Susan Benson, designer-painter

“You’re trying to create a visual world that the audience can believe in.”

Susan Benson is one of Canada’s premier designers for theatre, opera and ballet, and one of the country’s most gifted and imaginative painters. She was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1986. Her paintings and designs are featured in collections far and wide, including the Portrait Gallery of Canada, Stratford Shakespeare Festival and National Arts Centre (NAC), as well as the Bronfman Collection at the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Yet if you ask this exceptional woman about her outstanding success, she’ll say in her soft-spoken way that she is still shy and insecure, just as she was in her childhood. “It doesn’t matter how much you accomplish,” says Susan. “If (that insecurity) is there, you always question yourself.”

Not that she feels her disposition has been a hindrance. As an introvert, she often stood back and observed others, acquiring a keen sense of awareness at a young age. From her perspective, it’s better to be a bit insecure than overconfident, particularly as an artist. “I think you’ve got to be very careful if you have an ego. You’re not necessarily as sensitive to other people and to what’s going on around you.”

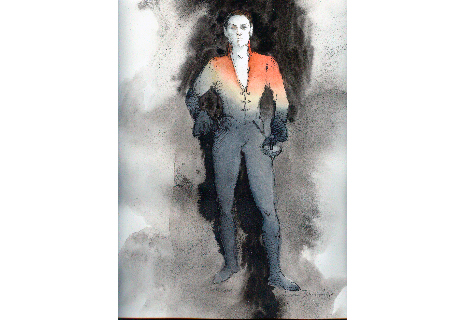

Death in Venice, Canadian Opera Company

When I first met Susan more than a decade ago, her sensitivity to others was very clear. A family friend, she took me to lunch at the NAC to answer some questions I had about working in theatre. She didn’t hesitate to take time from her exceedingly busy schedule to share her considerable wisdom.

Over the years, I’ve often heard of her remarkable accomplishments, and seen programs from the performances she designed. She has long been in the background of my life as an amazing example of talent, dedication and accomplishment.

But for anyone actively involved in the world of stage, Susan is much more than a background player. She’s a bona fide star.

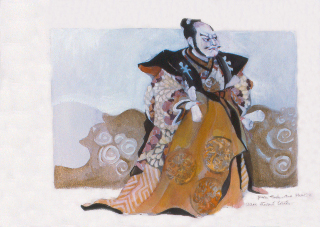

The Mikado, Stratford Shakespeare Festival

Stage mother, grandmother, father

Growing up in Kent, England, young Susan was surrounded by art.

Her mother and grandmother were heavily involved in theatre, and both acted in some of Alfred Hitchcock’s last silent films. Susan’s grandmother Maude Weavings earned recognition under the stage name Barbara Verne. Although passionate about acting, Susan’s mother Jane eventually shifted her focus to become more active as a theatre director, and a writer for stage and radio. Susan’s father John, whose main profession was optometry, did a lot of writing for prominent British comedians.

“Theatre was part of my life,” says Susan.

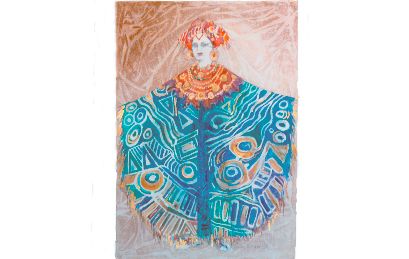

The Ballad of Baby Doe, San Francisco Opera

As early as seven years of age, she started designing costumes and sets for herself. She entered her work in competitions organized by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). When she was 12, she began designing for her mother’s shows.

“I was lucky because (my family) encouraged me,” says Susan. “There was never a moment when I was made to think it was a silly thing to do… They praised what I was doing, and I think with any child, that helps them to progress along the lines that they are interested in.”

An artful education

With her family’s encouragement, Susan began studying her craft more formally. She attended a number of art schools, and also took acting lessons at her mother’s theatre school.

“I think (studying acting) helped me as a designer because it makes you more aware of the human spirit and the human condition, which is what acting’s about, really,” she says. “It was invaluable to have that acting background as a designer in the theatre.”

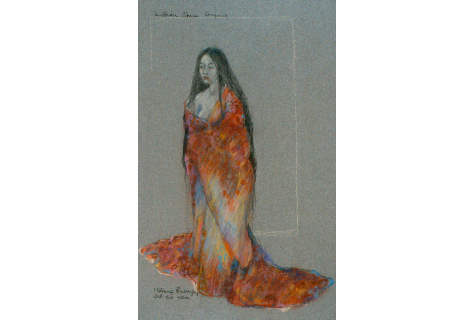

Madame Butterfly, Canadian Opera Company

After graduating from Bristol’s West of England College of Art (now the University of the West of England), she found work in the wardrobe departments of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and BBC Television. As Susan sees it, working her way from the ground up was the best thing that could have happened to her.

“I learned my craft, in a sense, by sewing costumes, and dressing and observing,” she says. “I wasn’t designing there, but I was learning to do that ground work… That’s important because (designing) is not just drawing pretty pictures, which I think a lot of people think it’s all about.”

Death in Venice, Canadian Opera Company

Canada-bound

After a few years as a professional in her field, Susan and her family—including her parents, grandmother and younger brother Jonathan—decided to emigrate to Canada. It was 1966, and the Canadian government had advertised in Britain that they were welcoming immigrants with professional backgrounds and training. Every member of Susan’s family fit that bill, so they relocated to Vancouver, British Columbia.

The family was in for a bit of a letdown when they arrived. They’d ensured that their professional qualifications would be recognized by the federal government, but didn’t realize that the provincial government used its own standards. For Susan’s father, who had worked as an optometrist with Britain’s National Health Service for 30 years, the matter posed some serious problems.

“We got out to B.C. and they turned to my father and said he couldn’t practice,” says Susan. “That’s happening today for many professionals. They don’t tell you you’ll have to go and retrain (when you arrive)… It’s all very well and good to decentralize things, but it doesn’t help to get people working.”

Lighting the stage

Once the Bensons got their feet back under them, things started picking up. Susan found work designing for a number of theatres, including the Vancouver Playhouse.

Through her work, she met lighting designer Michael Whitfield, whom she married in 1971. The two became a formidable force in the international arts scene, often collaborating on plays, operas and ballets. Both have designed for the Canadian Opera Company (COC), National Ballet of Canada, Royal Winnipeg Ballet (RWB) and San Francisco Opera (SFO).

The Golden Ass, Canadian Opera Company

Susan has also designed for the New York City Opera and Opera Australia, and has taught set and costume design at many educational institutions, including the National Theatre School of Canada (NTS). In addition, she spent four years designing and teaching at the University of Illinois’ Krannert Center for the Performing Arts.

Stratford Shakespeare Festival

The artistic contribution for which Susan and Michael are best known is probably their work in Stratford, Ontario, where they now live. Michael spent several years as a resident lighting designer for the Stratford Shakespeare Festival. From 1974 until her retirement in 2005, Susan designed sets and costumes for dozens of the company’s productions, and spent several years as head of design. Her résumé, which is long and deeply impressive, includes Cabaret, Julius Caesar, A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Macbeth, Guys and Dolls and The Crucible.

Cabaret, Stratford Shakespeare Festival

Susan has countless fond memories of her time at Stratford. One that stands out is her experience designing for director Robin Phillips’ production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1976. “That was the year Jessica Tandy played Titania and Hippolyta,” says Susan.

Another cherished memory was working with director Brian MacDonald on The Mikado. That production ran at Stratford from 1982 to 1984, and was brought back again in 1993. It was remounted in 1986 for an American tour.

The Mikado (Palanquin Bearers), Stratford Shakespeare Festival

“The Mikado toured more than any other show from Stratford,” she says. “It was incredibly well received… and was of tremendous public relations value to the festival.”

The Mikado (Pish Tush), Stratford Shakespeare Festival

Susan takes great pleasure in seeing her designs succeed. But what she loved most about her work was the combination of having quiet time to dream up her own creations, and getting to merge her talents with those of the many other team members on each production.

“The part… that was mine, in a sense, was actually putting (designs) down on paper, or creating the set models,” she says. “That stage of (the process) I particularly loved. But it’s also the collaboration with many different people—artists, directors, actors, wardrobe cutters, fabric painters, prop people, set builders and so on. All of those people are artists in their own right, and it was that collaboration that I enjoyed.”

Master class

Susan is truly a master of her craft. In addition to being elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, she has received eight Dora Mavor Moore Awards, as well as a Jessie Richardson Theatre Award and the 2001 Canadian Institute of Theatre Technology Professional Achievement Award. Her designs were selected to represent Canada five times at the Prague Quadrennial, which exhibits the work of theatre designers from around the world. In 2000, she was awarded the Banff Centre National Arts Award for her contribution to the arts in Canada.

Her words of wisdom to aspiring designers are these: “Get a good training. Learn your craft. Don’t try to go too far, too fast. And be flexible in your work and in your approach.”

H.M.S. Pinafore, Stratford Shakespeare Festival

She points out that she designed for a range of venues, and explored theatre, ballet and opera. She also became an accomplished painter, which she says “keeps your mind fresh in the way you observe and look at things.”

Such varied experience helped ensure that she produced inventive, original work throughout her entire career, and didn’t get stuck in old habits. She cautions that designers are just as subject to typecasting as are actors; without a concerted effort to stretch one’s creative muscles, there is a risk of falling flat.

Art by design

There was very little risk of Susan’s work ever falling flat. Though officially retired, she still gets commissions to paint portraits. And she continues to receive awards for her outstanding contribution to the arts in Canada.

In November 2010, the Canadian Actors’ Equity Association made her the recipient of its Honorary Membership in Equity. The award was particularly meaningful to her, because she always made a point of putting the performer ahead of everything else—including her sets and costumes. From Susan’s perspective, her job was to provide a springboard for the actors that would enhance and enable their performances. It wasn’t to draw attention to her own work.

“You’re trying to create a visual world that the audience can believe in,” she says. “You want to give focus to the piece, and I think that, more than anything else, for me (the focus) was always the performer.”

Romeo and Juliet (Tybalt), National Ballet of Canada

As it turns out, Susan was right: that ability she developed in childhood, to stand back and observe others, has served her well. Such sensitivity and awareness enabled her to hone in on the essence of each piece she turned her hand to.

Rather than drawing focus to her designs, Susan devoted herself to bettering the work of others through her creations. In doing so, she left the pleasure of admiring her beautiful designs entirely to the rest of us. What a gift.

* * *

For more on Susan’s incredible career and art, visit susanbensonart.com. You can reach her at [email protected].

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

That’s one talented lady. Love the artwork.

You said it, Matt! I’m in awe of her creations.