Patrice Vermette, production designer

“When you create something, you don’t create it for yourself—you create it for people to appreciate.”

Photo by Chiabella James; all images courtesy of Patrice Vermette

To be a successful production designer requires more than vision, talent and artistry. It also takes passion, dedication and a desire to elevate others.

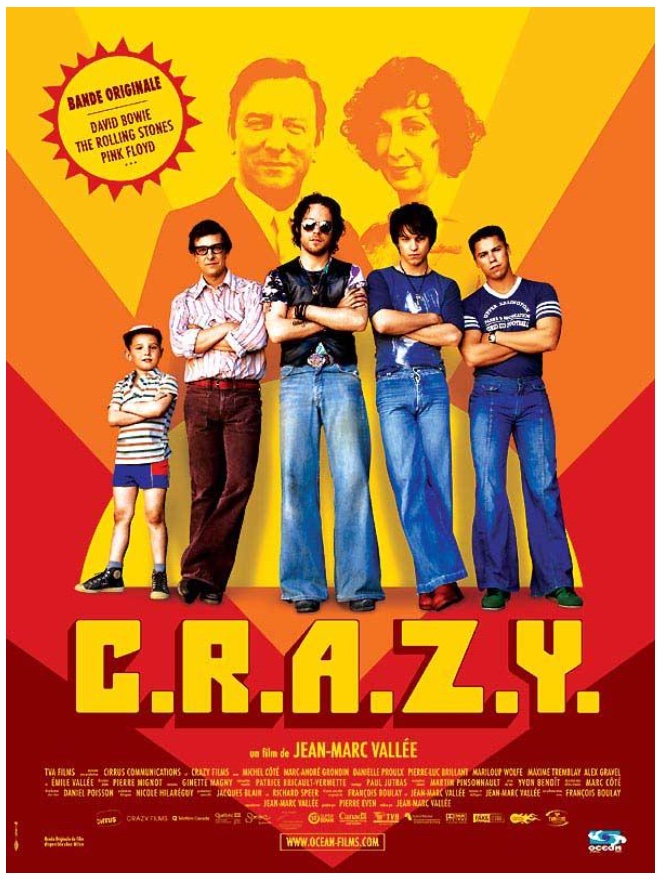

Patrice Vermette is a world-class production designer. His artistic gifts are on full display in the many films he’s worked on, and he has multiple awards and nominations to show for it, including a Genie Award (now Canadian Screen Award) for C.R.A.Z.Y., as well as nominations for 1981, Café de Flore and Enemy; and two Academy Award nominations, for The Young Victoria and Arrival.

But in talking with him and hearing from others, his human qualities shine through in abundance. He frequently praises his teammates and clearly sees filmmaking as a communal effort, not a hierarchy; he speaks with reverence about all the departments. I’ve interviewed him for a few articles, and from the first time we connected he’s been friendly, enthusiastic, gracious, supportive and incredibly generous. Twice he made time for a call with me while overseas and working seven-day weeks.

One of those times was for this interview. I reached him on a Sunday morning from his temporary office in Melbourne, Australia, where he’s worked since September. He’s been doing “full-on prep” for Foe, a sci-fi thriller based on the novel by Kingston, Ontario writer Iain Reid, directed by Garth Davis and starring Saoirse Ronan, Paul Mescal and Aaron Pierre. On evenings and weekends, he’s also been working on Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two, which he’ll be fully immersed in after returning home to Montreal, Quebec for a brief Christmas break.

His wife, painter Martine Bertrand, joined him for his first months in Australia. They’ve been a couple since meeting at a Halloween party in 1993, though ‘togetherness’ took on new meaning when they arrived in Sydney and spent 14 days quarantining in a hotel, per COVID protocol. “She made the trip out of pure love, to be locked in a room with me for two weeks,” says Patrice. “We were both working in that room, but basically, you’re in confinement. We had the room and we had a balcony and we could order in from Uber eats.”

Once they were in Melbourne and freer to roam, he was quick to discover a new favourite restaurant—his tradition when on location. “Melbourne is a foodie’s paradise, just like Montreal or Toronto,” he says. “There’s some really great spots.” For the Foe shoot, his top spot is a Spanish restaurant just minutes from his apartment, called Añada. “It’s funny, the first time my wife and I walked in, we saw the sign and we said, ‘We’re just missing the C; let’s go eat in Canada.’”

Those evening meals are just about the only time he breaks from working. It’s that commitment that helped establish him firmly in the film industry as one of the greats. He’s known for evocative, intricately detailed production designs that capture far more than style and history: they create a mood. “I think the best compliment I could get about my work is when the actors walk (on set) and they say, ‘Thank you, because it helps us understand who our characters are—it helps us do our job,’” he says.

For all his films, he follows a proven process, beginning by assembling a mood board of images and photographs, which capture the story’s essence and inspire the locations the crew will go on to find. “Production design is there to create the world that will put the audience in the right (emotional space). Whether you build a set, a house, whether you just find the right location—or sometimes it’s just a location and then it’s a plastic bag that floats in the wind… Whether it’s the colour on the wall or the right wallpaper, there’s a million choices you can make but it’s always there to support the story.”

“As an actor, we have the challenge of utilizing our imaginations to place ourselves into worlds and settings that are sometimes quite foreign from those that we’ve known. Whether that world was the hiding place for a terrified man who is trying to work through the trauma of his childhood (as in Prisoners), or the stark and austere halls of the Harkonnen fortress on Giedi Prime in Dune, I was instantly transported to another place both physically and emotionally when I stepped into the spaces crafted under the supreme talent of Patrice Vermette. His passion is felt throughout every inch of the set and it’s been a great gift to play in the spaces he’s created with Denis.” —David Dastmalchian, actor (The Dark Knight, Prisoners, Blade Runner 2049, The Suicide Squad, Dune)

David Dastmalchian as Bob Taylor in “Prisoners”

From “Prisoners”

Vermette family mood board

Patrice’s own story began with strong supports in place. Growing up in the Montreal suburb of Brossard, he was the youngest of three children, “raised by parents who were still together,” he says. It was “a loving family.” His father, Clermont Vermette, was a lawyer and his mother, Francine Bricault, had “the most important job in the world: she was making sure we were alright and we had enough love around us.” When Patrice was older, his mother took work managing an art gallery.

Both of his parents were “extremely open to the arts” and prioritized exposing their children to a range of influences and cultures. They frequented the Montreal Botanical Garden, museums and symphony orchestra concert halls, and “were privileged enough to be able to travel a lot.” The first movie Patrice remembers seeing, when he was four or five years old, was Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Flute—a Swedish film shot in black and white.

Perhaps the clearest defining moment in sparking Patrice’s inner production designer was when his father took him to the local cinema to see Star Wars. “Through my eyes—the eyes of a seven-year-old boy—I heard the music and I saw a whole new world opening up to me.” (Music remains a passion of his; he plays the piano, guitar and drums, and sees musicality in the way good production design “seduces audiences without their realizing it.”) Enthralled by the score, he stayed in his seat for the full end credits and was amazed to see the names of so many people. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, it takes a lot of people to make a movie.’ I think that was my first exposure to seeing that (and realizing), ‘Oh, those are the people who do that for a living!’ It’s quite extraordinary.”

“When I arrived at the New Mexico offices of Sicario, fresh from the airport, I walked into the art department and Patrice started showing me the ideas that he had for the film, through images displayed on the walls of our conference room. After about 15 minutes, I asked him if I could please put my bags down. Right then, I saw the passion that Patrice had for the work in front of him/us. We had dinner that evening and I met the social side of Patrice, who showed his passion for his family, for cooking, laughing, for enjoying life. These many years and a few wonderful projects later, my dear friend Patrice possesses that same passion for whatever is in front of him, for work or for his lovely family, whom I have gotten to know and love. In our industry, there are some visionaries who ‘see’ the film in their mind before they finish reading the script. Patrice is one of those rare artists who sees clearly how to tell and support the story, is in sync with the director (especially Denis Villeneuve), but is completely open and supportive of the ideas of the creative people he surrounds himself with. He, and Denis as well, are so respectful of collaborators’ ideas that help complete the storytelling, creative process that the energy while working with them is palpable. Patrice’s exuberance is contagious and awakens creative juices in the entire team. It is so much fun to be in his presence, even if there is only time for a quick beverage. For me, he brightens any day.” —Jan Pascale, set decorator (Sicario, Vice, Mank, Top Gun: Maverick)

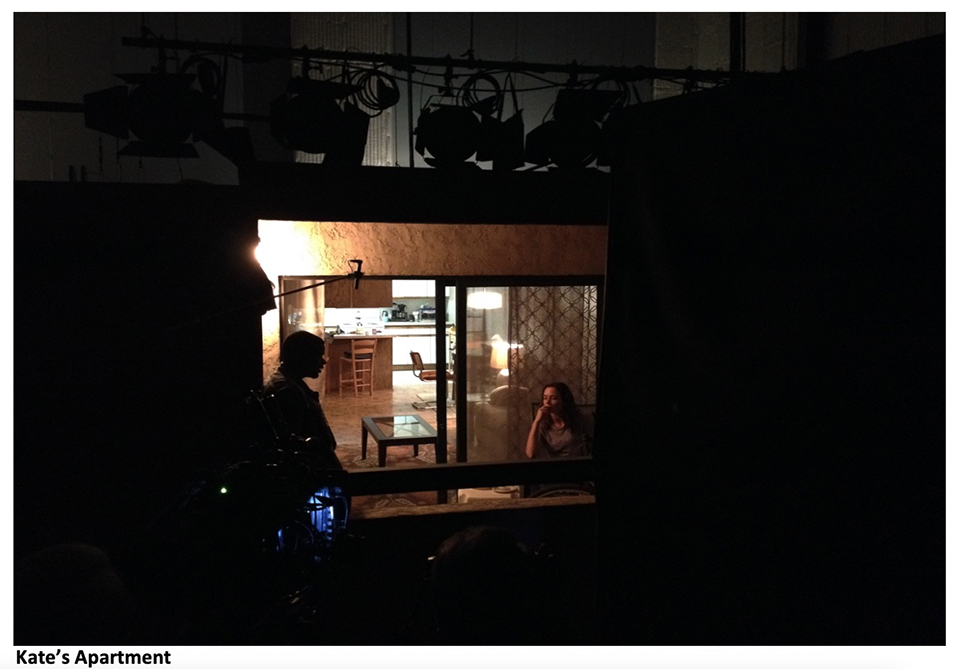

Emily Blunt as FBI agent Kate Macer in “Sicario”

From “Sicario”

Possible worlds

The end of that screening was the beginning of Patrice finding ways to transform the idea of other worlds into something tangible. His childhood home had an unfinished basement, and “that became my playground.” Lego pieces, Fisher Price toys, Star Wars figures—all were welcome in his underground studio. When his parents had guests over, they’d bring them downstairs to see what their youngest child had devised, and discover where their furniture, fabric and odd bits of cardboard had wound up.

“It was quite funny,” says Patrice. “What began in one little corner became two-thirds of the basement. It was a bit crazy for a while.”

It was bound to get crazier.

Patrice attended Collège de Montreal, a small then-all-boys high school (one of his classmates was future astronaut David Saint-Jacques). After completing CÉGEP at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf in 1989, he enrolled in communication studies at Concordia University, specializing in sound design. He earned high grades but wound up leaving two electives shy of a degree, in favour of working in the art department on music videos and television commercials. (His 20-year-old daughter, Lili, is currently in the same program he was in; she’ll graduate from Concordia in spring 2023, and, says Patrice, “one of my dreams is to graduate with her.”)

He likens his work on “small, indie” music videos to an apprenticeship, an extension of his schooling. “I learned by trial and error. You start analyzing and overanalyzing things and find other ways of doing things that (might be unorthodox).” The low-budget projects necessitated creativity. They also meant that he often worked unpaid. It wasn’t until he began art-directing commercials that a bit of money started coming in.

When he expanded his repertoire to include short films, he met someone who would become one of his first key collaborators: in 1996, he worked as a production designer for Les mots magiques, from director Jean-Marc Vallée (who went on to direct Dallas Buyers Club, Wild and Big Little Lies, among many other productions). The two filmmakers were fast friends and started collaborating on commercials. “We were just having fun, re-writing the agency scripts and coming up with our own approach,” says Patrice.

After countless commercials together, Jean-Marc asked Patrice to read a feature film script he’d written and consider working on it with him. Patrice wasn’t sure he wanted to stop his commercial work, but when he read the script, he was sold: it was for C.R.A.Z.Y., which later won Genie Awards in 2006 for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. “That’s the film that really gave us wings.”

From “C.R.A.Z.Y.”

From “C.R.A.Z.Y.”

But having felt the air up there, he was reluctant to abandon his commercial work unless it was for a film of the same caliber as C.R.A.Z.Y. That project eventually arrived in the form of The Young Victoria. “Jean-Marc said he had a film for us that was going to be shot in England, about Queen Victoria,” says Patrice. “He asked if I wanted in, and I said, ‘Sure, but wouldn’t you want someone with more experience to go to England?’ He said, ‘No, I want to work with you.’ So, I said, ‘Okay, let’s do it.’”

Still, Patrice was insecure about his ability to deliver on a film that detailed the history of, at that time, the longest reigning monarch in British history—particularly as a francophone. Ever a perfectionist, he took four months off from working on commercials to “just read and read and read and read about that period, and about Queen Victoria, so I had a good background fresh in my memory—background of historical facts and also the etiquette of the court back then.”

Princess Victoria and Duchess of Kent’s Kensington Palace bedroom, Shepperton Studios, 2007

Emily Blunt as Princess Victoria

Victoria Duchess of Kent’s drawing room, Shepperton Studios

Victoria William IV Birthday Banquet August 1936

Birthday banquet scene

The work paid off; Patrice received his first Academy Award nomination for The Young Victoria. (“By total surprise,” he says.) After that, films began flowing to him. He did production design for a third feature with Jean-Marc, Café de Flore, and travelled to Budapest to shoot a small Spanish movie, La banda Picasso, for director Fernando Colomo, where he met another of his key collaborators, “amazing art director” Tibor Lázár. And then “I came back (to Canada), and then Denis Villeneuve came along.”

“What else to say about Pat, we all know he kicks ass, ‘au sens figure,’ of course, pas ‘au sens propre,’ he’s too sweet and too much of a gentleman for that. He’s so gifted, talented, intelligent, sensitive, creative, he’s got such taste and he works so hard. No wonder everything he touches turns gold. L’essayer, c’est l’adopter.” —Jean-Marc Vallée, director (C.R.A.Z.Y., The Young Victoria, Dallas Buyers Club, Wild, Big Little Lies)

Vermette, Villeneuve and beyond

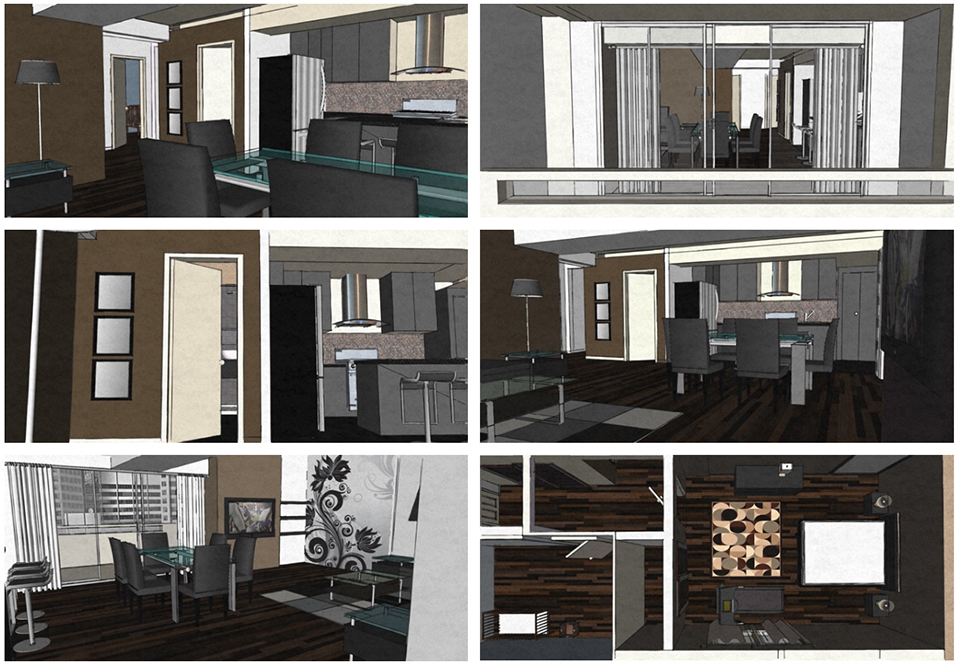

Patrice and Denis (also a Kickass Canadian) first worked together in the 1990s, when they did a few commercials together. But the timing hadn’t worked out for them to collaborate on a film. After the Budapest shoot, Patrice knew he didn’t want to go back to making commercials; he wanted to continue working on movies—good movies. And with that thought came an opportunity from Denis, in 2012: to shoot Enemy in Toronto, Ontario. Not only did it cement their partnership, it also introduced Patrice to storyboard artist and concept designer (and Kickass Canadian) Sam Hudecki, and graphic designer Aaron Morrison. “Those two became my friends and close collaborators since that year,” says Patrice, adding that Aaron has worked with him on every film since.

Concept art for “Enemy”

Finished set for “Enemy”

Patrice did production design for Denis’ next three projects: Prisoners, Sicario and the sci-fi Arrival. (Though he’s quick to point out that “Jean-Marc is still one of my best friends, I love that person. Jean-Marc is family.”)

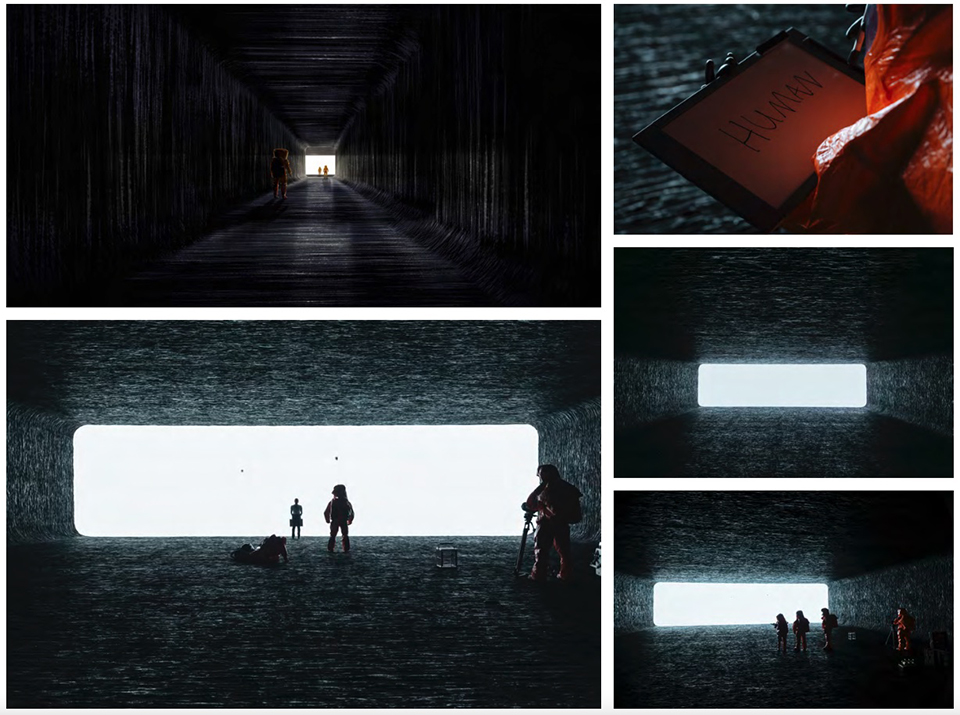

Arrival was an especially resonant film for Patrice. The year they shot it “was my dad’s last year on Earth, on this planet—wherever he is now.” The shoot was initially planned to be in Vancouver, B.C., “but the stars aligned for the movie to be transferred to Montreal, and it was quite important for me to be with my dad during that moment.”

His father passed away on October 7, 2015, after Arrival wrapped, but his father’s illness was something Patrice carried with him throughout production. That film, and in particular the interior design of the spacecraft, with its brilliant white light at the end of the tunnel leading toward the aliens, became even more meaningful for Patrice: the way the characters are lifted into the light, as well as the idea of life coming full circle.

“We included the circulatory concept in a lot of the sets—the hospital set, where we see birth and death; the office where Louise [played by Amy Adams] works, it’s a circular corridor; the house where she lives… All of that symbolism is there.” (It was “a family experience” in other ways, too: Martine designed the prototype for the aliens’ visual language, and their son, Arnaud, who is now 18, drew the ‘mom and dad saved the world’ picture that Louise’s daughter made.)

From “Arrival”

Amy Adams as Dr. Louise Banks in “Arrival”

After shooting Arrival, while Denis went on to make Blade Runner 2049, Patrice worked on a film that provided him with much-needed “comic relief”: Gringo, shot in Mexico with director Nash Edgerton. “It was perfect timing for me,” says Patrice. Then came The Mountain Between Us in Alberta and British Columbia, for director Hany Abu-Assad—who happens to be the artist behind two movies on Patrice’s Top 20 list: Paradise Now and Omar.

When Arrival was released, it brought about Patrice’s second Academy Award nomination. During that period, he was approached by writer-director Adam McKay, who wanted Patrice to design his next film, Vice. “We fell in love,” says Patrice. “It was a big bromance because I love politics and I think his writing is so intelligent and so to-the-point, and it makes you think about our world again.” Vice also connected him to cinematographer Greig Fraser, “now my unofficial brother.”

From “Vice”

When Denis approached Patrice about working on Dune—the epic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic sci-fi novel—they quickly agreed that Greig should join their team. (Patrice was also excited to be “reuniting with my friend Tibor again!”)

Like Denis, Patrice read Dune in his early teens, but for him it was because he was reading “every sci-fi book I could get my hands on. It was a book amongst other books. It did not become something visceral as it did for Denis.” (For the record, the books that shook Patrice’s core were 1984 by George Orwell and L’Étranger by Albert Camus. “They still haunt me, those books. I would love to work on adaptations of those.”)

Even so, Denis’ inspired take on Dune ignited the same passion Patrice brings to every project—and led the entire cast and crew to deliver an exquisitely realized work of art. The film was released in October of this year, and earned such critical and commercial success that its sequel was greenlit not long afterward. Filming on Dune: Part Two takes place from July to November 2022, in Budapest and Jordan, among other locations. It’s a monumental project for everyone involved. For Patrice, it’s also an opportunity to relish every detail, as he always does, and to draw on the immense expertise he’s acquired over three decades of design.

“I met Patrice Vermette on Enemy, where he introduced me to Denis Villeneuve and put in motion a relationship that has spanned a decade so far. I’ll always remember when I first walked onto the apartment set for Enemy; it felt unlike any constructed set I had visited before—this was a place imbued with a soul. I was fully transported. It was the first time I felt such a depth of detail that it seemed like this was more than a film set. It was a living character with its own history and texture so rich that I found myself captured by the smallest detail. Patrice is a filmmaker to the core. I feel so lucky to have met him because our conversations have opened my eyes to the deep investigation and possibilities of delving into what makes cinema. He is someone who puts his feeling and intellect so deeply into the composition of the environments in a film that they play musically together like they are part of the score itself. It’s difficult to summarize the spirit and energy that Pat brings to a production. I feel like the design he creates imbues not just the sets but the production itself. He makes every department feel like part of one family. At the same time there is no edge to the envelope of ideas he can push. It is no wonder that actors feel the presence of his sets and that cinematographers and directors find that they pick out details which make up the lifeblood of the film. Patrice is a dear friend and collaborator and has lifted my dreams about cinema and life. I love setting sail with him at the beginning of a project because the sparks are real and it’s like jamming with someone who’s hearing the same melody. The excitement comes from knowing that he will push the song to unexpected heights and there’s no stopping until it’s real.” —Kickass Canadian Sam Hudecki, storyboard artist & concept designer (Enemy, Prisoners, Sicario, Arrival, Blade Runner 2049, Dune)

Nuts-and-bolts cinema

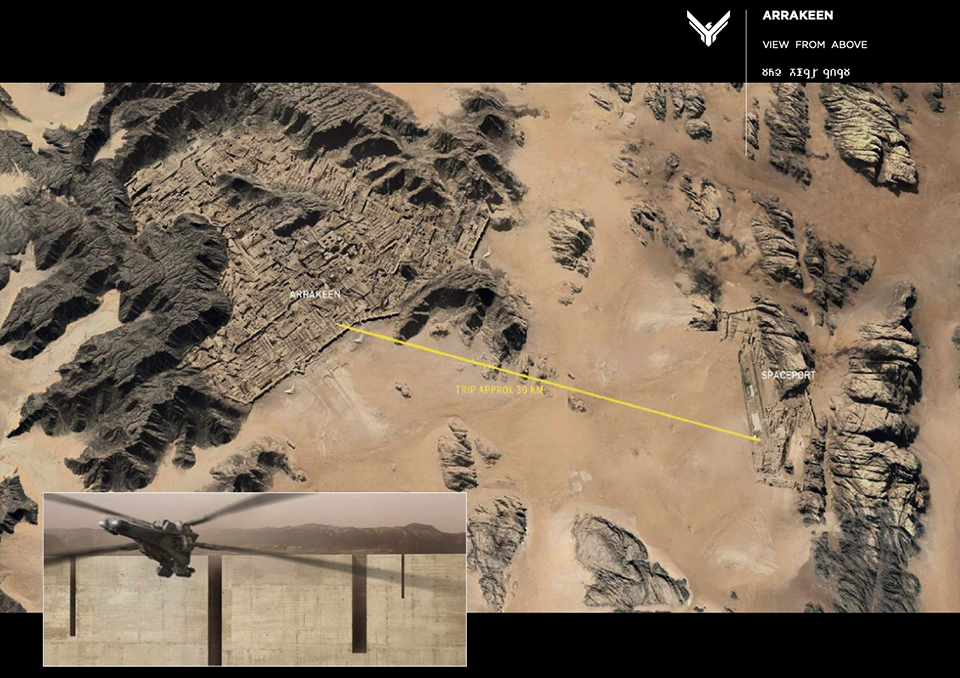

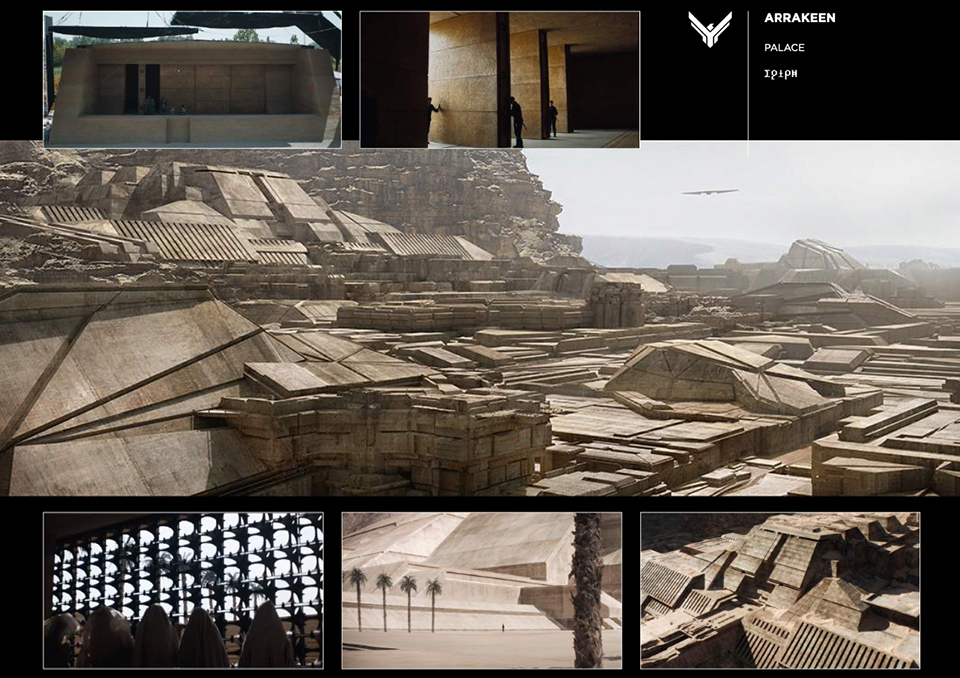

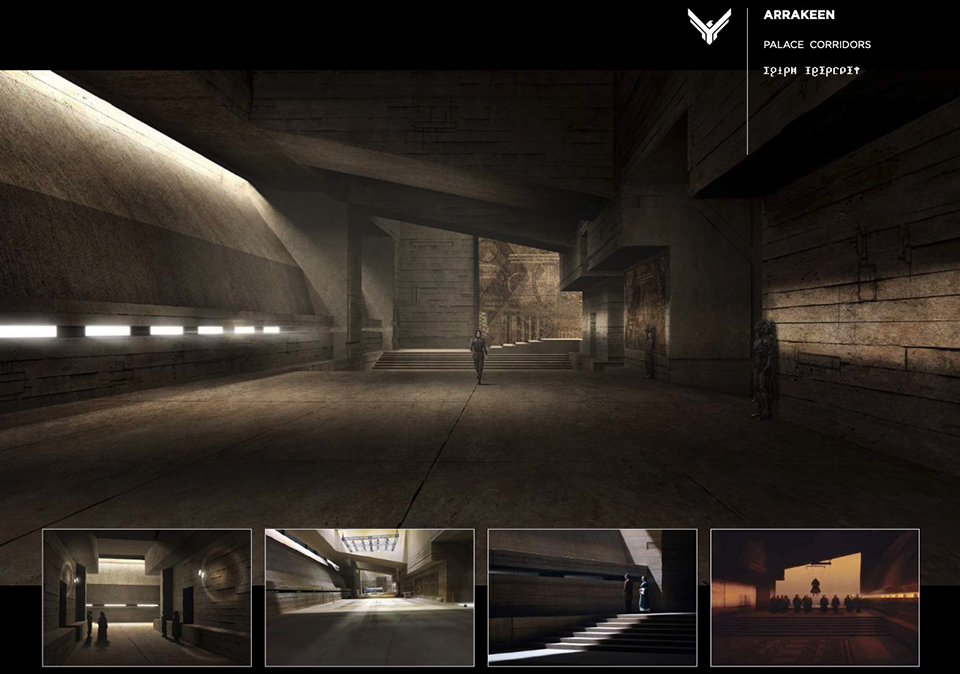

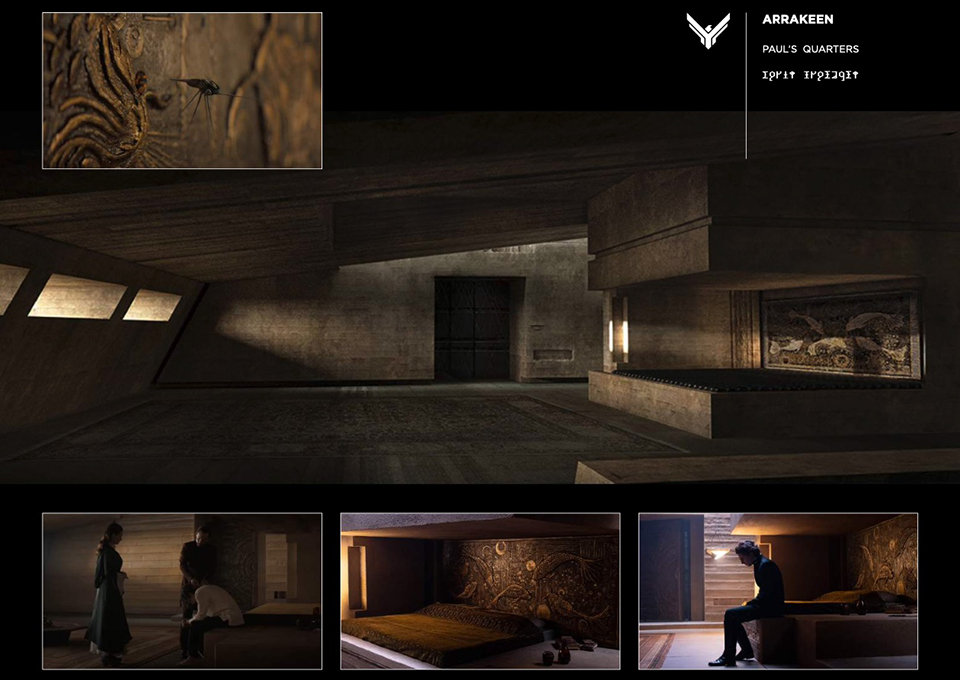

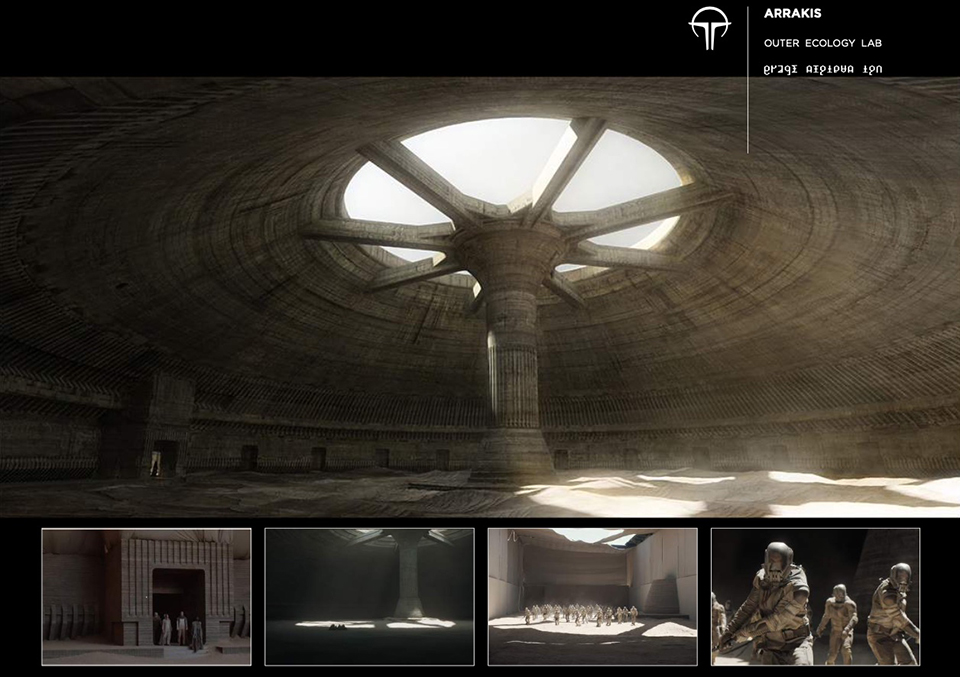

Consider Arrakeen, the capital city of the desert planet Arrakis: in designing the city and its palace, Patrice imagined himself in the position of the people who first established that city. “You have to go with the elements, which are in the book: it’s the wind at 850km/h, it’s a very hot planet—the sun can kill you—there’s the sandworms. So, you react to that like the founders of Arrakeen would have done.” That meant establishing the building in a natural protective environment (a rock bowl within mountains), designing the structure with sharp angles so the wind could sweep over it, and creating thick walls to contain cool air and shut out direct light.

Then there’s the Brutalist architecture, and the “immensity and scale of the sets, there to support [protagonist] Paul’s journey in a world that is bigger than he ever expected; his journey is way bigger than just being the son of a duke,” says Patrice. Also, to impose on the natural world, to show power over the local population, as “any colonial entity would want to do… Nothing is there just because it looks cool; it’s because there’s thought behind it.”

From “Dune”

From “Dune”

From “Dune”

From “Dune”

Patrice has accounts of this kind for every film he’s worked out. The common thread is that his designs exist to serve and elevate both the story and the production as a whole.

There’s the circular sets in Arrival. Also, the logograms—the aliens’ visual language. Denis, Patrice and Aaron developed 100 complete logograms for the movie, and engaged a linguist and a mathematician to analyze them and confirm that they conveyed an actual language. “It’s because we’re a bit crazy,” says Patrice. “We don’t want anything to be random.”

The logograms in “Arrival”

He also acknowledges the capacity he and his team share for being “super nerdy” and easily excited by a good problem-solving challenge.

For The Mountain Between Us, Patrice talked the producers out of relying only on natural settings, and designed a way for them to build the sets—including a lake, a forest, a house—so they could control their environment. “We found a field that was extremely flat in between a valley, had the right sun orientation; we created a fake lake; we planted thousands of trees… We did all that in the fall and then let nature do its great set-decorating job with snow, and the falling leaves, and everything blended naturally together… It looks like there’s no art direction but it’s full of art direction.”

That approach gave the crew better control over their production schedule, enabling them to film the mountain-top scenes, at 11,000 feet, on days when wind and visibility permitted, and left them free to film other scenes the rest of the time, on what was effectively a backlot that contained every other location within walking distance. At the end of the shoot, says Patrice, “the producers said, ‘Thank you for being crazy enough to suggest that.’”

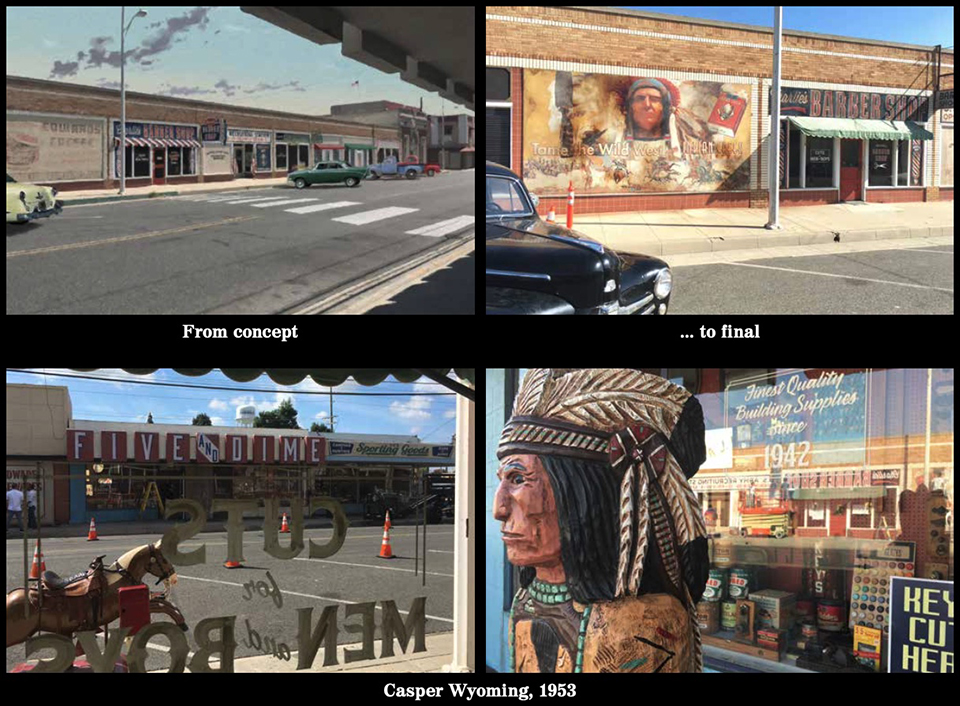

When Patrice spoke to me about Vice a few years ago, he outlined how he and the crew found creative ways to have California stand in for Afghanistan, Cambodia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Milan and Wyoming, among other places.

From “Vice”

From “Vice”

On Dune, for the scene in which Liet Kynes (Sharon Duncan-Brewster) leads Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) to Nexus, her secret botanical lab in the desert, the Budapest crew was challenged with creating a realistic shadow on the ground that would mimic the shadow cast by the digital set, to be added later in VFX—all without using green screen. “You can’t light that with studio light,” says Patrice. “You can’t compete with sunlight, which gives the perfect effect.” The lab is a cavernous dome with a massive pillar that reaches 360 feet high—much too big to be built onstage. To replicate its shadow, they created a partial set 30 feet high and added fabric to extend it to 65 feet, all in the right hue to reflect what the lab’s ambient colour would be. Then, factoring in the angle of the sun, they calculated what size the opening in the fabric needed to be to cast the right shadow to match the VFX. They also had to routinely groom the sand on the ground “because Budapest rains in the summer, like in Toronto or Montreal, so we had to cover our sand and rent agricultural equipment to turn over the sand every time it rained, to make sure there was no humidity on the sand, because on Arrakis there’s no humidity.”

Added to the mix was the studio’s orientation: the sunlight only hit the desired angle between 10:45am and 11:20am, giving them a 35-minute window to shoot that scene on any given day—and it had to be done when there wasn’t wind, so the fabric of their retractable ceiling wouldn’t blow and move the shadow. “That was an extreme team effort that took months to prepare. You need the producers to allow us to go to that extreme, you need a 1st assistant director to make a schedule with the possibility of shooting that… you need the cinematographer, director, VFX supervisor [Paul Lambert] all on the same page. It was such a complicated set-up that we all needed to watch other’s blind side, but it was crazy enough to work. And it did.”

From “Dune”

Patrice cites that multi-departmental collaboration as a classic example of production design being more than just design; it’s also at the service of the entire production. “It’s about analyzing the situation—every movie is a different situation—and asking, ‘How could my work help everyone else?’ It’s not just about creating your own department… it’s about seeing the production as a whole. It’s about finding solutions.”

“Production design and editing are, visually speaking, tag teams of the filmmaking process. Which normally means that when I join the film and meet up with Pat, I’m at my most wired and he is at his most Zen. That’s something I take enormous comfort from—the calm that comes from knowing Pat and Denis have already cracked it. Pat normally publishes a book of illustrations, which I pore over: glimpses of the world they’ve summoned. Creatively and conceptually, it has 100% coherence and a thrilling amount of depth. On Dune, I remember being struck by the concept images of the Arrakeen Palace—despite the volume, there’s a kind of heavy weight to the proportions that make it feel like a desert tomb. Sam’s storyboards help get me closer still. My task is to make sure it’s populated emotionally and has clear rhythm. Pat’s a drummer, so he appreciates that stuff. Living in the universe Pat and Denis have imagined has been one of the great joys in my life, and I pinch myself that I get to do it long before the general public.” —Joe Walker, editor (12 Years a Slave, Sicario, Arrival, Blade Runner 2049, Dune)

This is only the beginning

For the moment, Patrice is focused on finding solutions for Foe, as he prepares to complete prep for the shoot. He’s looking forward to reuniting with his family for the holidays, although it’s hard to imagine he won’t spend at least some of that time dreaming up ways to help bring Denis’ vision of Dune: Part Two to the rest of us.

I ask Patrice what gives him greatest fulfillment: working on films, watching the finished products or having audiences see them? “It’s a bit of everything, but it’s seeing how audiences connect with it. I think when you create something, you don’t create it for yourself—you create it for people to appreciate. That’s the best reward: if people connect with it, if you can touch people, it means mission accomplished. Art can be therapeutic but it’s also made to share and to be appreciated by other people; you hope other people appreciate it. It’s about the communion of ideas when you work on the project as a collaborative effort, and it’s about the communion of ideas with the spectator afterwards.”

If there were a mood board for his future, I imagine it would be full of images of all sorts of high-quality, yet-untold movies. The locations remain to be seen, but with Patrice’s fountain of creativity and extraordinary work ethic, there’s no limit to the places he’ll go, the worlds he’ll unveil to audiences.

“I’m lucky to be in a place where I can choose my projects and I just want to be doing my job right,” he says. “I want to be proud of the movies that I work on, and in the long run, hopefully those movies will stand the test of time… I’m a movie-lover and I like to be told stories and to be touched by those stories, first and foremost. That’s part of sharing my passion for making movies—it’s because I love being told stories. And I love the film format: there’s a beginning and an end.

“Unless there’s a Part Two.”

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians