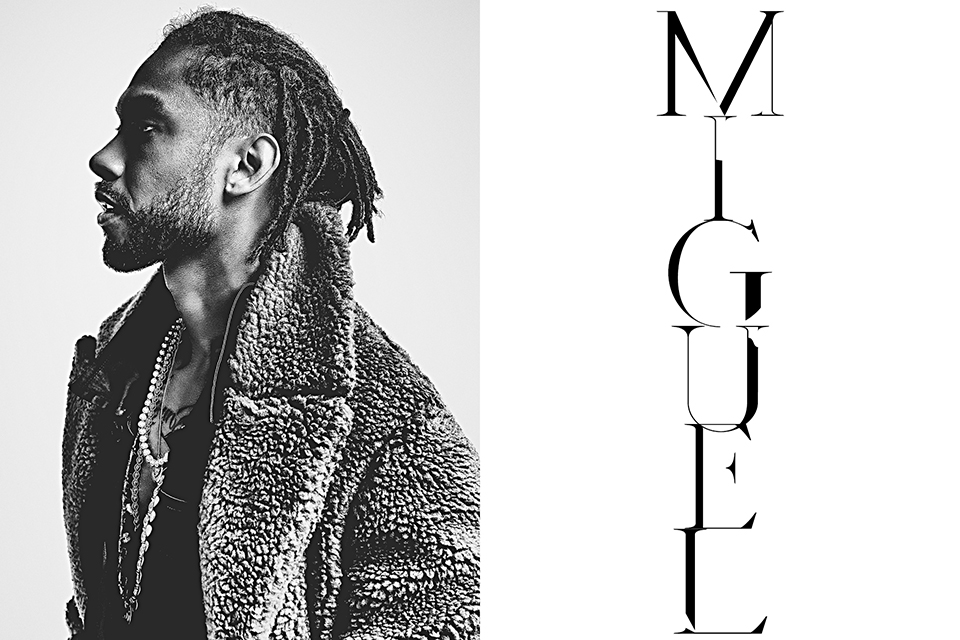

Richard Bernardin, photographer-storyteller

“It’s important as a photographer to try to celebrate as many different colours and shapes and sizes as possible. But it takes opportunity to do that. I want to explore different ways that I can use my talents to help create those opportunities.”

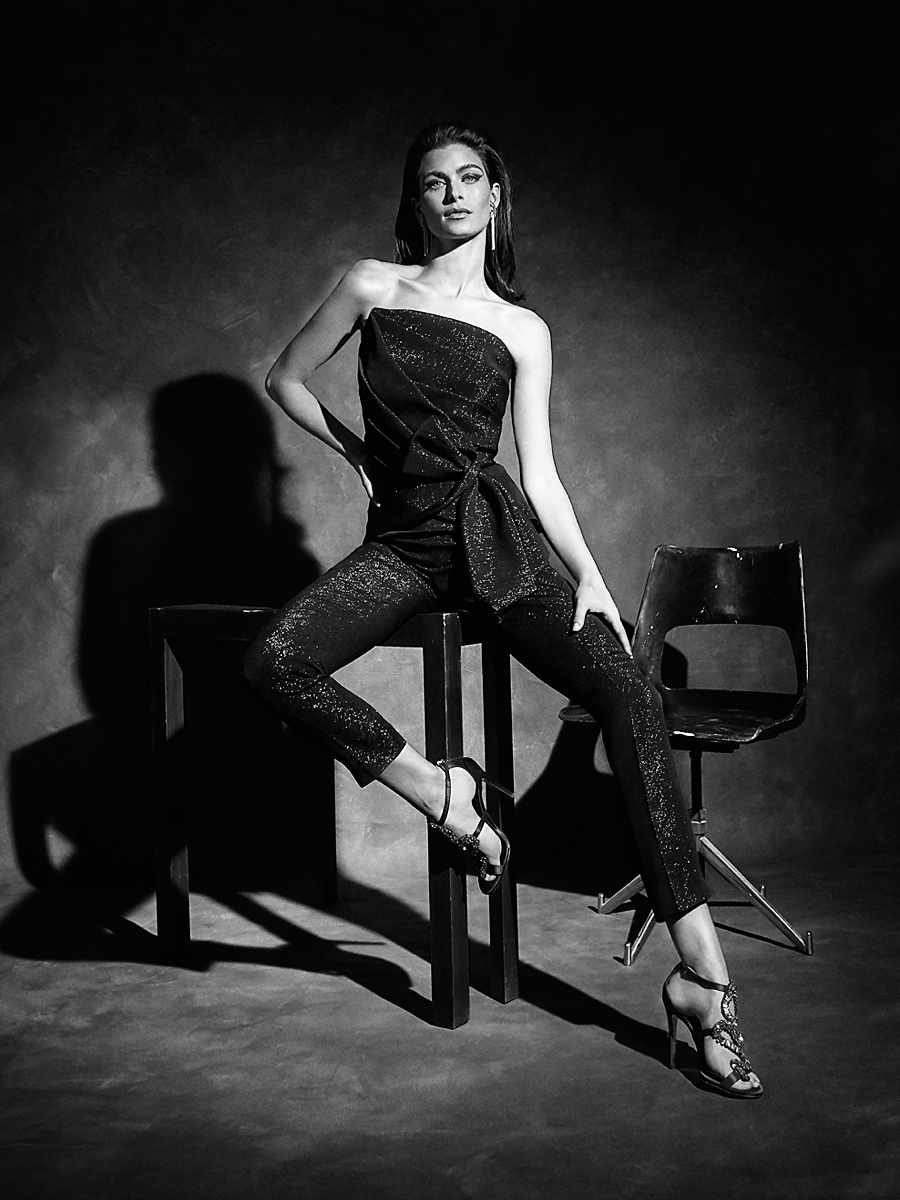

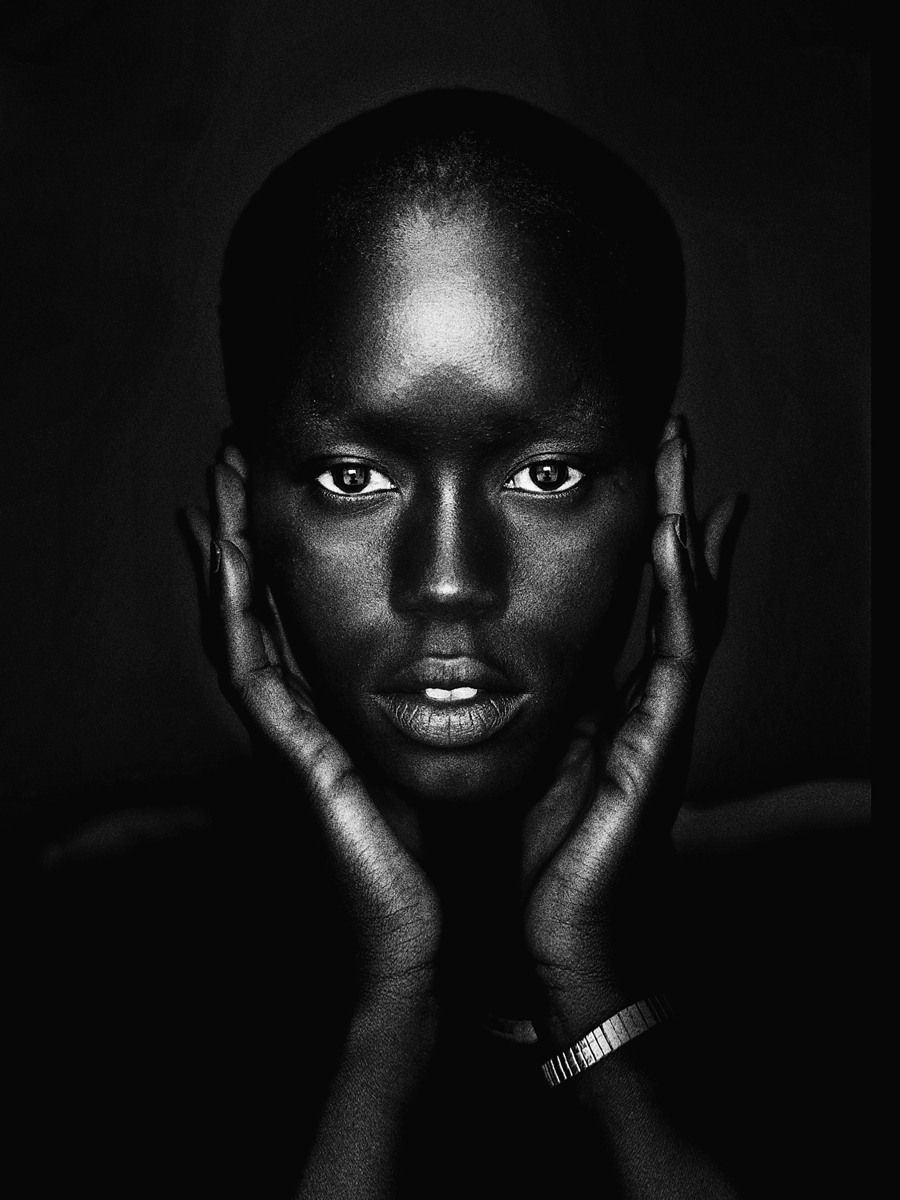

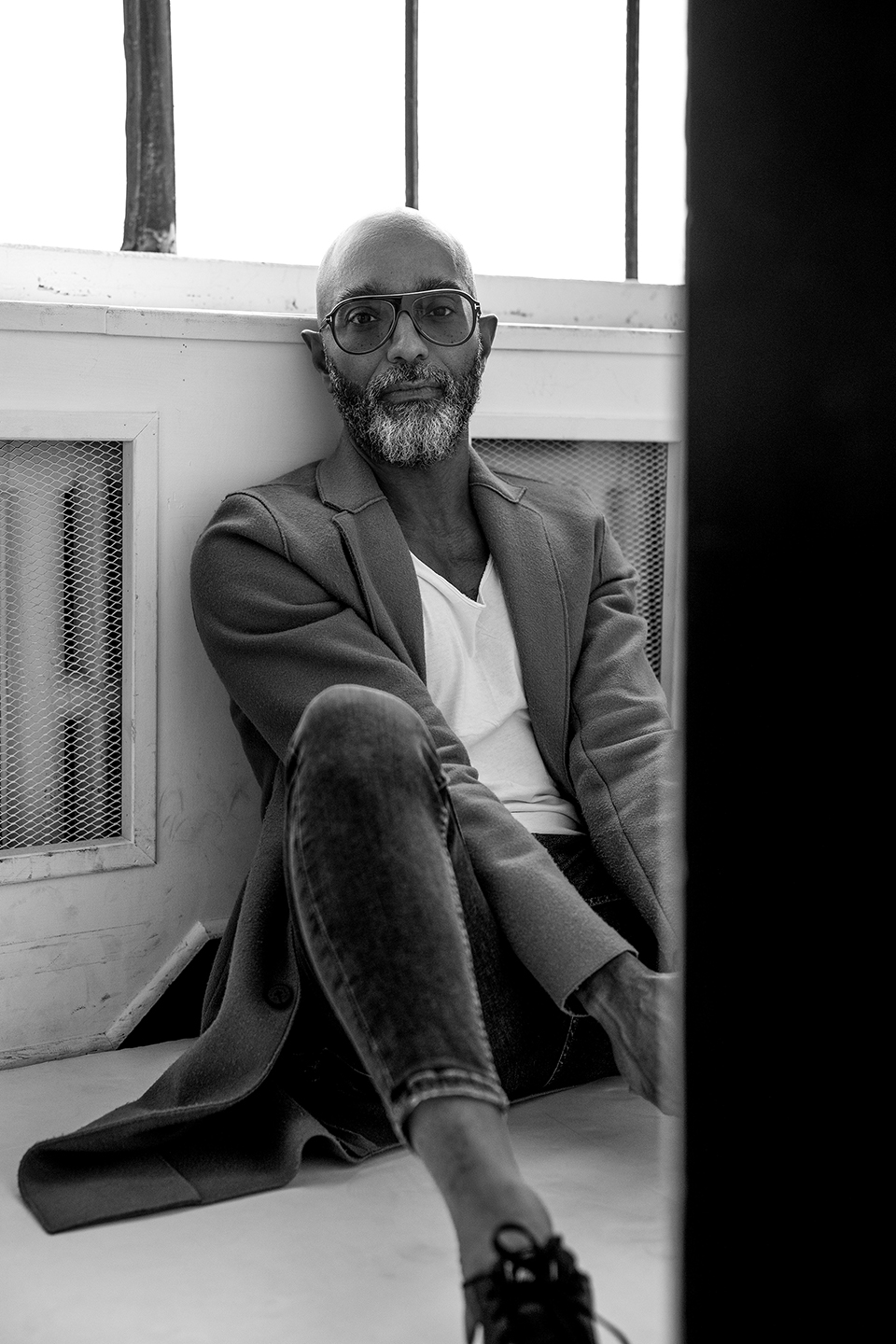

All photos by Richard Bernardin

Before becoming one of Canada’s most successful fashion photographers, before contemplating a career in filmmaking, before serving in the United States Marine Corps, Richard Bernardin wanted to be an architect. He loved the idea of creating structures that are strong enough to support and withstand, but that are also full of beauty, boldness and distinction. Configurations comprised of a variety of shapes and colours, all complementary yet unique.

Although he wound up pursuing another craft, he hasn’t abandoned his original dream: through his vision and focus, he has become an architect of change for the world. He’s helping to restructure and reimagine a new narrative—one that will hopefully be much more stable and supportive, as well as more colourful and beautiful.

Foundations

Richard spent most of his childhood and adolescence in Trois-Rivières, Quebec. But he was born in Chicago, Illinois, in the district where Barack Obama ran for office. (He still holds both American and Canadian citizenship, and is proud to have cast one of the votes that ushered in the country’s first African-American president.) His parents are of Haitian descent, and met in Chicago, where they’d both gone to study. When Richard arrived, they decided that Canada would provide the best quality of life for their children (a daughter and another son came after Richard). They started out in Toronto, Ontario before settling down in Trois-Rivières.

There, nestled between Quebec City and Montreal, Richard grew up reading and watching science fiction, and devouring comic books. He was—is—a self-described geek and even belonged to a sci-fi book club. (His “favourite movie of all-time” is Blade Runner, which was recently reimagined as Blade Runner 2049 by his fellow Kickass Canadian and former Trois-Rivières resident Denis Villeneuve, for whom Richard has “the deepest and utmost respect.” Denis also directed the upcoming Dune remake. “All the stuff that I loved when I was a kid is being made and remade into movies,” says Richard. “I am in paradise.”) He also spent a lot of time watching American TV. Shows like The Jeffersons, The Cosby Show and, later, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air provided much of his “overall perception of being a Black person living in Canada” in his youth. “I identified directly with the subject matter and the people onscreen.”

Particularly in the late 70s and early 80s, he says, there weren’t a lot of Black people in Trois-Rivières. Rather than living “the Black experience” that some of his family members had in the United States, he describes “a unique upbringing,” a very multicultural scene. He attended a small English-speaking school where the same group of people went through elementary and high school together. “All my friends were from a whole bunch of different races and countries from all over the planet—India, Pakistan, Norway, Haiti. Obviously, there were white Canadians, too, but we were such a small, tightly knit group that colour was never a subject of conversation. Not that I didn’t see (our differences), but it was no big deal. We went to birthday parties and one day it was our Chinese friend and we all went to his house and we made egg rolls. Every time you went to someone’s house, it was about celebrating where they’re from and embracing it.”

Those formative experiences shaped the outlook he currently brings to his professional life. “I wasn’t raised to emphasize or prioritize one race or one ethnic background,” he says. “So, in my work, I always photograph the people who are appropriate to the project we’re working toward. Black, male, skinny, plus-size—it doesn’t matter. For me, it’s always been about finding the person who best suits the project, no matter what race, shape or form.”

Illumination

Richard first started exploring photography in his early teens, although it wasn’t something he initially saw as a career goal. He played around with his father’s camera and joined the yearbook committee. But he still saw himself as an architect and, after graduating from Three Rivers High School in 1988, enrolled at Montreal’s Dawson College to study architecture through the Applied Science program. It proved to be an imprecise fit. The program included a mandatory chemistry class, which felt to him to be too disconnected from architecture. “Chemistry was a lost cause for me,” he says. “I didn’t understand it.”

During that time, he saw an ad for the Marines stating that the military would pay for university after service. Thinking he could ultimately study architecture at a university and concentrate on more trade-specific courses, he contacted the U.S. recruitment office and enlisted. That decision wound up pulling his career goals into sharp focus. Part of his work involved using photography for reconnaissance, and it reinforced his love of interpreting the world through a lens. “I’ve always been attracted to composition, light, structures and blocking,” he says. “That came rushing back to me during my time as a Marine.”

After finishing his service, he returned to Montreal and began studying photography at Dawson College. He lasted a few weeks. “The whole structure of learning in that context—of actually sitting in a classroom rather than being out in the world—was not something I could do anymore.” So he spent a year in New York City learning the craft in real-world settings, including interning under fashion photography greats such as Michael Thompson, Mario Testino, Robert Klein and Richard Avedon.

When he moved back to Montreal, he was left wondering how to incorporate his love of film and storytelling into a career. He’d become passionate about photography, but what he cherished most was the concept of creating a narrative—of telling a story through images. Many of his friends were studying film, and although the idea of becoming a film director appealed, he saw the frustrations and limitations his peers were grappling with. “This was the early 90s, pre-Internet, pre-digital,” he says. “There was no way you could finance a film on your own back then. Renting the equipment, buying and processing the film, was cost-prohibitive.” He didn’t want to be restricted by those barriers; he was ready to start his career. But he wasn’t about to give up on his love of storytelling. “I realized I could shoot two rolls of film and create a story through photography rather than spending thousands of dollars on a film. I could still have that narrative thread but shoot it with a still camera, using a film style.”

He started out doing experimental photography and holding exhibits. When his partner (now his wife) became pregnant with their first of two sons, he decided it was time to stop the “feast or famine” cycle he’d been living as an artist. Knowing that the cinematic aspect of photography was what he most wanted to capture, he identified two possible avenues for his career: photo journalism or fashion and advertising. “What I appreciate with photo journalism is that you’re capturing moments that you cannot script, which is amazing. But I had stories I wanted to tell… Fashion and advertising was the answer. I could use the signature that I had developed, in a way that was commercially viable yet still creatively fulfilling.”

Raw exposure

Richard’s approach has led to a phenomenal career. His work has appeared in various international editions of ELLE, Vogue, Grazia and Rolling Stone, and his subjects have included Meghan Markle, Freida Pinto, Xavier Dolan, Dita Von Teese, Adam Cohen, Jessica Paré, Nelly Furtado, Ashley Graham and Hailey Bieber. By any standard, he is a highly successful photographer. And although he was aware of the dearth of Black photographers on set—as well as Black stylists, makeup artists, art directors—he never imagined that the colour of his skin was holding him back. Then, Black Lives Matter was launched.

In the wake of that movement, Richard got a call from a photographer friend. A couple years earlier, his friend had been shooting for a major American fashion brand and they’d asked to see Richard’s portfolio. They loved the photographs and set up a meeting, but after seeing him in person they told him it wasn’t going to work out. At the time, Richard didn’t think anything of it. But over the phone, his friend said that the client’s verdict was that Richard “doesn’t necessarily fit the brand image of our photographers and our team,” and implied that his race was the reason he didn’t get the job. “Until then, I never thought that I lost work because I was Black,” he says. “I’d never considered that.”

Not that he felt immune to the effects of racism. As a Black person, he’d grown accustomed to “a certain amount of racism that you’re subjected to on a daily basis.” He gives two examples: being stopped several times a year on his commute into downtown Montreal and asked whether he owns the high-end vehicle he drives; and noticing women crossing to the opposite side of the street when he’s walking his dog. “I’m not imposing; I’m 5’8” and slim and 48 years old,” he says. “When people say there’s no such thing as systemic racism, there is. Here and abroad. It’s different in Canada than in the United States—it’s more insidious here, it’s more hidden—but it’s still present. Does it stop me from being an optimistic person, loving life and loving what I do, and having great friendships and great opportunities in my work? No, it doesn’t. But it happens. It’s part of life.”

This summer, in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canon Canada invited Richard to become one of their ambassadors. As a result of that partnership and the need to promote himself online to compensate for pandemic restrictions—in addition to revived focus on Black Lives Matter—he’s begun presenting himself on social media in a whole new way.

“Do I see myself as being a Black man? Yes. Do I sell myself as being a Black man? Until this year, never before. I sold myself as a photographer. But after learning that my colour may have hindered me in the past, I’ll gladly add that distinction: I’m not just a photographer, I am a Black fashion celebrity photographer. If in doing so I can open more doors for myself and other people, I’ll celebrate it and I’ll take the win.”

Black Lives (Still) Matter

When the Black Lives Matter movement began in 2013, Richard says it didn’t immediately have a direct impact on him. “We’re all connected, through the Internet, TV,” he says. “Even I became desensitized to the fact that every single week, we were hearing stories of mass shootings in the United States and Black people being wrongly shot for reasons a white person wouldn’t. It became commonplace until it crystalized, right after the (pandemic) confinement began this past spring, with George Floyd. When I saw that video… it profoundly disturbed me. I cried. I was hurt watching that video.”

He recalls conversations over the past few years in which people have said to him that Black lives matter but other lives matter, too. “Sure,” he says, “there are people of all races and nationalities who have suffered or are in financial need. There is suffering on all levels but very few people so much as Black people, especially in North America, have had the fear of being judged and being segregated and being persecuted solely because of the way they look.”

By the time he watched the video of George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, Richard was overwhelmed by one thought: “This has to stop.”

That was the impetus to return his attention to a project he’d had on the back burner for several years: a portrait book that honours Black Lives Matter by celebrating great Black people. “Growing up, I had all these Black people I looked up to, from (celebrities), to my father, my uncle—a large variety of people that I love and respect as Black people,” he says. This summer, he started a wish list of subjects, including prominent politicians and performers, as well as some of Richard’s family members and personal friends. “I want to shoot each person’s portrait and give them the opportunity to say what it means to them to be Black now.”

Canon Canada is committed to helping him realize his vision, with the hope that in 2021 it will be easier to travel and photograph. “My goal is to inspire a whole generation of people who think that workplaces like film and fashion and sports don’t have opportunities for them,” he says. “They do. From (athletes to actors), there are beautiful, strong Black people doing all kinds of work and succeeding. It’s amazing what they’re doing. If I can find a way to bring them all together and inspire, that’s the whole point.”

Now more than ever, Richard is dedicated to using his art and photography to empower others—particularly Black people—to achieve their goals. “Obviously, it’s important as a photographer to try to celebrate as many different colours and shapes and sizes as possible. But it takes opportunity to do that. I want to explore different ways that I can use my talents to help create those opportunities.”

* * *

In addition to the Black Lives Matter portrait book and his commercial work, Richard is currently working on a compilation book of his fashion photography and is writing two short films, which he hopes to shoot in 2021. He’s also designing his dream home, to be built just outside Montreal, in collaboration with Ottawa, Ontario architect Mélina Craig (another Trois-Rivières treasure and the person who nominated Richard as a Kickass Canadian—merci beaucoup!).

For the latest on Richard, please visit his website, and follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Very impressive, Richard. We’re very proud of you. I was going to say it’s surprising how many TRHS graduates have excelled in their chosen domains, but, thinking back, we had a pretty incredible environment. Good luck with your new projects. Kick some ass out there.

Salut, j’avais acheté de Galerie SAS une superbe photo en noir et blanc, d’une nue en pause dans un appartement de Habitat 67. J’adore ce que tu fais. Please reach out.