Col. Chris Hadfield, astronaut-educator-explorer-musician-engineer-reality star

“We’ve had these squabbles over territory or history or religion, but meanwhile there’s an entire universe out there that puts it into perspective.”

Photo: NASA

The first time I saw Col. Chris Hadfield in person was at an Ottawa Folk Festival workshop this September. He was performing, and chatting, alongside his brother Dave Hadfield and MC Danny Michel. I knew, of course, that Chris is a brilliant and accomplished astronaut, pilot and engineer. But I was blown away by his philosophical intelligence, introspection and great wisdom.

Among other things in that far-too-short hour at the Folk Festival, he talked about our similarities as human beings. He said that when astronauts first go to space, they tend to look down to identify their hometowns, their countries. But then, quickly, as they orbit the planet, they realize how little difference there is from one place to the next; that borders disappear, and that we all, even with our individual circumstances and barriers, are trying to solve problems the same way. We’re scattered across the planet, but connected by biology, sociology and history.

On top of Chris’ insights, I was deeply impressed by how down to earth, gracious and humble he is. And that’s exactly the impression he gave me when, a few weeks after the Folk Festival, I interviewed him for this website. Friendly and personable from the start, he offered many wonderful reflections on life, told eloquently by a unique man who’s enjoyed an unparalleled vantage point (what he calls the “million-feet-away perspective”).

It’s my great honour to be able to share them here with you.

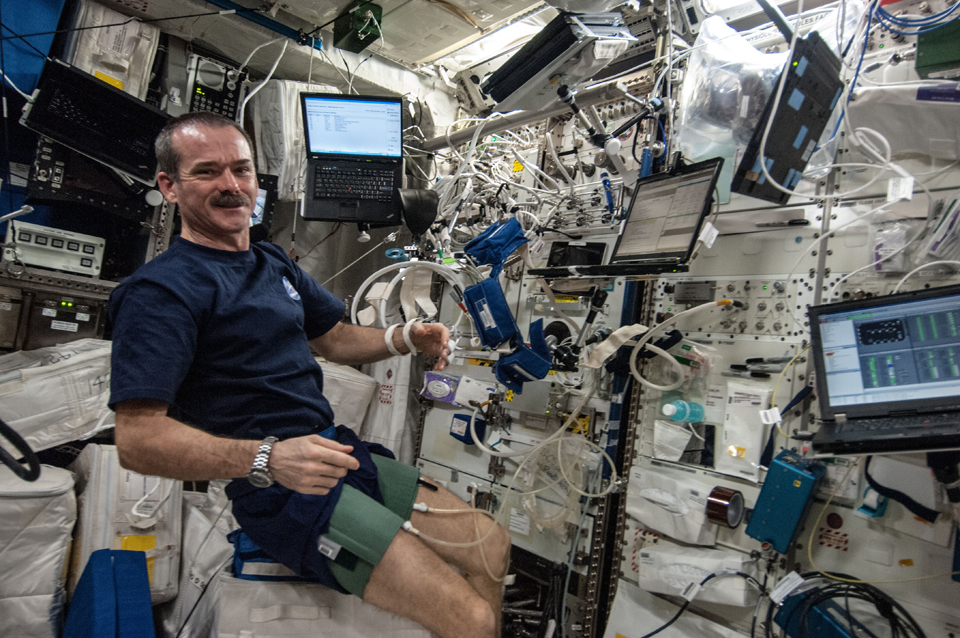

Performing experiments aboard the ISS, April 2013; Photo: NASA/CSA

A stellar path

But first, just who is this Col. Chris Hadfield?

He’s a Sarnia, Ontario-born dreamer turned mechanical engineer, turned test pilot, turned fighter pilot, turned astronaut, who then turned the world’s eyes to space during the five months he spent aboard the International Space Station (ISS) from December 2012 to May 2013. (“I got to watch the seasons of the world go entirely from one hemisphere to the other in the time I was up there,” he says. “It was amazing.”)

He captivated us with the greatest reality show of all—YouTube videos of his life in space, supported by heartfelt observations and incomparable photos via Twitter. His videos included educational clips, as well as music videos, like his duet with Barenaked Ladies lead singer Ed Robertson of their original song, Is Somebody Singing, and Chris’ cover of David Bowie’s Space Oddity (which received more than 10 million views in its first three days online).

Strumming his guitar aboard the ISS, December 2012; Photo: NASA

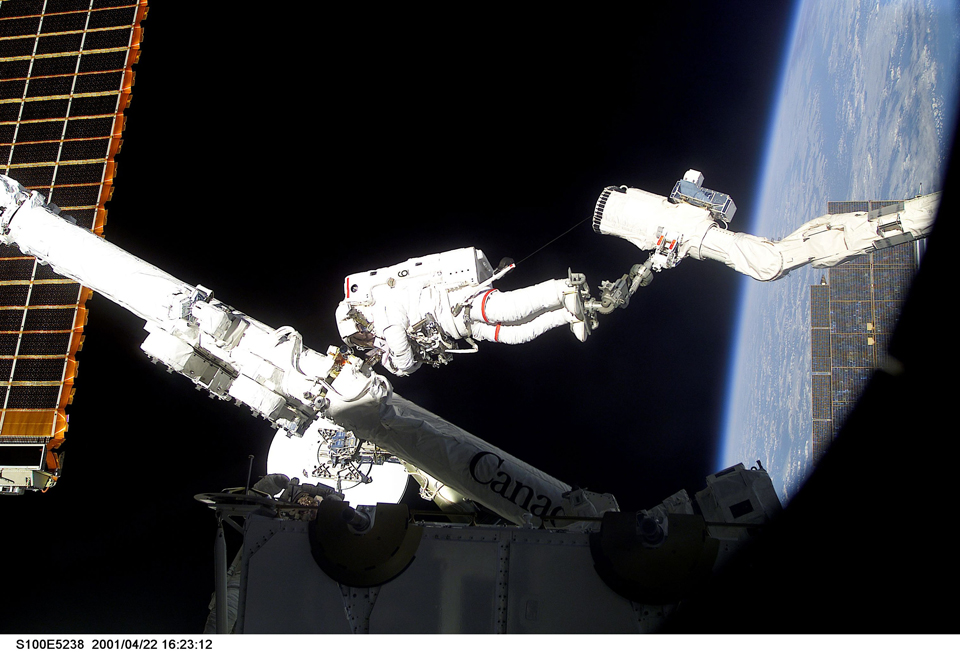

As Chris’ Canadian Space Agency (CSA) biography details, he truly is a first-rate Canadian. He was the first Canadian to operate the Canadarm in orbit (1995), the first Canadian to walk in space, as he helped install Canadarm 2 (2001), and the first Canadian to command the ISS (2013). He was also the first Canadian to hold both the military and civilian decorations of the Meritorious Service Cross (awarded in 2001 and 2013, respectively).

Other career highlights include:

- Becoming a member of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets and Canadian Armed Forces

- Graduating from the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC), with a Bachelor in Mechanical Engineering (1982)

- Conducting post-graduate research at the University of Waterloo (1982)

- Receiving a Master of Science in Aviation Systems at the University of Tennessee Space Institute (1992)

Launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis, with Chris aboard for his first trip to space, November 1995; Photo: NASA

Select honours and roles include being:

- Top graduate of the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School (1988)

- U.S. Navy test pilot of the year (1991)

- Selected by CSA as one of four new astronauts, from a field of 5330 applicants (1992)

- Capsule Communicator for 25 shuttle launches

- Director of NASA Operations in Star City, Russia (2001-2003)

- Chief of Robotics at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston (2003-2006)

Chris (right, second from front) and the STS-100 crew prepare to launch for an 11-day mission to the ISS, 2001; Photo: NASA

Chris Hadfield’s guide to life

I won’t delve too deeply into the details of Chris’ life—not because there aren’t enough fascinating facts to fill a book, but largely because there are; he has already collected them in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, his first book, which is published by Random House of Canada and is available to order at chrishadfield.ca. I had the privilege of reading an advance copy in preparation for our interview, and I wholeheartedly recommend it. The book is funny, engrossing, deeply informative, and also heartfelt and moving, bringing tears to my eyes more than once. It delivers healthy servings of each of: Chris’ personal story; his stellar career and three trips to space; and the practical life advice he gleaned from his extraordinary odyssey.

An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth takes us back to when a nine-year-old Canadian boy peered from behind a neighbour’s couch on July 20, 1969 to glimpse the television set that beamed out an image of Neil Armstrong walking on the Moon, and realized, in an instant, that he wanted to be an astronaut. That the impossible was possible, that he could overcome the odds and go to space, even when there was no Canadian space program. Even when Canadians weren’t leaving the planet. Even then.

In his book, Chris shares his childhood dreams. He also gets very real about his perceived failings in adulthood, including professional mistakes and the stumbles he took while trying to balance an obscenely demanding career with family—his “intimidatingly capable” wife Helene, whom he met in high school, and their children, Kyle, Evan (the mastermind behind Chris’ social media campaign) and Kristin.

Then, there are the thoroughly applicable insights Chris gained as an astronaut, and shares with us so we can live better on Earth. He offers tips like: have an attitude (one that keeps things in perspective and guides you in the right direction); embrace the power of negative thinking and sweat the small stuff (it helps you be better prepared); and aim to be a zero (so you don’t upset the balance).

He also recounts what it really feels like to launch and re-enter, aboard both a shuttle and a Soyuz rocket. How he felt on his first spacewalk, in 2001, and the unimaginable impact of seeing the universe and our planet from outside the spaceship. What it was like to oversee an emergency spacewalk just days before his scheduled return to Earth in May 2013.

An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth answers many questions. But it also brought up new ones for me. I thank my lucky stars that I had the opportunity to pose them directly to Chris.

Chris on a spacewalk to install Canadarm 2 on the ISS, with feet attached to Canadarm; Photo: NASA

The pride of Canada

In his book, Chris describes his return to space in December 2012 as “like coming home.” So I asked him where he now feels at home.

“I’ve lived more places than most people, if you just look at the globe itself. And of course I’ve lived off the planet for almost half a year, been around it about 2,500 times. You know when you go back to your parents’ house or you go back to the house of a sibling or a really good friend? There’s sort of almost a warm feeling to it, it has a return-to-a-previous-part-of-your-life feel to it that is really nice. Coming back to Earth had that feeling, just in general. I was feeling sick and it was a big tumult of everything, but at the same time, it had that feeling of returning to a beloved place. But on Earth, where I truly have that same feeling… is where I spent my formative years, and that’s southern Ontario.”

For that reason, Chris and Helene recently bought a house in Toronto and plan to make it their home base—ground control for the foreseeable future.

It’s hardly surprising that Chris chose Canada as his permanent residence. His book makes it very clear just how proud he is of his nationality. He mentions, among other things, that the lone guitar on the ISS is made by Vancouver, B.C.’s Jean Larrivée. And that when he, along with his fellow astronauts, was allowed to request people he’d like to talk to while aboard the ISS, his picks were Canadian musicians, including Bryan Adams and Sarah McLachlan.

So I asked him two questions along that theme. The first: What about being Canadian makes you most proud?

“How we treat each other. I’ve lived in (places that are organized differently), seen how other people have set up their type of civilization. Some of them are based on ancient, ancient cultures and prehistoric, tribal traditions that they don’t even think about anymore. Some follow a new set of rules, like if you live in the U.S.—that’s only a couple years old as a chosen way of setting up a society and living. And ours is fairly new as well, although it’s built on the older British-style system. But (because of) the way that it’s evolved in Canada… the longer I lived away from Canada, the more I felt Canadian. And that was really rooted in our fundamental expectation of how we treat each other and how we respect each other. It’s evident at the personal level, and you see it all the time in the government systems that we’ve set up, in the expectation that we have from each other and in government… It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s a world-leading solution as to how and why you should organize and set up a society, and it’s part of the reason I’m so lucky and proud to be from here.”

At the controls of Canadarm2, inside the Cupola of the ISS, February 2013; Photo: NASA

The second question: What about Canada’s space program makes you most proud?

“How well we have done for the amount of resources we’ve been given. You can measure it lots of different ways. Canada has had more people in space than any other country, except the monsters—except the United States and Russia, or the Soviet Union. We’re third. We were the third nation on Earth in space. And we have always found a specific part of it that makes sense for us, that brings out the best in us and makes the most money for us, and does us the most good—since the beginning, from the early telecommunication satellites, to the Canadarm, which has now gone on to its great-granddaughters of what we’re applying those robotics for. So I’m mostly just proud of how well we have done, how far above our weight we have fought.”

The Canadarm, performing the first robot-to-robot transfer in space, April 2001; Photo: NASA

A journey of discovery

One of the many things that stuck with me from Chris’ talk at the Folk Festival was his answer to a child’s question about whether there was life on other planets, in other galaxies. The gist of his reply was that, yes, odds are there is, and that we will eventually discover it.

In An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, he mentions a desire to constantly be “pushing the envelope of human knowledge and capability.” So I asked him what he thinks is the ultimate goal of space exploration—Finding alien life? Pursuing an endless quest to try to satisfy our curiosity?

“For me, the ultimate goal of space exploration is indistinguishable from the ultimate goal of all exploration, which is fundamental to human nature, and that is: an increasing understanding of self-awareness. ‘Where do we live? Where are we from? What is this for? Where did we come from? What does it mean for us? How can we do this better? How can we give more opportunity to our children and our grandchildren?’ That’s what exploration is about. That’s why kids leave home… Some kids 50,000 years ago walked out of Africa just out of a fundamental need for exploration, that sort of innate dissatisfaction with not knowing more.

“With space exploration, we’ve always taken the best of our technology, whether it’s how to dry and transport food so that we can travel a long way, or whether it’s a vehicle that carries us somewhere, or a way to navigate, or a combination of all three of those, we have always taken them as far as we can possibly go—to all the ends of the Earth, to Tasmania, to Antarctica. And now we are taking the best of our technology, just because we barely can, and we’re starting to actually leave the planet. It is just one long undeniable continuum, and I think it is both the reason for it and the purpose for it.”

Chris (front, centre) with the Expedition 35 crew in the Kibo laboratory aboard the ISS, April 2013; Photo: NASA

For someone like Chris, who craves knowledge and who’s seen the glory of the universe in a way that few people ever will, it’s hard not to wonder what he thinks about what made all of this possible to begin with. So I asked, Do you believe in a higher power?

“I fundamentally believe in the necessity to make the absolute most of yourself. To me, that is my guiding principle. I have enormous respect for everybody else’s belief systems. I am so disheartened and frustrated when people think that their belief system is so important that they are willing to do harm to other people in the name of it. I just find that unfathomably bad in human behaviour. To me, the most important thing is to have a belief system that gives you the strength to do the things that you’re capable of, so that you don’t despair, so that you don’t focus too much on the things that you can’t control or the fundamental unknowns. You need a fundamental belief system that gives your strength.

“I have nothing but respect for the ones that people have adopted for themselves and I really hope that people can respect each other’s belief systems enough that it (can serve to bring people together rather than push them apart). That’s the whole purpose of having (belief systems) at all, that’s why they exist within us. We talk about that onboard the spaceship, in fact, and when you get to see the whole world as one piece, I think it unites us all.”

He’s right. There are many reasons why religions form and people subscribe to them, but a particularly powerful one is the search for meaning, purpose and comfort—the need to believe there’s a point to our existence. In that way, Chris’ belief system fits beautifully; it offers something to strive for every day, and ensures that you’ll leave your best legacy behind. More than that, it’s a way of thinking that is inclusive and accepting, guiding us to goodness rather than destruction.

Chris (front right) and the Expedition 35 crew in the unity node aboard the ISS, April 2013; Photo: NASA

The next frontier

Another point that comes through in the book, repeatedly, is that Chris doesn’t see his retirement from CSA as an end, but rather as a beginning. Still, given that becoming an astronaut was his driving goal from age nine, I asked whether his focus or motivation hadn’t changed at least a bit since putting his days of space travel behind him. His beautiful answer?

“I didn’t put that part of my life behind me; I put it inside me… It’s an important part of the sequence of things that I’ve had a chance to experience… but I’m just as eager about the stuff that’s coming up as I have been about all the things that have happened so far. That same little nine-year-old boy is just as excited about what’s going on. It’s not like, ‘Okay, finally I got to fly in space, now everything else is just drudgery.’ It is the exact opposite of that. It’s like, ‘This is ALL delightful, AND I got to fly in space three times.’ So I’m really looking forward to everything else.”

Soyuz chutes deployed for landing, with Chris aboard, May 2013; Photo: NASA

Everything else includes accepting an appointment as adjunct professor at the University of Waterloo, where Chris plans to start teaching in aviation and other programs as of September 2014. It’s a natural transition, given that he studied there himself and has made a point of educating others throughout his career. He spent 20 years speaking about Canada’s space program, in tiny town halls, elementary schools and Rotary Clubs. In 2010, he started ‘On the Lunch Pad,’ a program through which he talked with students via Skype during his lunchtime. And while aboard the ISS this year, he led several Earth-to-ground connections with students across Canada, including a group at Chris Hadfield Public School in Milton, Ontario.

Plus, as Chris humbly says, “I think at this point in life, I have something to contribute.”

So education remains at the forefront. But there are other missions. “I sort of made up a list of things that are important and make me feel worthwhile, and teaching is one of those,” says Chris. “Feeling at the end of each day that I’ve done good things and worthwhile things is another. I put a lot of merit in technical competence and using it for good purposes, and so I’m on an advisory board to a couple different organizations and I would like to grow that in sort of a consulting and advisory role… I also want to be involved in music. So hopefully it’ll be a mix of all those things and we’ll see how this particular act of the play unfolds.”

Front, from left: Chris, cosmonaut Roman Romanenko and NASA astronaut Tom Marshburn, moments after being pulled from the Soyuz rocket, Kazakhstan, May 2013; Photo: NASA

On the music front, he recorded “an entire CD’s worth of original space music” while living aboard the ISS, and says that an album is in store at some point down the road. It’s one I personally can’t wait to hear; his passion and talent for music were clear when he played at the Folk Festival. (He had me at Canadian Tire.)

Still, as great as it was to hear Chris play live, amid a crowd of attentive listeners sharing in the experience, what I keep coming back to from that Saturday afternoon are his insights, the words he shared between songs. At one point, he told the audience that his time in space—watching over us all—made him feel even closer to his seven billion fellow earthlings, and that it left him even keener to get to know each person.

And so, weeks after the Folk Festival workshop, during our interview, I ask, Does science, like music, have the power to unite?

“I was a fighter pilot in the Cold War. I used to intercept Soviet bombers in Canadian airspace for a living, with an armed airplane that was intercepting armed Soviet bombers just off the coast of Canada, and when I became an astronaut, that was still the norm. And yet, because of the enemy of complexity and the challenge of trying to do something that basically supersedes transient grievances, we end up being unified… That’s where science can really play an important role. We’ve had these squabbles over territory or history or religion, but meanwhile there’s an entire universe out there that puts it into perspective. And if we’re going to try and go out and see what exists and see what it means to us, it is just too hard for one sub-tribe to do that; we have to go do that together.

“Within a few years of me being selected as an astronaut, I was on an international crew using an American space shuttle and a Canadian arm to build the Russian space station [Mir]. It’s a wonderful example of a higher motivation superseding more petty behaviours. And it is in the name of fundamental exploration and science that it happens. And I hope that that continues now. The Chinese have a really viable and focused and progressive space program, and it would just make sense, historically, if that same pattern that we followed in the early 90s with the Soviet Union/Russia could be followed with China, so that we could truly have an international space station, and when we go to the moon, an international outpost on the moon that is a representative of us all.

“It is not perfect and it is not simple, and it flies in the face of a lot of history and emotion, but the space station flies. I think it’s a wonderful example, and hopefully we can extend that example to include more people as we go further out.”

* * *

For the latest on Chris, and to order An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, visit chrishadfield.ca. You can also follow @Cmdr_Hadfield on Twitter, ‘Like’ his Facebook page and tune into his YouTube channel.

Thank you to Random House’s Scott Sellers for making this interview possible, and to CSA for making the photographs available.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Have just seen Gravity and have been contemplating the beauty and fragility of our Earth, forever turning. So uplifted to read of the thoughts of this extraordinary Canadian, Chris Hadfield, on the universe and humanity, and of his many and stellar accomplishments. Brava Amanda for highlighting this inspirational and so accomplished Canadian and humanitarian! Pride and perspective on what matters!

Thanks, Catherine! I’m ecstatic to have Chris on the site. 🙂

Chris is such an inspiration to me and so many other Canadians. He is truly a great example of what it means to be Canadian, and his perseverance and hard work definitely paid off! He is the only one in the WHOLE ENTIRE WORLD who can say “I’m the first Canadian to walk in space!” Truly an amazing guy, shows how far you can get in this world.

Thanks for the comment, Angie. Chris shows how far you can get even beyond this world. 🙂