Hannah Moscovitch, playwright-sensation

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: May 14, 2018

“I think about what it means to be a Canadian playwright in particular, and to want to write about Canada for Canadian audiences.”

Seeing the name ‘Hannah Moscovitch’ on a marquee was never the surprise. It was the ‘by’ that preceded her name.

I had always thought of Hannah as an actor. She hung with the drama crowd at Glebe Collegiate Institute (GCI), where we both went to high school, and we overlapped briefly at Trevor John Studios in Ottawa, Ontario, studying with acting teacher and Kickass Canadian Trevor John Leclerc. When I ran into Hannah a few years later during our post-secondary school days, she seemed excited about her acting classes at the National Theatre School (NTS) and the opportunity to play Nina in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull.

But things aren’t always what they seem. As I recently learned while interviewing Hannah for this website, she wasn’t quite as enthusiastic about her NTS studies as I’d thought. Not long after graduating in 2001, she shifted her focus entirely from acting to playwriting. And with that, a Canadian star exploded onto the theatre scene, lighting up marquees across North America.

Playing around

Since debuting her works Essay and The Russian Play at Toronto, Ontario’s SummerWorks Festival in 2005, Hannah’s been in constant demand. (It didn’t hurt that Essay won the Contra Guys Award for Best New Play and The Russian Play won the Jury Prize for Best New Production.) She’s gone on to write a slew of plays, all to great acclaim. In particular, Hannah won a 2009 Dora Mavor Moore Award for In This World, “an exploration of race, class and sex” (for young audiences), and was nominated for the 2009 Governor General’s Literary Award for East of Berlin, about a young man’s struggle to understand his Nazi father’s past crimes. East of Berlin was also a finalist for the 2010 Susan Smith Blackburn Prize.

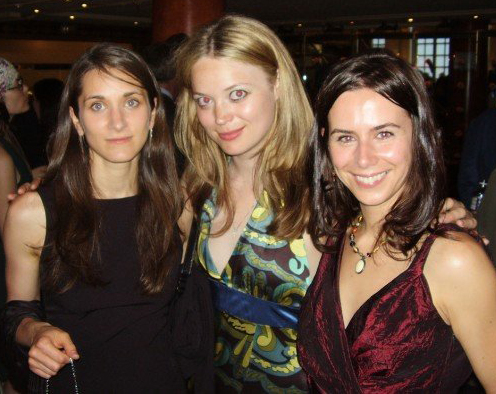

Hannah (far left) at the 2007 Dora Awards with ‘The Russian Play’ actor, and nominee, Michelle Monteith (centre) and the play’s director, Natasha Mytnowych, Toronto, Ont.

Hannah’s plays have been mounted across Canada and in several major American cities, including Chicago and Los Angeles. She’s written for CBC Radio’s hit program Afghanada, and has several works-in-progress commissioned by major theatre companies across North America, including The Banff Centre, Prairie Theatre Exchange (PTE), 2b theatre and New York’s Manhattan Theatre Club (MTC). She even has a couple film projects in development.

But that’s just the beginning. From late 2012 to early 2013, Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre—where Hannah is currently a playwright-in-residence—will feature a mini-festival of four of her plays: In This World, Little One, Other People’s Children and This is War. All but the first will be world premieres.

The plays are so fresh that she hasn’t even finished working on all of them yet. When I caught up with her for our interview, she was in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, revising This Is War and visiting her long-term partner, 2b theatre co-artistic director Christian Barry.

During “breaks” from her own playwriting, she’s making time to lend her expertise on a very special upcoming project with 2b theatre. Directed by Christian and starring Hawksley Workman, The God That Comes is “one-man live performance that fuses the chaotic revelry of a rock concert with the captivating intimacy of theatrical storytelling.” The piece, which is still in development, will have a one-time showing at SummerWorks this August before being workshopped for its 2013 premiere at Alberta Theatre Projects (ATP) in Calgary.

“I’m really excited about it right now,” says Hannah, who’s providing supplemental text for the largely musical piece. “Hawksley is such a great performer and I love his music. It’s the best vanity/distraction project for me.”

Setting the stage for success

What Hannah’s being “distracted” from is a very long list of works-in-progress that includes an extremely impressive clientele. For example, she’s been commissioned by the Stratford Shakespeare Festival to develop a play she describes as “Mad Men-esque.”

Stratford, she says, has been a longtime supporter of hers, and even offered her a summer residency in 2009. It stands to reason that a company with such a long and successful history would have keen instincts for spotting talent. But she is still humbled by their attention. “It was so, so nice to have been commissioned alongside people like Daniel MacIvor and George F. Walker and Judith Thompson, who are my theatre heroes.”

Other theatre heroes include Kickass Canadian Ann-Marie MacDonald, the brilliant playwright-actor-novelist behind the Giller-nominated book Fall On Your Knees. It just so happens that Hannah has been commissioned to adapt the novel for the stage by none other than the National Arts Centre (NAC). “It’s so intimidating that I’m numb,” she says. “I’ve gone through how awful-scary it is and now I’m just numb to it and I’m just working on it.” Hannah’s forging ahead alongside co-writer Alisa Palmer, and with MacDonald’s full blessing. “We always say that Ann-Marie is a guardian angel on the production,” says Hannah.

The play is a few years away from hitting the NAC stage, partly because “these things take so long to develop,” but also because of the book’s heavy emphasis on music. Right now, the adaptation is taking the form of a three-part, nine-hour long saga that may end up as an “extremely unconventional musical.”

If you’ve read Fall On Your Knees, it may seem odd to even consider adapting it as a musical. But Hannah has made a career of taking risks, challenging audiences and going the unconventional route. She prefers complex characters and isn’t afraid to write antagonistic protagonists—or, as she calls them, “beautiful assholes.”

Playful beginnings

This bold way of thinking was instilled from a young age. Hannah credits her parents, Allan Moscovitch and Julie White, with “encouraging me to develop my mind. They were very clear about the kind of brain they wanted (me and my sister to have): one that could go anywhere and think of anything.”

So, Hannah did. Near the end of high school, she’d auditioned for NTS at the encouragement of her high school drama teacher. When she wasn’t accepted, she spent a year abroad, first on a Kibbutz near the Golan Heights in Israel, then doing “crazy-boring temp work” in Uxbridge, England while exploring her British heritage.

Upon her return to Canada, she had a bone to pick. She auditioned again for NTS, not because she felt that acting was her calling, but because, as she says, “I was determined that no one turn me down for anything.” That motivation didn’t lay the best groundwork for a fertile learning environment. Hannah was accepted the second time around, but was, in her words, “a really shitty student. I just really didn’t understand anything they were saying to me… I was very hostile about the program itself, and that was reflected in how I behaved.”

In spite of her distaste for the acting program, and the fact that her instructors repeatedly tried to get her to leave, she stuck it out. “I was determined to finish the program, even though I was really out of my depth.” Still, she acknowledges that it was more than just youthful stubbornness and pride that kept her at the school. “There was something in me that knew I was an artist.”

A writer is born

That artist began to blossom when Hannah took a playwriting course as part of her NTS curriculum. She adored it, but still resisted her teachers’ attempts to have her switch from the acting stream to the playwriting stream. “I was very insulted,” she says. “I think it was very clear, to everyone except me, that I was a writer.”

Eventually, though, her vision got a little clearer. After finishing up at NTS, she moved to Toronto, where she waited tables and studied literature at the University of Toronto. She also spent many long hours bussing to and from Ottawa, where she acted with Salamander Theatre for Young Audiences and took part in the NAC/Great Canadian Theatre Company (GCTC) playwright’s unit. “I was doing a bunch of different things until I worked it out.”

What worked out was writing.

Hannah didn’t pull up her acting roots entirely; she says she draws on what she learned at NTS “to create characters that will support actors onstage so that they can perform and connect to the audience.” It’s just that she’s grown in a different direction, one that suits her and the theatre world very well.

Looking back on her evolution as a playwright, she says her work has progressed from being more about instinct and ego, to really focusing on craft and what it is she wants to say—what’s most important to her. “Christian and I were just talking about how, when you get older, you need faith or belief in the project that you’re working on. You’re not running on animal instincts like you were when you were younger… You have to have confidence in the project itself and that the content you’re talking about is beautiful and moving and intelligent and worthwhile. That’s what carries you.”

Hannah has also come to deeply value the collaborative aspect of playwriting, something she was introduced to at SummerWorks. “We put up plays ourselves at SummerWorks, which is great because it gives you control over the whole production. It made me a better playwright because I was involved in synthesizing all of the different elements of a show—text, design, direction, acting and even publicity… That was really defining for me in terms of inventing myself as a playwright, in that I realized that I want to work very closely with my collaborators.”

Writing her future

Whom she collaborates with is something that weighs heavily on Hannah’s mind these days. Her rise to acclaim has been fast, but it’s also been very steep. She’s already attracted attention south of the border, and not just from the theatre world.

Earlier this year, she met with an agent from Creative Artists Agency (CAA) in Los Angeles, who was interested in repping her for television writing. Many of the Canadian playwrights she’s known have already moved on to TV, and Hannah feels she may be approaching a crossroads in her career. “For me, there’s a big question about whether I want to be a Canadian playwright or an American TV writer.”

On the one hand, she’s most interested in working with great artists and is open to going wherever opportunity knocks. On the other hand, she feels a strong patriotism that keeps her very happy here in Canada.

“I don’t think I really thought about Canada much at the beginning of my career, when I just started writing plays. But because my plays have gone across Canada and I’ve travelled a bit with them, I have gotten more of a national perspective. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve thought more about what I’m trying to do (with my writing)… Now, I think about what it means to be a Canadian playwright in particular, and to want to write about Canada for Canadian audiences.”

As she continues to seek the answer to where her career, and her life, should go, she’s careful to choose her path for the right reasons. “I try to think more and more about being guided by my vision, being guided by what I desire rather than fear. I want to go towards things that I really want as opposed to running away from things I don’t want.”

That approach, much like Hannah’s name on the marquee, comes as no surprise. Just like her plays, the playwright has never backed down from revealing truths.

* * *

For the latest on Hannah, follow @moscotweets on Twitter and feel free to add her on Facebook.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians