind person and a true ambassador of the Canadian spirit. It’s very fitting that he has been honoured as the latest Kickass Canadian.

So great to hear, Blaine – you Kickass Canadians form a wonderful community, one I’m proud to support.

Thanks Blaine, loved your Aug. 30th article. You are definitely a “Kickass Canadian.” Cheers, Martin