Teva Harrison, artist-writer-cartoonist-student of nature-beam of light

Hear the latest podcast with this Kickass CanadianRecorded: January 7, 2020

“Use your time and use it well, for what matters most to you.”

Dearest Teva passed away on April 28, 2019 at age 42. She shone light in the face of dark odds, living more than five years with metastatic breast cancer—five brilliant years that beamed with creativity, positivity, adventure and love. I’d like to share the words of Teva’s husband, David P. Leonard, taken from his post the day after Teva passed: “Her great joy was the kindness that people show, and the magic evident in the everyday bits of living. She was a pure beating heart. Carry magic with you. Hold people close. The world needs it.”

* * *

I owe the Ottawa International Writers Festival a debt of gratitude for introducing me to Teva Harrison. She was there this April, speaking on a panel called All My Life to Live, led by CBC’s marvellous Lucy van Oldenbarneveld. I went to see Kickass Canadian Bif Naked, but I had a feeling about the woman sharing the headline with her, that something special was coming my way in the form of Teva.

Now I know why. At the event, Teva proved to be a composed and compelling speaker, a gifted writer and, as The Globe and Mail describes her on its list of 16 Torontonians to watch in 2016, a “beam of light.” She is also grace personified.

Take it from Bif: “Teva is incredible!! She is such a wonderful girl, a heart-opening writer and a beautifully whimsical illustrator. Further, she moves, inspires and delights me with her unparalleled brilliance, her peerless illustrative style and her endless heart. Her thoughtful honesty is tragically beautiful, and meeting and getting to know Teva, even in a small way, is enriching and completely serendipitous. She is a treasure. I’m better for having met Teva.”

Bif and Teva at the Ottawa International Writers Festival, April 2016; Photo: David Leonard

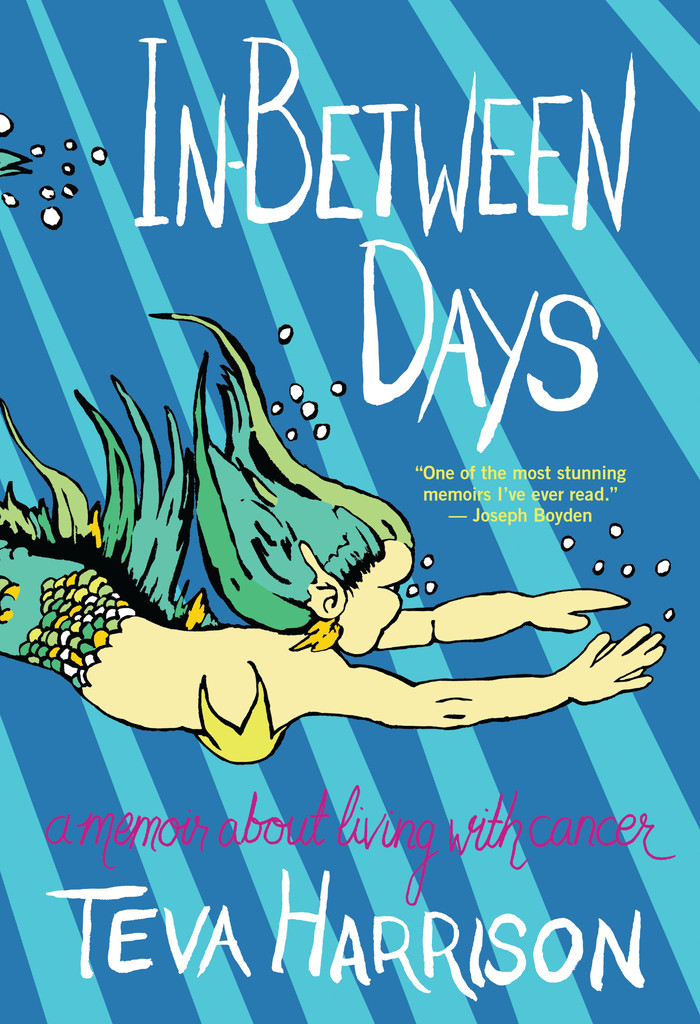

Teva was at the Writers Fest to promote her book In-Between Days, which Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden calls “one of the most stunning memoirs I’ve ever read.” It was listed in 49th Shelf’s Most Anticipated: Our Spring 2016 Non-Fiction Preview and made the Canadian Nonfiction list for bestselling books in Canada shortly after its release.

In-Between Days is a graphic novel featuring Teva’s drawings and short essays, chronicling her life both before and after being diagnosed with incurable metastatic breast cancer in 2013, at age 37. It’s moving, insightful, fanciful, serious, funny, beautiful and real. Her honesty spills over everything she writes about, from sex after abrupt-onset menopause due to surgery, to the moral dilemma of being a vegetarian who accepts cancer treatments tested on animals, to her fear of disappearing right in front of us—of getting lost in the in-between as she spars valiantly with cancer.

But the book is more than a cancer story. It’s also Teva’s story, herstory, imparting wondrous recollections of her family, her childhood and the breathtaking love she continues to share with her husband, The Walrus events director David Leonard. Her optimism and obvious joy are remarkable and amazing, and they ignite the desire to do more, create more.

So, in tribute to her powerful, wonderful book, here is a collection of short essays inspired by reading and talking to Teva.

In the garden of her mind, where ideas take root and soar skyward

When Teva speaks, it’s clear she is a born storyteller. Her words come out in prose, poetic and already shaped into a narrative—one that elicits strong visuals.

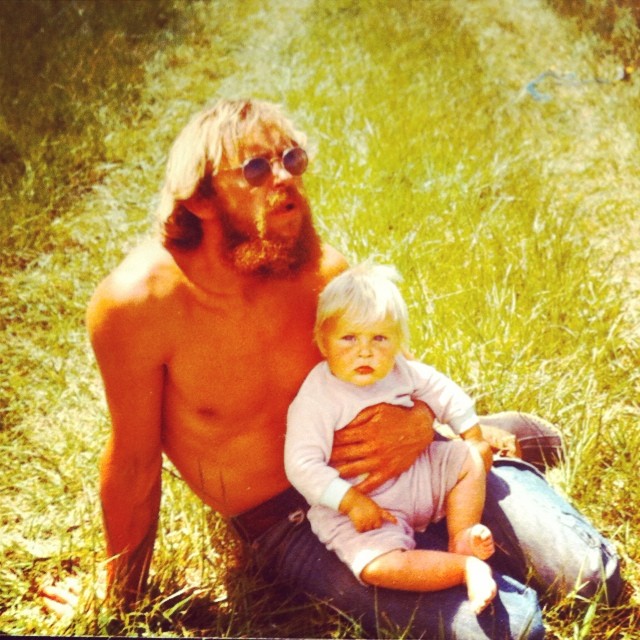

For instance: “I have a memory of sitting in my father’s lap and I remember feeling the scratchiness of his beard. It’s kind of one of those fuzzy snapshot memories, like a Gerhard Richter painting where you can’t quite focus.”

Teva with her father, Larry Harrison

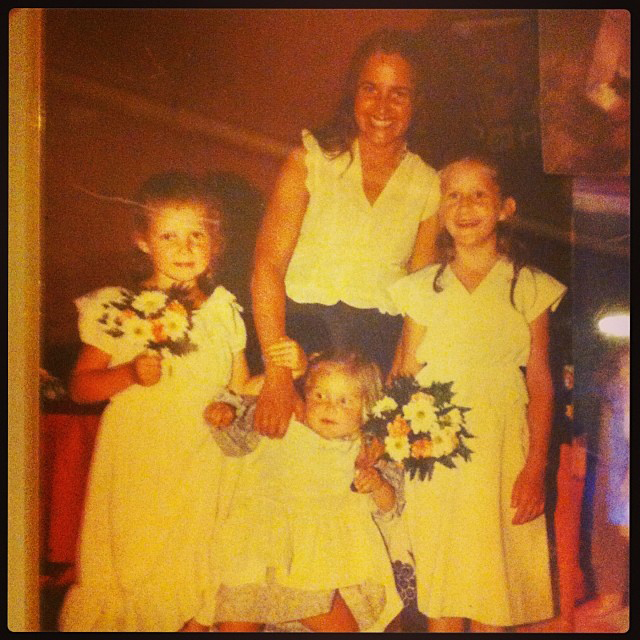

That memory is unique, and vague, because it’s one of very few she has of her father, who passed away when she was two years old. She and her elder sisters, Malu and Keira, were raised mainly by their mother, Teri, making for a highly collaborative household where “everyone pitched in; if you cooked, you cooked enough for everyone.”

With her mother and elder sisters at a family wedding

Two things were fundamental to Teva’s upbringing. First, there was nature—good, unstructured, outdoor fun. Growing up in Williams, Oregon, “we played in the forest, we played in the ditches,” says Teva. “We would walk to the general store or sometimes ride our horses there. There was a hitching post in front of the general store when I was a kid; it was that rural. We had a place called Greyback Brushriders down the road from my house and they did western riding contests there, so the summers were all punctuated by the announcer’s voice, announcing people doing all the different elements of western riding, calf roping and log sawing.”

There were also questions—constant questions. “Questioning is inherent to being a Jew,” she says. “We’re raised with the idea that questioning is the basis of discovery, of learning and intellectualizing and connecting, and reaching some sort of understanding with the people in your life.”

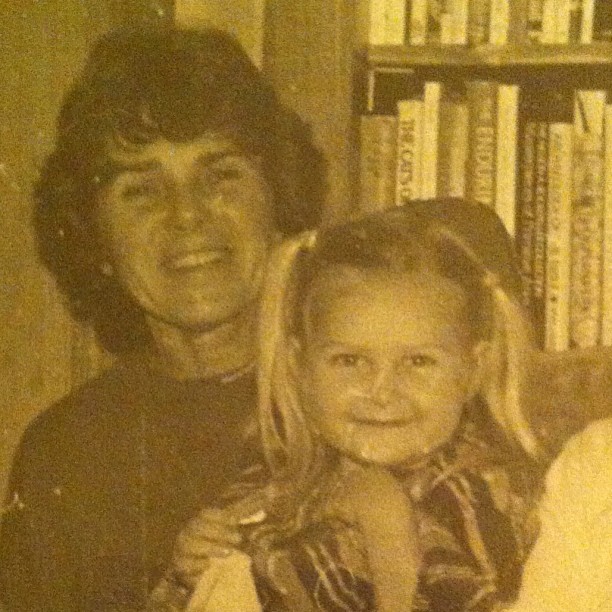

That pervasive curiosity was nurtured greatly by Teva’s maternal grandmother, Ruth Levin March (whom Teva documents beautifully in the essay in her book called “Granny’s Legacy”). “I had a really beautiful dichotomy in my childhood between growing up in deep nature and having grandparents in Los Angeles,” says Teva. “My grandmother was really worried that, growing up in small towns, we’d grow up with small minds. So, she’d take us one at a time to different places. It started in the U.S. to learn American history, and then to wherever we wanted—we got to choose.”

Teva and her granny, Ruth Levin March

Her granny didn’t reserve learning for big trips. Every outing was an opportunity for discovery. At Indian restaurants, Ruth asked to take the children into the kitchen to see “how they made bread in the special oven.” When they flew, in the days before airplane security, she brought them to the cockpit to meet the pilots and see how things worked. “That level of access, and that idea that often all you had to do was ask and you could learn, I think is one of the hugest gifts she could have given me,” says Teva.

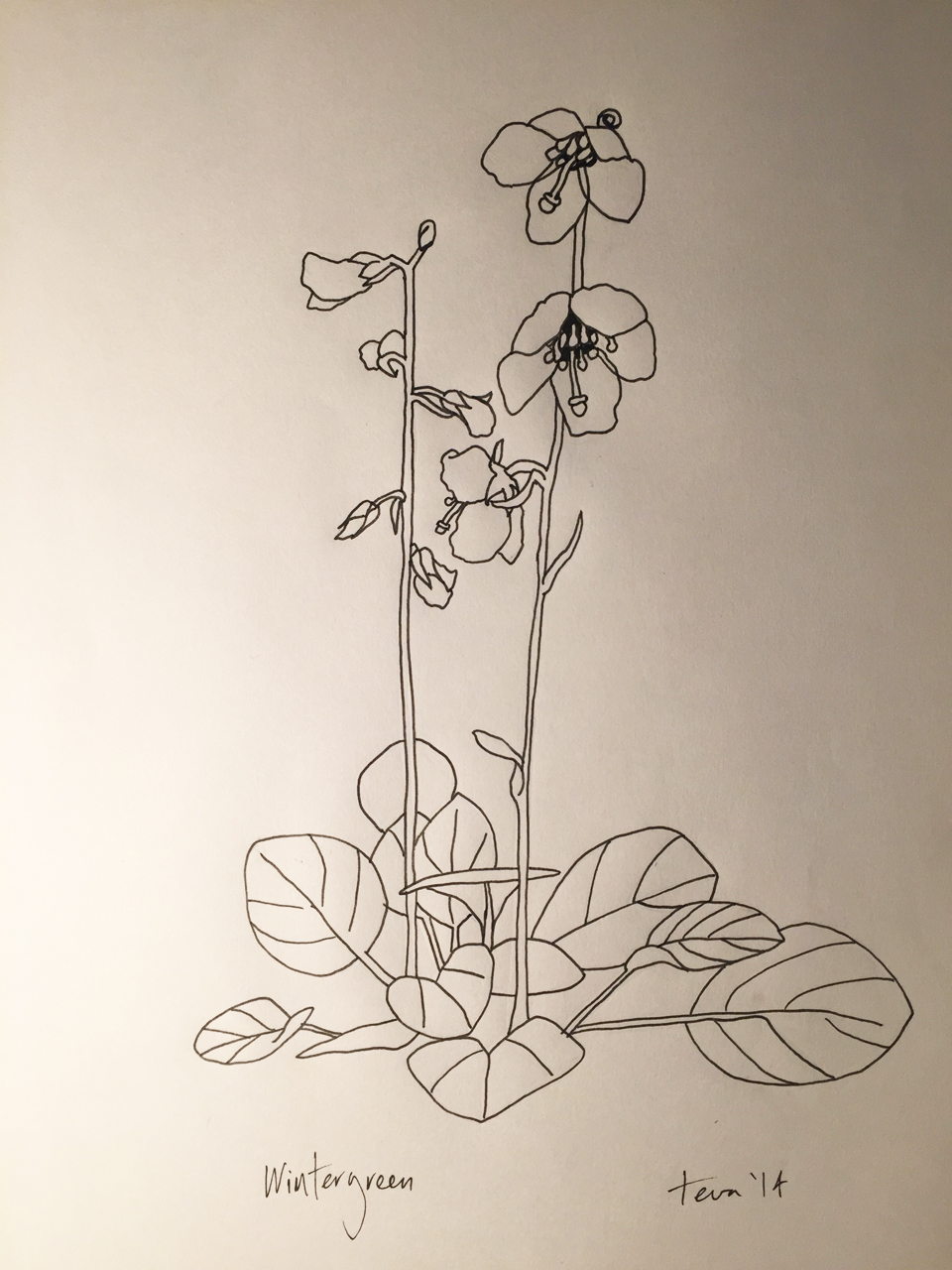

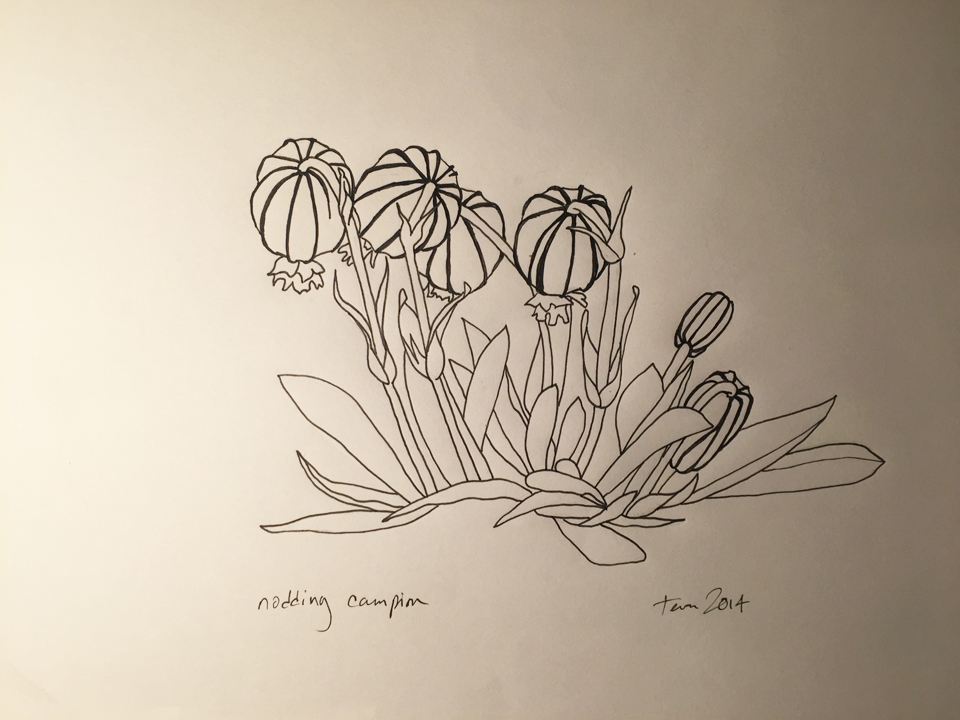

In high school, in Grants Pass, Oregon, Teva’s keen mind and eagerness to learn led her through an assortment of independent studies, after she “tore through” the offered academics. There was a reading conference in women’s studies with her advanced placement English teacher, studio art class with her art teacher, and “my advanced biology teacher gave me the keys to the greenhouse, where he was growing all these different, interesting plants that aren’t available in the wild in southern Oregon. So, I would go in on my break to the greenhouse and draw exotic plants… I’ve had so many interesting opportunities.”

During her junior year at Hidden Valley High School, she studied half the time at her local community college, after having successfully petitioned the high school for the right. For her senior year, she transferred to Grants Pass High School in the city so she could take more Advanced Placement classes.

After graduating high school in 1994, she moved on to Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, alma mater to the likes of cartoonists Matt Groening and Lynda Barry. “That was an incredible place,” she says. “That experience of going to a school that focused on multidisciplinary courses that maybe crossed something from the arts and something from the sciences, and different combinations that really supported each other—I think that really helps one to think that way, when they go on in life, to think about what happens when X and Y become greater combined.”

So, from Williams to Olympia and everywhere in between, the seeds of creativity continued to mix and mingle, sprouting ideas, musings and insights, all watered regularly by the imagination and intellect growing rampant in Teva’s fertile mind.

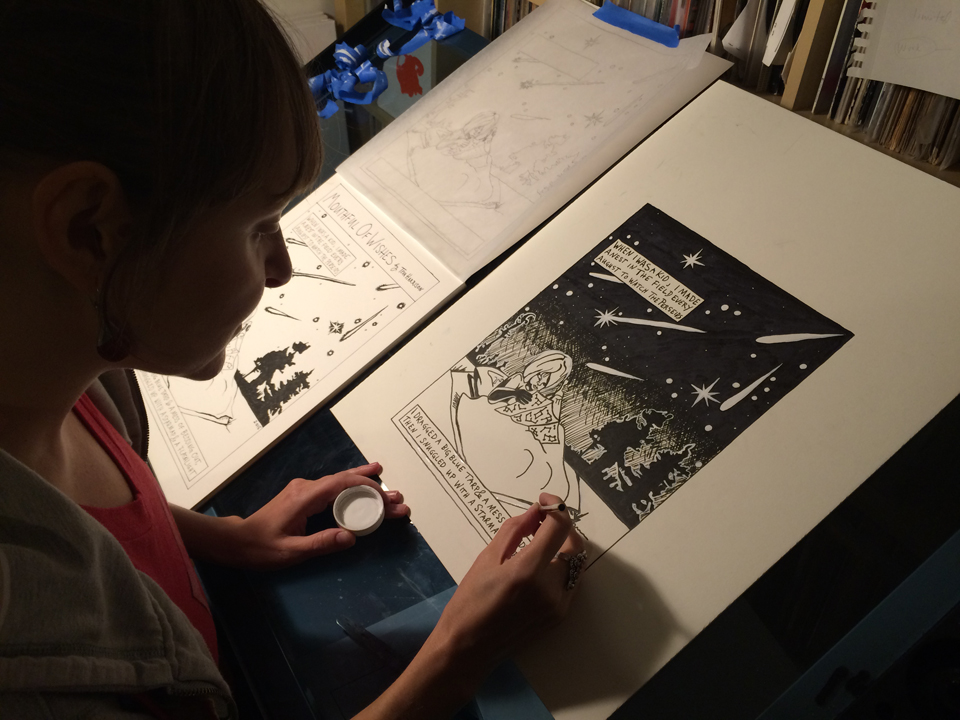

Illustrating “In-Between Days,” Photo: Malu Wilkinson

She said “Yes” – to love and life

Teva’s career fell into place quite organically, starting with a job as program director for the Olympia Film Society, which came about after she’d volunteered for the organization while studying at Evergreen. That position led to work with the Seattle Poetry Festival, the inaugural Ladyfest, and various “little spots of work” for other music events, art shows and festivals.

All appeared to her as opportunities that were too good to pass up. She took them because, in her words, “I’m a person who has always said ‘Yes’ a lot.”

So of course she said yes when she found herself stranded in Toronto, Ontario in September 2001, out dancing to try and forget the terror of the world beyond—that prevented her from travelling to New York City, as planned—and staring straight into the bright blue eyes of a boy with “eyelashes for miles.”

Teva and David fell in love that first night and have been together ever since. In 2002, she moved to Toronto, where she took a job at Quill & Quire and a husband, David. (She became a Canadian citizen in 2013.)

“David is tremendously good company,” she says. “I’m very, very lucky because I think he’s exceptionally, especially good company for me. We love so many of the same things, so it’s very easy for us to agree. He brought a kind of calm into my life that has been so comfortable. We have fun and there’s excitement but there’s also a kind of peacefulness. It took me awhile to get used to such a healthy way of interacting.”

When David officially proposed, just months after their meeting, Teva managed a breathless, “Yes.” Then they both collapsed in tears of joy and relief, each the other’s greatest treasure, finally theirs to have and hold.

Teva and David at dinner just after eloping, Toronto, Ont., 2002

To be seen and not to be seen (in the places in-between)

As Teva tells it, cancer changes perceptions. It changes the way others see the patients, and the way they see themselves.

When her cancer was discovered in late 2013, she was told that the median survival was two to three years from diagnosis. “Statistics mean nothing on an individual basis,” she says. “But there hasn’t been a marked improvement in survivability of Stage 4 breast cancer in many, many, many years.”

So far, two-and-a-half years in, she is heartily prepared to defy the statistics. Still, there has been a heavy cost. She had to step down as director of marketing at the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC), a place she’d worked at since 2008 and was heartbroken to leave. And she and David had to give up on their hopes of having children, something Teva struggled to let go.

Teva and David at the Nature Conservancy of Canada gala

For the past 18 months, she’s been part of a clinical trial at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, which has allowed her to keep some semblance of a normal life. But her days have been transformed in practically every way, a far cry from the long, über-productive hours she used to log regularly.

Now, in between hospital trips, her days might involve working in her garden, doing some drawing, getting outside for a walk or to see friends, and always trying to remember to eat properly. “I don’t have much of an appetite,” she says. “The drugs I’m on currently really suppress it and I think there’s also something to do with the cancer, too. So, I set timers reminding me to eat.”

Those are the good days. On a bad day, she often has trouble making it to the kitchen to find food. “I probably won’t have the energy to prepare anything very exciting, and I’ll probably spend most of that day in bed drifting in and out of sleep,” she says. “It might be a day where I’ve had a lot of pain so I’ve had to take more pain medication, so I’m a little vague. It might be a day where I’m just really tired; some days the fatigue is really deep. If I’m in really bad shape, like if I can’t make it downstairs, I call a friend and they’ll come help me.”

Before she got sick, Teva had a mental image of herself. It was the portrait of someone who had real confidence in herself, in what she did and who she was. Post-diagnosis, she could no longer introduce herself as director of marketing at NCC; suddenly, she wasn’t sure how to introduce herself at all.

“I didn’t like the idea of introducing myself just as a cancer patient,” she says. “We are all more than what we’re treated for or what we do, but I was feeling really lost and I was very much in between.”

That feeling was exacerbated by spending so much time in liminal places—waiting rooms, doctors’ offices, hallways, blood labs and pharmacies. “There was so much waiting,” she says. “I was in so many spaces in between, neither here nor there, not quite in a destination, not quite home. And I had entered into the in-between space between living and the end, whenever that might be. I mean, I guess all of life is the space in between birth and death, but mine just got a little bit truncated.”

Clearly changed but without a clear idea of what she was moving forward to, Teva lost sight of who she was. And it wasn’t made any easier by what others seemed to see.

Because of her treatment plan, she appears to be quite well. She still has all her hair, still looks like a healthy woman approaching 40. But that appearance belies the severity of her illness.

“The thing about looking normal is funny, because (my condition is actually) more serious than that of many (cancer patients) who look worse,” she says. “People find out that I’m sick and they say, ‘Oh, but you look so beautiful, you look so well; you must be better now.’ It’s like it just does not compute.

“When I’m out in the world, if I’m having a rough day, if I still have to go the hospital even though I really should stay in bed, sometimes I’ll take a cab or an Uber because I can’t face taking the subway and looking the way I do but not knowing if I’ll be able to find a seat. Because I feel really guilty asking for one. I feel like people look at me and they see me as I look, not as I am.”

Small wonders in a harsh landscape

Cancer runs in Teva’s family. On her maternal side, her great-grandfather died of leukemia at age 43. Her grandmother, great-aunt and aunt all had reproductive cancers that first struck when they were in their 30s.

When Teva was diagnosed in 2013, she looked for a book that addressed what it really feels like for someone her age to live with cancer. But all she could find were starkly clinical books for people twice her age, or books for children.

That desire to find a book that could help cancer patients like her, coupled with her newfound “leisure” time in which to create, led to a blog she launched in February 2015 to post her comics about cancer. The comics were promptly migrated to The Walrus, which recognized the appeal her comics would have for others, and that exposure attracted House of Anansi Press, which saw the potential to transform her posts into a book.

All of that has led to a smattering of opportunities, including leading a memoir workshop at NorthWords Writers Festival, being interviewed by Kickass Canadian Shelagh Rogers on CBC’s The Next Chapter, writing for The Globe and Mail, and being featured in variety of renowned magazines, including Maclean’s, Chatelaine and Quill & Quire.

In Yellowknife for NorthWords, June 2016; Photo: Lawrence Hill

Teva is also putting the finishing touches on her next publication for Anansi, The Joyful Living Colouring Book. Due out in November 2016, the colouring book for grownups features “a combination of things that make me happy,” she says. “It has things ranging from things that just make me giggle, like a couple dinosaurs eating cake as volcanoes explode behind them, to images of nature, of flowers or animals, or images or people doing things really joyfully. It’s motivated in part by the work I’ve done with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy since I got sick. Colouring books are a tremendous mindfulness tool and I’m hoping that it will bring people some peace and joy.”

She couldn’t have known what was to come, but these opportunities are a direct result of her cancer—of having to take a step back, of being forced to leave her job. “When I was at NCC, I didn’t have a lot of my own time, so I wasn’t really doing a lot of drawing, I wasn’t really making a lot of art,” she says. “Then I got sick and I went through a couple months where I was really depressed and just watched a lot of Netflix. But then I started painting.”

The painting was an unexpected side effect of something that happened shortly before her diagnosis—when the cancer was already in her bones but she didn’t yet know it. She went as a representative of NCC on an Adventure Canada trip to the Northwest Passage, exploring Greenland into upper Nunavut. “It was amazing,” she says. “We were moving too quickly for me to do a lot of sketches, because we wanted to see as much as we could, so I took a lot of photographs on the trip.

“After my diagnosis, I pulled up all these pictures I had taken of Arctic flowers, and they’re so beautiful and small and they were the most surprising thing to me about the tundra. I had been expecting ice and I was expecting rocks, and some of the wildlife we saw. But I wasn’t expecting this tundra covered in wildflowers, and all these colours, and they were so tiny and so beautiful. So, I just started drawing them.”

It felt right, at a cellular level. So, she kept going, and from those first few strokes, darkness morphed into even more unexpected beauty and good. Because vision, creation, kindness and inspiration also run in Teva’s family.

From left: Teva’s cousin Tova, Teva, her sister Keira, mother Teri and sister Malu

But I would give anything

And yet.

“I’m kind of torn,” says Teva. “This is all so cool… I should always have been making art. I should always have been. I get caught up in things, I get excited, especially when there’s a good cause to work on, and I do the thing I’m doing very intently. And so, I was doing other things—and they were all valuable, I don’t want to discount them. But I am happier when I’m drawing. I’m a better person, I think, because it brings me to my purpose.

“It does feel really good to quite suddenly have shifted to being, in many ways, doing the things I always should have been doing—making art and writing and sharing and talking—and I love that I got to lead a workshop at NorthWords about telling your own stories and how to bring those stories to the surface, because I think that’s such a valuable thing. And I’m loving drawing comics, which is something I didn’t plan to do. I’m really glad to know that this is how I react to something like this—that my reaction is to fight to get the most I can out of what I have left.

“If only it wasn’t all happening because I have cancer… I’ve had such lovely opportunities come out of this, but honestly, I would trade it all to be healthy. I would.”

On “The Agenda” with Steve Paikin; Photo: Laura Meyer

Her message to others is simple: Use your time, seize your opportunities. Because you really never know.

“I was 37,” she says. “I was trying to get pregnant with my wonderful husband, I had a really great job. My life was fantastic, it seemed. And now I have Stage 4 terminal cancer, out of nowhere.

“People often ask me, ‘Doesn’t it bother you when people complain, just about the weather?’ That doesn’t bother me at all. What bothers me is when people waste time. Especially people who have some gorgeous talent they could be contributing, whether it’s business acumen or scientific inquiry or creativity, art, anything—community organization. We have an opportunity to contribute to the sum of human knowledge and experience, and yet we also have Netflix and it’s so easy to slip into not doing with your spare time.

“Use your time and use it well, for what matters most to you.”

At Lake Louise, Alta.

Natural wonder: Gros Morne, giraffes and obvious (if unexpected) magic

In descriptions of Teva, the word “magical” comes up a lot. If you know her, even just a little bit, it’s easy to see why; she’s cloaked in it, can’t help but leave a dusting of joy, light and love over everything she touches.

Take it from Shelagh Rogers: “Teva to me is the most magic mermaid of them all. My most cherished time with her so far has been in Hawaii on the Big Island. We met up at the beach, sun bathed, and went swimming. Teva just knew that the dolphins would join us, and an hour later, they did. We swam with the dolphins for about two hours. I really and truly believe that they were drawn to Teva. She sends out love and the dolphins received it on their radar. OK. Does that sound wacky? Not to me. I have seen her cast lovespells on people and animals. You know you are in the presence of love, of kindness. She says she wasn’t always this way. But now she is. And she has a trademark on the term ‘such love.’ And by the way, she makes me laugh my ass off.”

On the Big Island of Hawaii: Teva (centre) with Shelagh (second from right) and their families

Teva says her mother encouraged a “strong sense of magic” in all her children, rearing them to believe in whatever fancies they imagined. “It made her the happiest when we came to her with strange stories of magic and fairies in the forest,” says Teva. “It was delightful to her.”

There’s a chapter in Teva’s book called “The Dead Bird” that recounts the time she found a dead songbird by the side the road. Young Teva was bewitched by “the roughness of its skin, the smooth symmetry of its feathers, the dull glass of its inert eyes.” By the unexpected magic of such a close encounter with the natural world, of a creature’s vulnerability and of her power to protect its dignity, even in death.

No surprise, then, that she continues to find magic and rebirth in nature. In September 2014, she joined Young Adult Cancer Canada to climb the mountain in Newfoundland and Labrador’s Gros Morne National Park. The expedition was incredibly life affirming and empowering.

“Building up to that, I had been really not very able,” she says. “I was doing palliative radiation for my bone metastases, but my back was really bad and I had trouble lifting things. I wasn’t very strong and I had to have some surgery, so I was recovering from that.”

Still, Teva prepared to take the trip. She had a backup plan: a friend was coming along in case she needed help carrying her bag. But by the time September came around, she’d healed from surgery, the radiation had significantly minimized the pain in her bones, and she’d found a “super-light backpack” at Mountain Equipment Co-op that placed most of the bag’s weight on her hips instead of her back (“They were really helpful!”).

“In the end, I was able to carry my own things,” she says. “That feeling of climbing a mountain completely under my own strength—my body, my ability—which was so much greater than it had been for such a long time, that was hugely, hugely empowering. Climbing a literal mountain, not just a figurative one but a literal mountain, it’s powerful. It does something to your sense of self, and to your sense of what’s possible—and at that time I had been feeling like not much was possible. So it was a tremendous help in getting me back up to my natural optimistic self.”

Teva (second from right) atop the mountain in Gros Morne National Park with the Young Adult Cancer Canada group, September 2014

This July, Teva and David will embark on another wilderness adventure. They’re planning a trip that has long been at the top of Teva’s bucket list: to South Africa and Kruger National Park.

Teva says she’s excited to see all the animals on the wildlife reserve. “I’m going to have to try to not squeal the whole time because probably the animals don’t like it.” But there is one animal in particular she can’t wait to behold. “Since I was a little girl, I’ve always wanted to see giraffes in the wild. I know we’re going to see a million giraffes—they’re not the hardest thing to see in Africa. But that image of them, that graceful, awkward lope across the savannah, has always captivated me.”

In Teva’s chapter on the dead songbird, she mentions crystals as a sort of “obvious” magic. To me, they fall into the same category as chakras and spirit animals and the like. So, I’m curious; I look up the meaning of giraffe as a totem animal.

The giraffe reveals her secrets easily: they are clear to see, readily apparent. She stands tall and proud, a survivor, able to reach for sustenance and nourishment in places others cannot find it. She has higher perception, heightened awareness. She is long-reaching and far-seeing.

And, like Teva, the giraffe goes forward with grace.

* * *

For more on Teva, visit tevaharrison.com and check out her comics on The Walrus.

You can order In-Between Days from House of Anansi Press.

Kickass Canadians

Kickass Canadians

Amanda, this is a beautiful profile of this exceptional woman. Thank you. I felt as though I was in her company as I read it.

You do such fabulous work, you KAC.

Shelagh xo

Shelagh, that’s about the highest compliment you could bestow! So glad you felt I captured her properly. Teva deserves that, at the very least. Thank YOU, my Kickass friend.